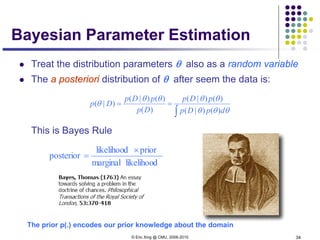

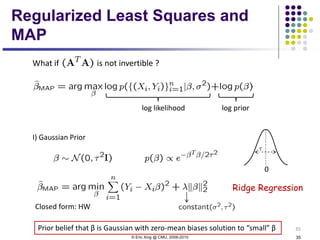

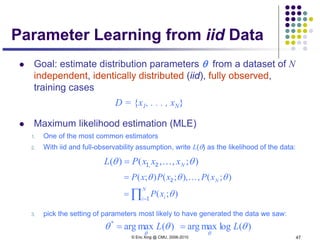

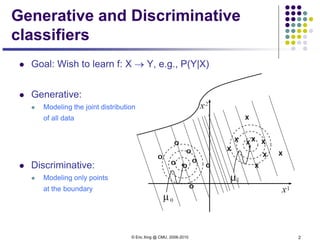

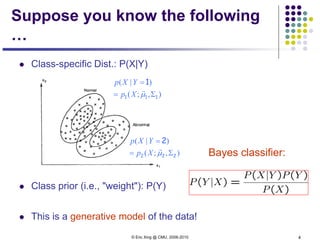

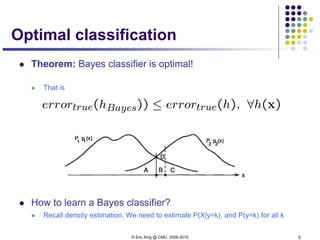

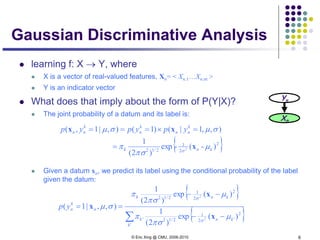

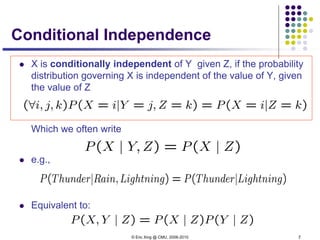

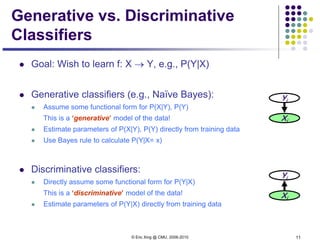

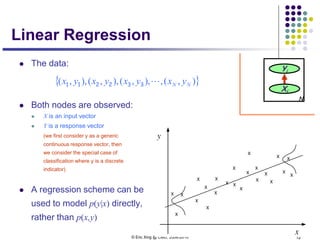

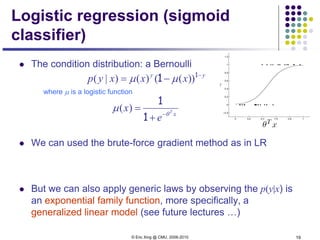

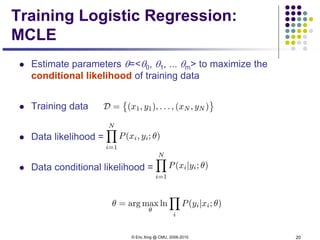

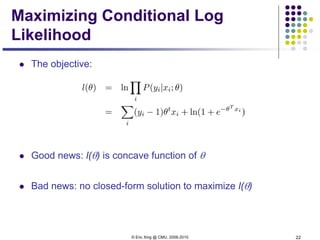

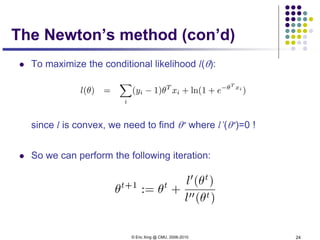

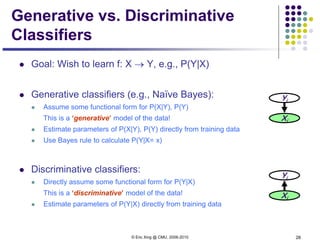

This document discusses generative and discriminative classifiers. Generative classifiers model the joint distribution of data and labels, while discriminative classifiers directly model the conditional probability of labels given data. Naive Bayes is an example of a generative classifier, while logistic regression is a discriminative classifier that directly models the probability of a label given input features. The document provides mathematical details on naive Bayes, logistic regression, and how logistic regression can be trained to maximize conditional likelihood through gradient descent.

![© Eric Xing @ CMU, 2006-2010 9

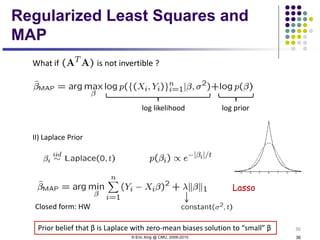

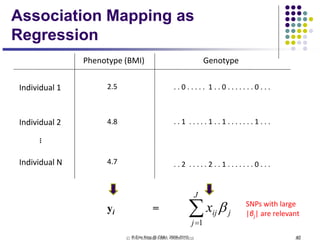

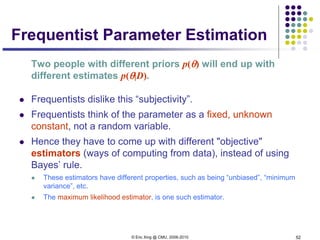

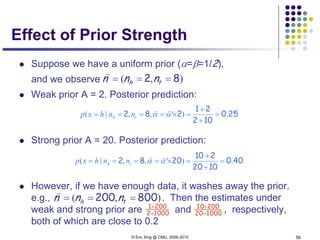

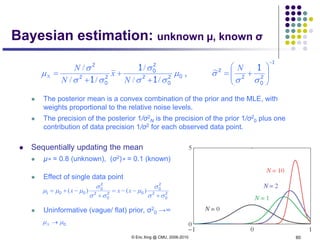

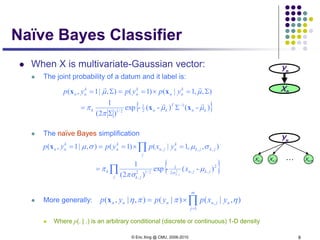

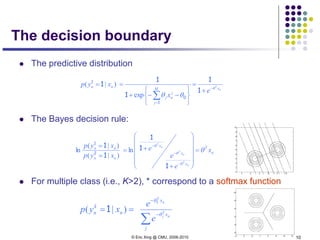

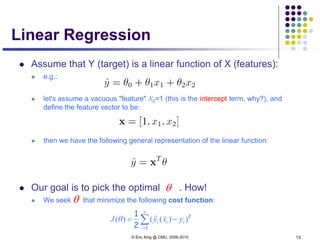

The predictive distribution

Understanding the predictive distribution

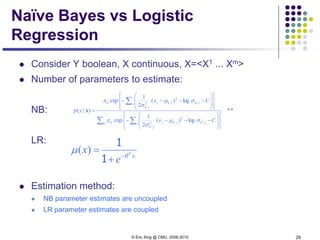

Under naïve Bayes assumption:

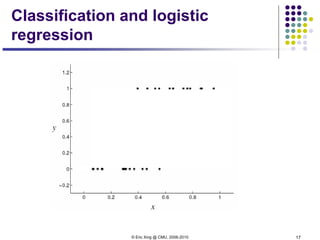

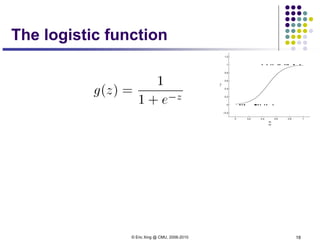

For two class (i.e., K=2), and when the two classes haves the same

variance, ** turns out to be a logistic function

*

),|,(

),|,(

),|(

),,|,(

),,,|(

' '''∑ Σ

Σ

=

Σ

Σ=

=Σ=

k kknk

kknk

n

n

k

n

n

k

n

xN

xN

xp

xyp

xyp

µπ

µπ

µ

πµ

πµ

1

1

( ){ }1

1

222

122

1

1

2

222

1

2

12

21

1

21

1

1

1

1

1

π

π

σσσµπ

σµπ

µµµµ

σ

σ

)(2

log)-(exp

log)-(exp

log)][-]([)-(exp −

−−−

−−−

++−+

=

∑

∑

+

=

∑j

jjjjj

nCx

Cx

jj

j j

jj

n

j

j j

jj

n

j

x

n

T

x

e θ−

+

=

1

1

)|( nn xyp 11

=

**

log)(exp

log)(exp

),,,|(

' ,''

,'

'

,

,

∑ ∑

∑

−−−−

−−−−

=Σ=

k j jk

j

k

j

n

jk

k

j jk

j

k

j

n

jk

k

n

k

n

Cx

Cx

xyp

σµ

σ

π

σµ

σ

π

πµ

2

2

2

2

2

1

2

1

1

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture2xing-150527174555-lva1-app6891/85/Lecture2-xing-9-320.jpg)

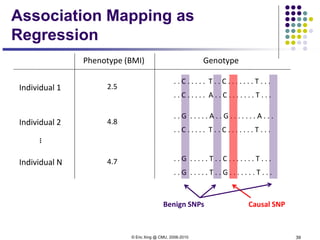

![© Eric Xing @ CMU, 2006-2010 31

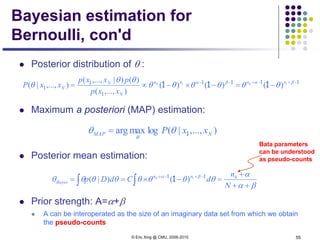

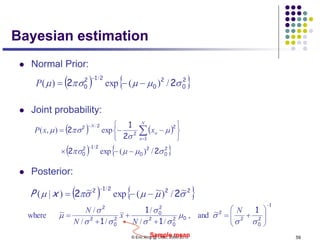

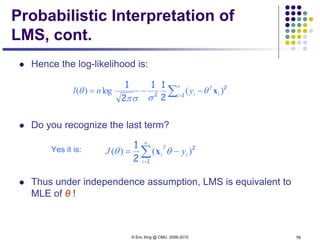

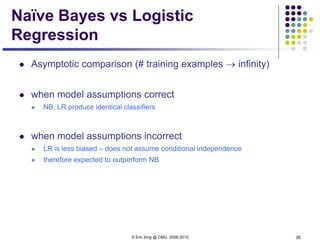

Naïve Bayes vs Logistic

Regression

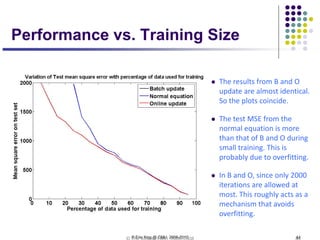

Non-asymptotic analysis (see [Ng & Jordan, 2002] )

convergence rate of parameter estimates – how many training

examples needed to assure good estimates?

NB order log m (where m = # of attributes in X)

LR order m

NB converges more quickly to its (perhaps less helpful)

asymptotic estimates](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture2xing-150527174555-lva1-app6891/85/Lecture2-xing-31-320.jpg)