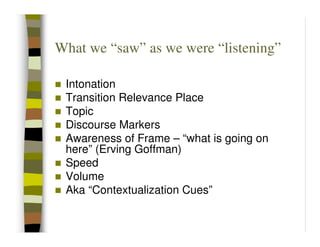

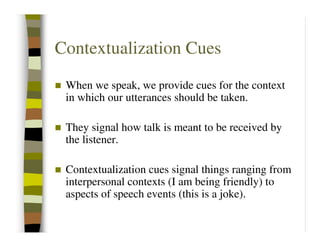

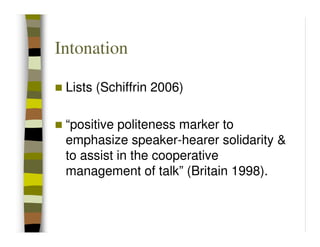

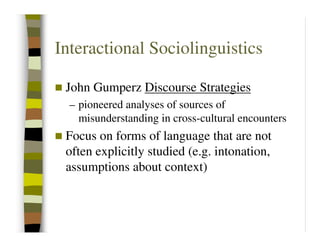

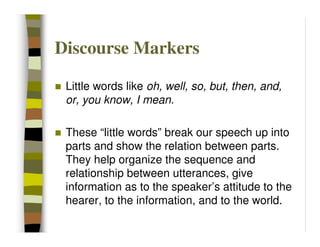

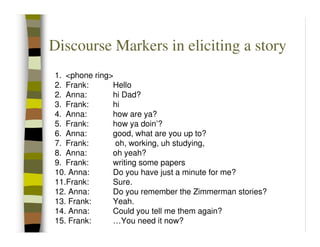

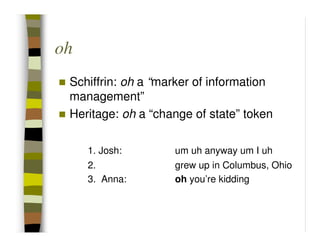

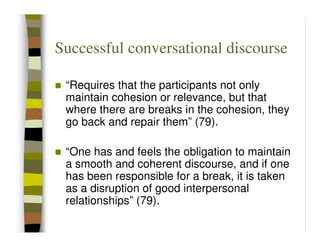

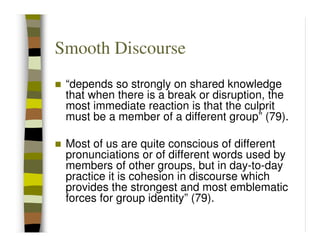

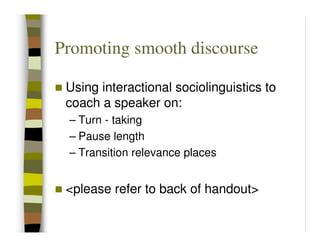

Dr. Anna Marie Trester and Sonia Checchia from Georgetown University's Linguistics Department discuss sociolinguistics and its application to cross-cultural training. They explain key concepts from interactional sociolinguistics like contextualization cues, speech acts, discourse markers and referencing expressions that can enhance understanding of language and social interaction. The presentation demonstrates these concepts and how they reveal cultural assumptions. It aims to add analytical tools to help recognize how power and perspective are communicated through language.