This document provides an overview of the Situation Calculus, a formal logic framework for representing states, actions, and how actions transform states. It describes key components of the Situation Calculus including: (1) representing states as constants and using predicates to describe state properties, (2) representing actions and how they change state properties using effect axioms, (3) using frame axioms to represent properties that don't change with actions, and (4) generating plans by proving the existence of goal states and extracting the actions. Challenges with the approach include dealing with ramifications of actions and specifying all relevant preconditions and qualifications.

![7

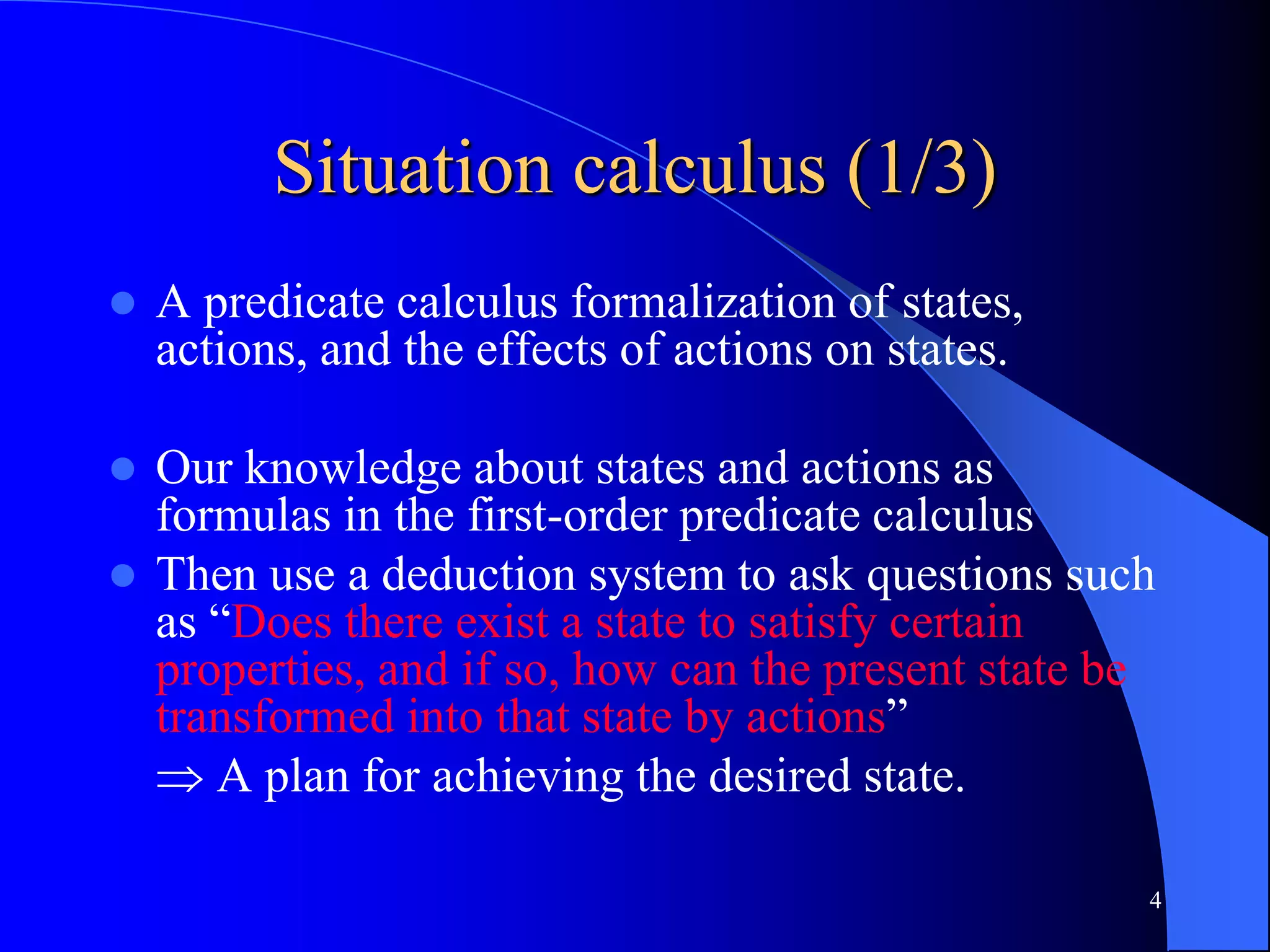

Example (Figure 21.1)

First-order predicate calculus

On(B,A)On(A,C)On(C,F1)Clear(B)…

True statement

On(B,A,S0)On(A,C,S0)On(C,F1,S0)Clear(B, S0)

Prepositions true of all states

(x,y,s)[On(x,y,s)(y=F1) Clear(y,s)]

(s)Clear(F1,s)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21situationcalculus-150601001712-lva1-app6892/75/21-situation-calculus-7-2048.jpg)

![9

Actions and the effects (2/2)

3. Express the effects of actions by wffs.

– There are two such wffs for each action-fluent

pair.

– For the pair {On, move}.

[On(x,y,s)Clear(x,s)Clear(z,s)(xz)

On(x,z,do(move(x,y,z),s))]

And [On(x,y,s)Clear(x,s)Clear(z,s)(xz)

On(x,z,do(move(x,y,z),s))]

positive effect axiom

negative effect axiom

preconditions

consequent](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21situationcalculus-150601001712-lva1-app6892/75/21-situation-calculus-9-2048.jpg)

![10

Effect axioms

We can also write effect axioms for the {Clear,

move} pair.

[On(x,y,s)Clear(x,s)Clear(z,s)(xz)(yz)

Clear(y,do(move(x,y,z),s))]

[On(x,y,s)Clear(x,s)Clear(z,s)(xz)(zF1)

Clear(z,do(move(x,y,z),s))]

The antecedents consist of two parts

– One part expresses the preconditions under which the

action can be executed

– The other part expresses the condition under which the

action will have the effect expressed in the consequent

of the axiom.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21situationcalculus-150601001712-lva1-app6892/75/21-situation-calculus-10-2048.jpg)

![13

21.2.1 Frame Axioms (2/3)

The frame axioms for the pair, {(move, On)}

[On(x,y,s)(xu)] On(x,y,do(move(u,y,z),s))

(On(x,y,s)[(xu)(yz)] On(x,y,do(move(u,v,z),s))

The frame axioms for the pair, {move,

Clear}

Clear(u,s)(uz)] Clear(u,do(move(x,y,z),s))

Clear(u,s)(uy) Clear(u,do(move(x,y,z),s))

positive frame axioms negative frame axioms](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21situationcalculus-150601001712-lva1-app6892/75/21-situation-calculus-13-2048.jpg)

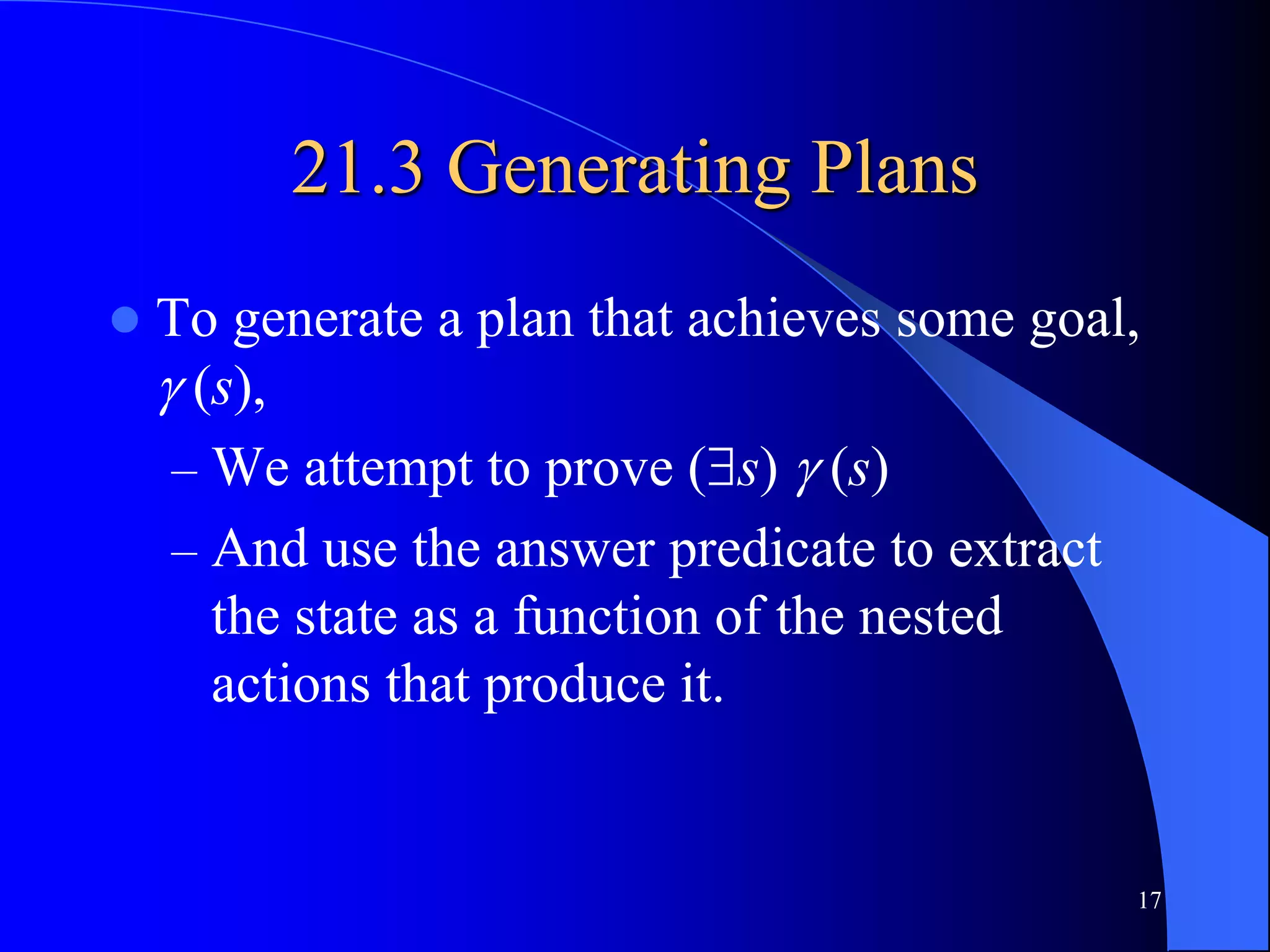

![19

Example (Figure 21.1) (2/2)

On(A,C,S0)

On(C,F1,S0)

Clear(B,S0)

Clear(F1,S0)

[On(x,y,s)Clear(x,s) Clear(z,s) (xz)

On(x,z,do(move(x,y,z),s))]

(s) On(B,F1,s) ?

Answer: ans(do(move(B,A,F1),S0))](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21situationcalculus-150601001712-lva1-app6892/75/21-situation-calculus-19-2048.jpg)