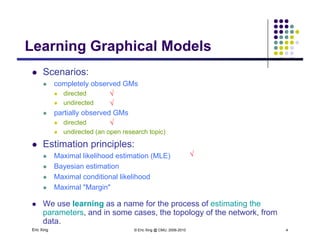

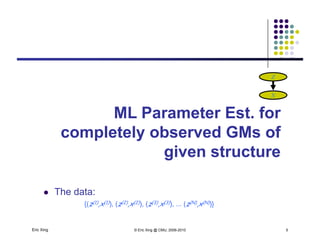

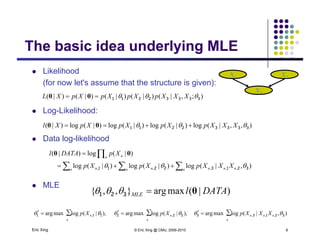

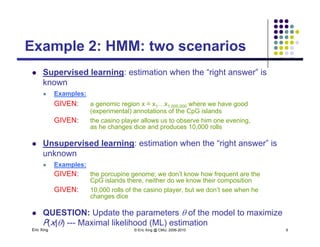

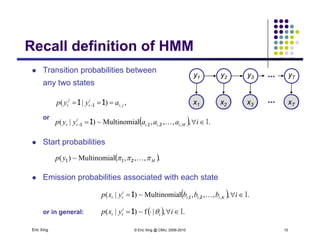

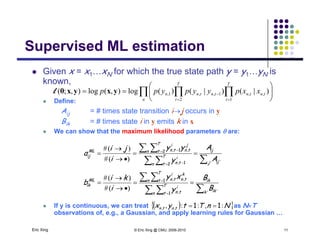

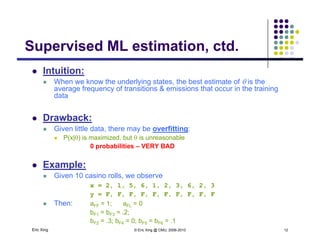

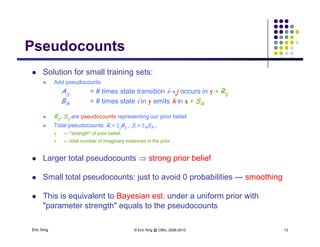

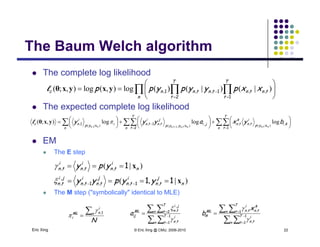

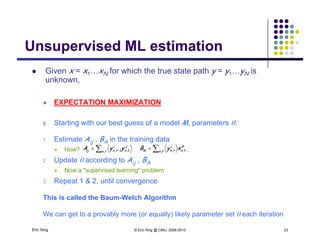

The document discusses learning graphical models from data. It describes two main tasks: inference, which is computing answers to queries about a probability distribution described by a Bayesian network, and learning, which is estimating a model from data. It provides examples of learning for completely observed models, including maximum likelihood estimation for the parameters of a conditional Gaussian model. It also discusses supervised versus unsupervised learning of hidden Markov models, and techniques for dealing with small training sets like adding pseudocounts to estimates.

![Example 1: conditional Gaussian

The completely observed model: Z

Example 1: conditional Gaussian

p y

Z is a class indicator vector

Z

X

110

2

1

∑and][where mm

ZZ

Z

Z

Z 110

∑and],,[where,

m

M

ZZ

Z

Z

zzzi M

zp )|(

21

1

All except one

of these terms

and a datum is in class i w.p. i

X i diti l G i i bl ith l ifi

m

z

m

Mi

m

zp

zp

)(

)|( 211 will be one

X is a conditional Gaussian variable with a class-specific mean

2

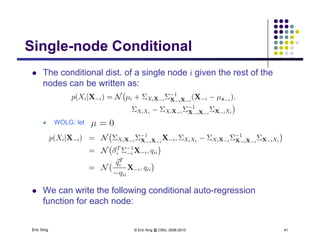

2

1

212 2

2

1

1 )-(-exp

)(

),,|( / m

m

xzxp

Eric Xing © Eric Xing @ CMU, 2006-2010 7

)(

m

z

m

m

xNzxp ),|(),,|( ∏ ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture12xing-150527174444-lva1-app6891/85/Lecture12-xing-7-320.jpg)

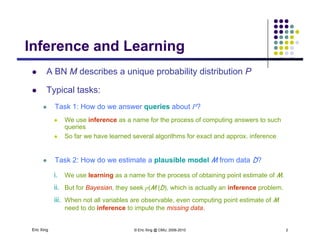

![Learning (sparse) GGMLearning (sparse) GGM

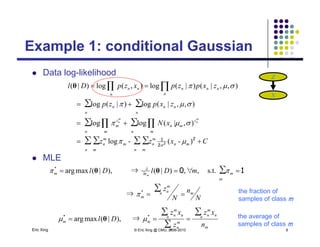

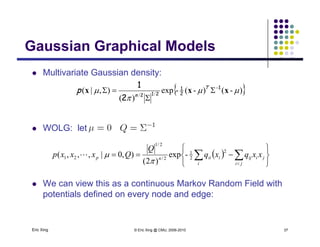

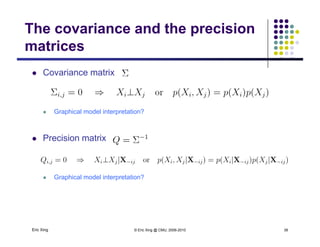

Multivariate Gaussian over all continuous expressions

{ })-()-(-exp

||)2(

1

=]),...,([ 1-

2

1

1 2

1

2

xxxxp T

n n

p

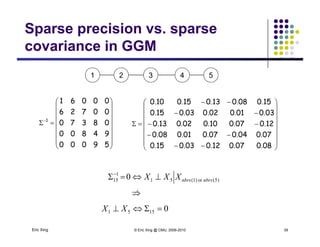

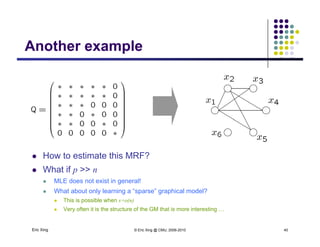

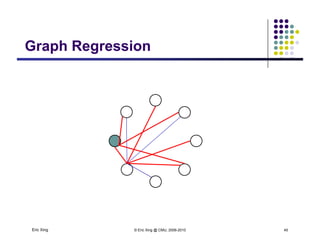

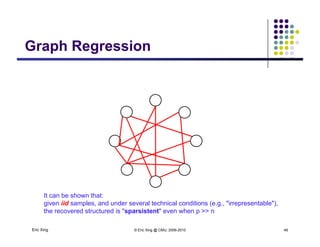

The precision matrix Q reveals the topology of the

(undirected) network

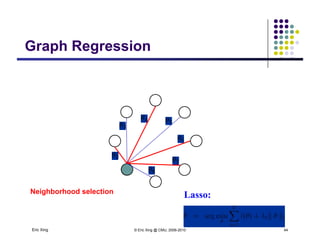

Learning Algorithm: Covariance selection

Want a sparse matrix Q

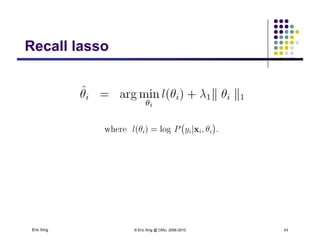

As shown in the previous slides, we can use L_1 regularized linear

regression to obtain a sparse estimate of the neighborhood of each

variable

Eric Xing © Eric Xing @ CMU, 2006-2010 48](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture12xing-150527174444-lva1-app6891/85/Lecture12-xing-48-320.jpg)

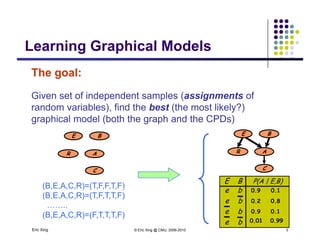

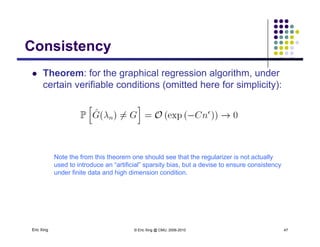

![Recent trends in GGM:Recent trends in GGM:

Covariance selection (classical L1-regularization based

method)

Dempster [1972]:

Sequentially pruning smallest elements

in precision matrix

method (hot !)

Meinshausen and Bühlmann [Ann. Stat.

06]:

Used LASSO regression forin precision matrix

Drton and Perlman [2008]:

Improved statistical tests for pruning

Used LASSO regression for

neighborhood selection

Banerjee [JMLR 08]:

Block sub-gradient algorithm for finding

precision matrixp

Friedman et al. [Biostatistics 08]:

Efficient fixed-point equations based

on a sub-gradient algorithm

…

Serious limitations in

ti b k d h

…

practice: breaks down when

covariance matrix is not

invertible

Structure learning is possible

Eric Xing © Eric Xing @ CMU, 2006-2010 49

Structure learning is possible

even when # variables > #

samples](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture12xing-150527174444-lva1-app6891/85/Lecture12-xing-49-320.jpg)