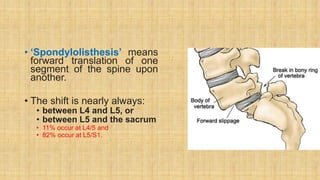

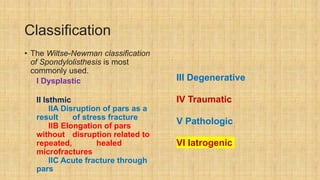

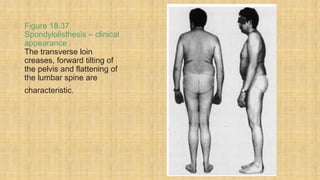

Spondylolisthesis is the forward slippage of one vertebra over another and most commonly occurs between L4-L5 or L5-S1. It can be caused by developmental abnormalities, stress fractures of the pars interarticularis, degeneration of the disc and facets, trauma or tumors. Symptoms include lower back pain and sciatica. Conservative treatment involves rest and bracing while surgery is indicated for progressive, high grade or neurologically compressive slips. Surgical options include fusion with or without instrumentation to reduce the slip and decompress the nerves.