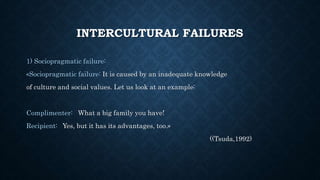

Intercultural communication takes place when individuals from different cultural communities interact and negotiate shared meanings. Defining appropriate language use and nonverbal communication patterns can vary across cultures. Developing intercultural competence requires avoiding ethnocentrism and being sensitive to differences in areas like time orientation, values, and worldviews between cultures. Theories of intercultural communication aim to understand these cultural differences and how they can lead to misunderstandings if not properly navigated, such as through failures in sociopragmatic or pragmalinguistic use of language.

![WHAT IS PRAGMATIC FAILURE?

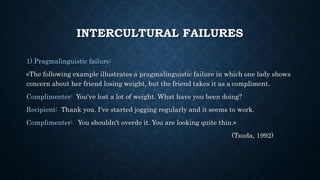

• Thomas (1983), in her discussion of “pragmatic failure”, has identified two types of

failure, one of them being “pragmalinguistic failure”, which “occurs when the pragmatic

force mapped by [the speaker] onto a given utterance is systematically different from the

force most frequently assigned to it by native speakers of the target language, or when

speech act strategies are inappropriately transferred from L1 to L2” (p. 99). Such

“inappropriate” transfer has also been labeled “negative transfer” - “the influence of L1

pragmatic competence on [interlanguage] pragmatic knowledge that differs from the L2

target” (Kasper & Blum-Kulka, 1993, p. 10). Transfer can also be “positive”, which refers

to the instances of “pragmatic behaviors … consistent across L1, [interlanguage], and

L2” (ibid.). However, whether positive or negative, both definitions of transfer make it

obvious that the appropriateness of language use is judged by the “native speakers” of

the L2.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/interculturalsonn-151025130254-lva1-app6891/85/Intercultural-Pragmatics-34-320.jpg)

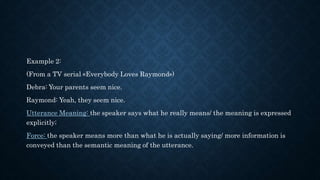

![AMERICAN VS. CHINESE

Here is an interview of Mei;

«Mei is a 19-year-old female from China, a native speaker of Mandarin. She had been studying English in China for about

8 years and had been in the United States as a university student for about 2 years at the time of the study.

Mei: I think it’s - I think it’s different American than China- Chinese culture

R: what is the difference?

Mei: I think American people say all- most - most of all the things directly

[uhum] but Chinese people we’re kind of like - not very directly find some like

uhh softer way to say that [uhum] but not too directly

R: uhum and why is that?

Mei: I don’t know I think the culture I grew up it’s like this so - our thoughts and

our opinion is - that -- yeah [uhum] cause when I come here I think American

people say all things so directly but not a- Chinese people won’t say that»

(Kuchuk, 2012)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/interculturalsonn-151025130254-lva1-app6891/85/Intercultural-Pragmatics-37-320.jpg)