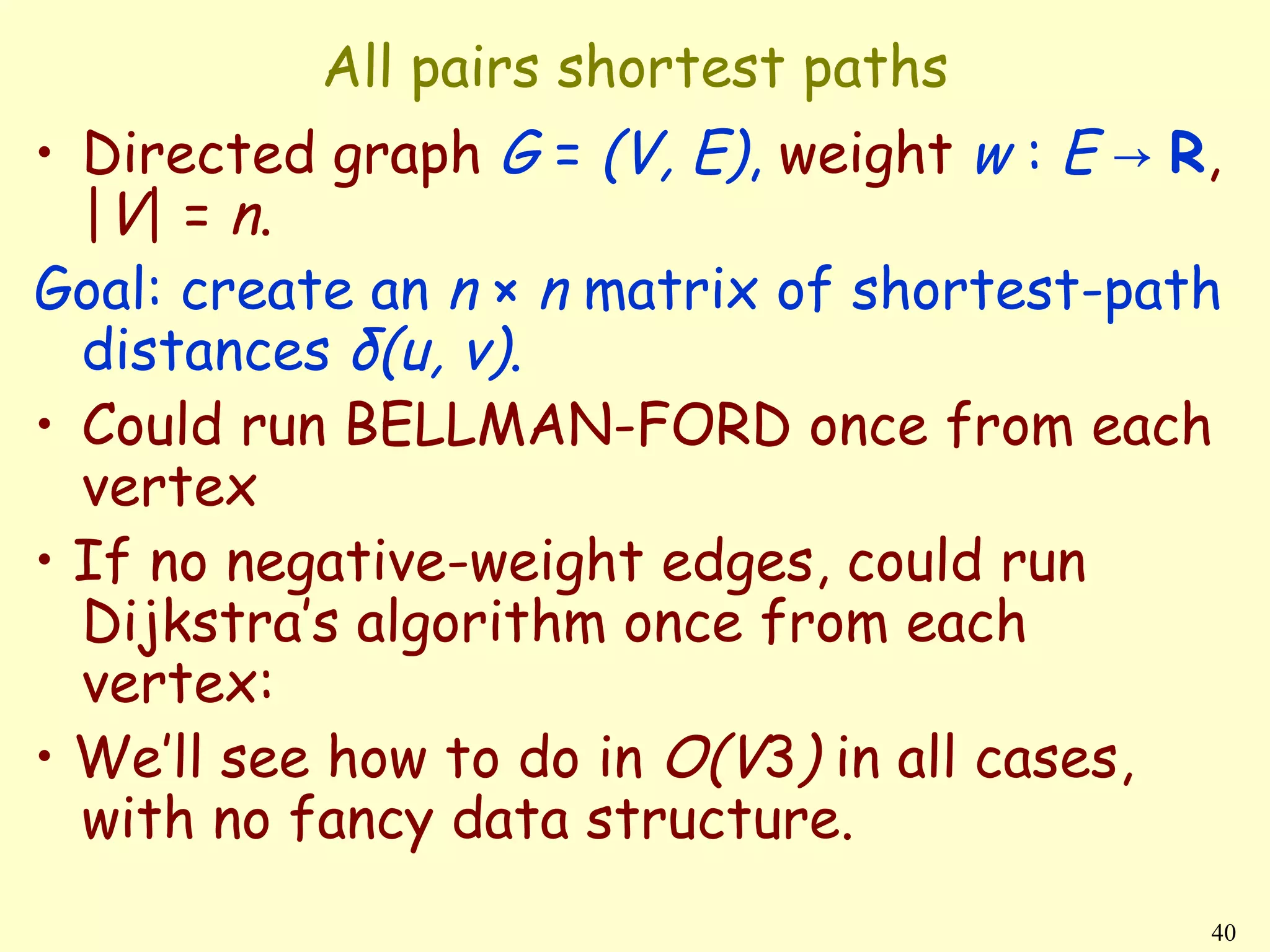

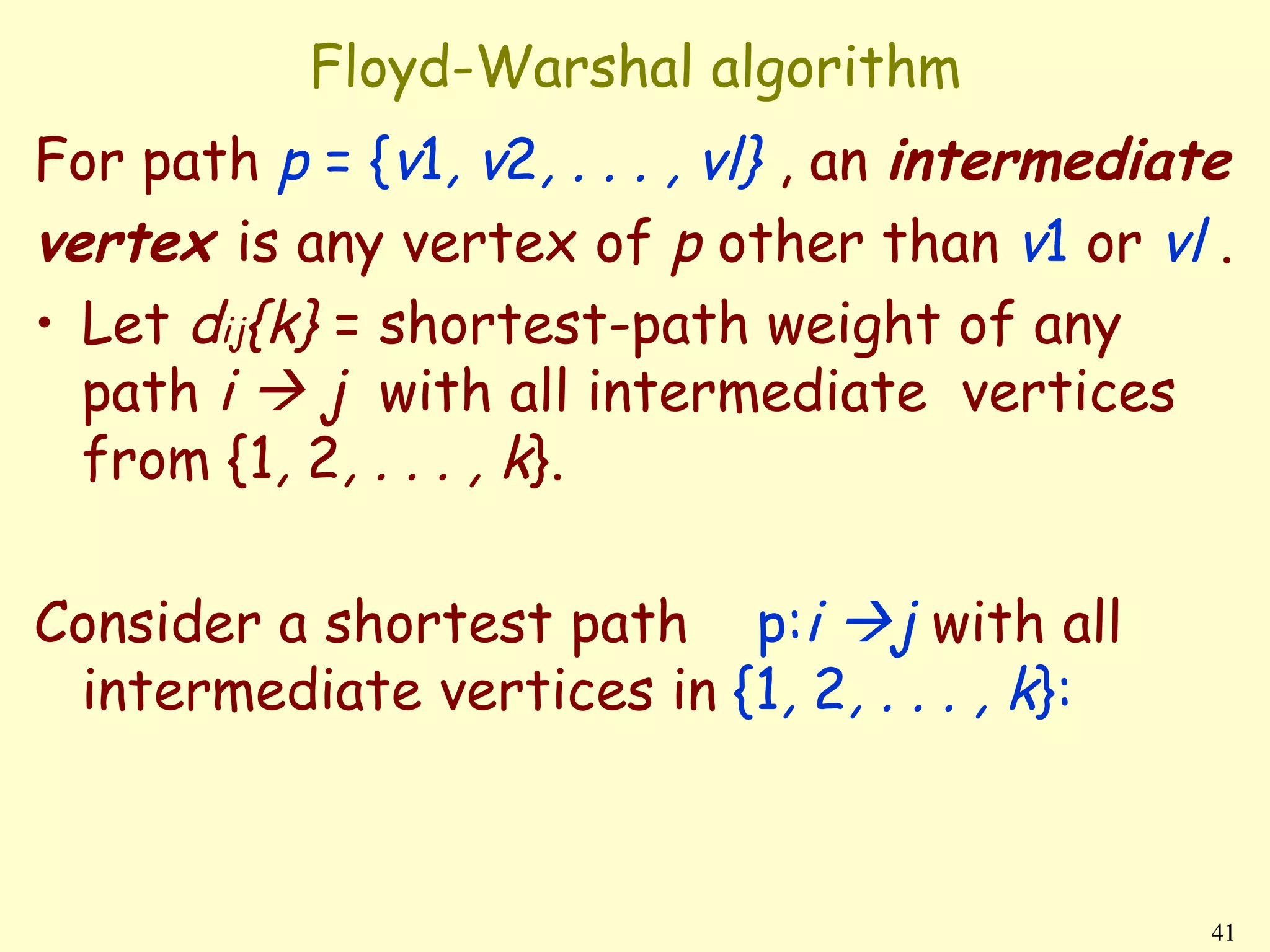

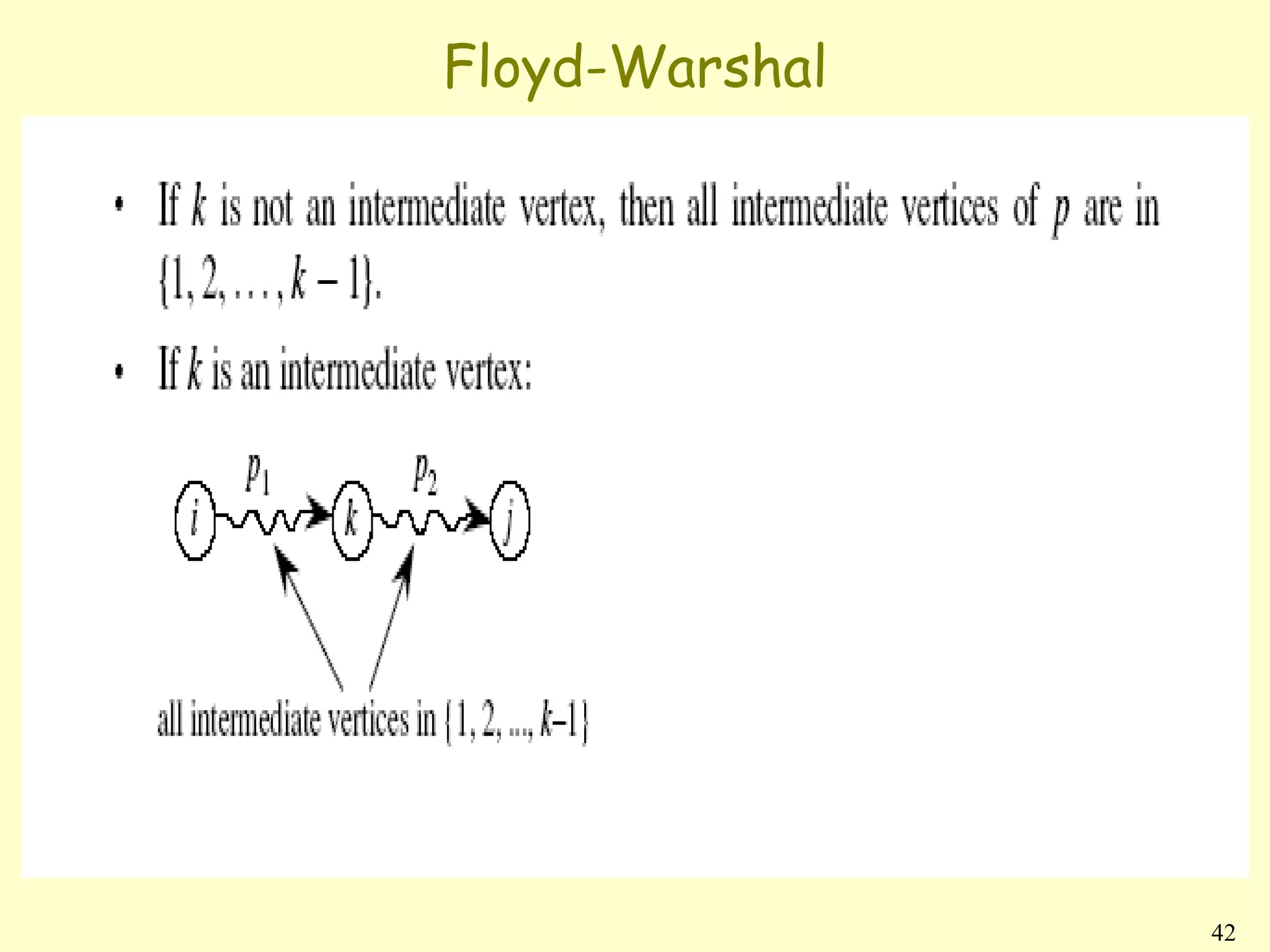

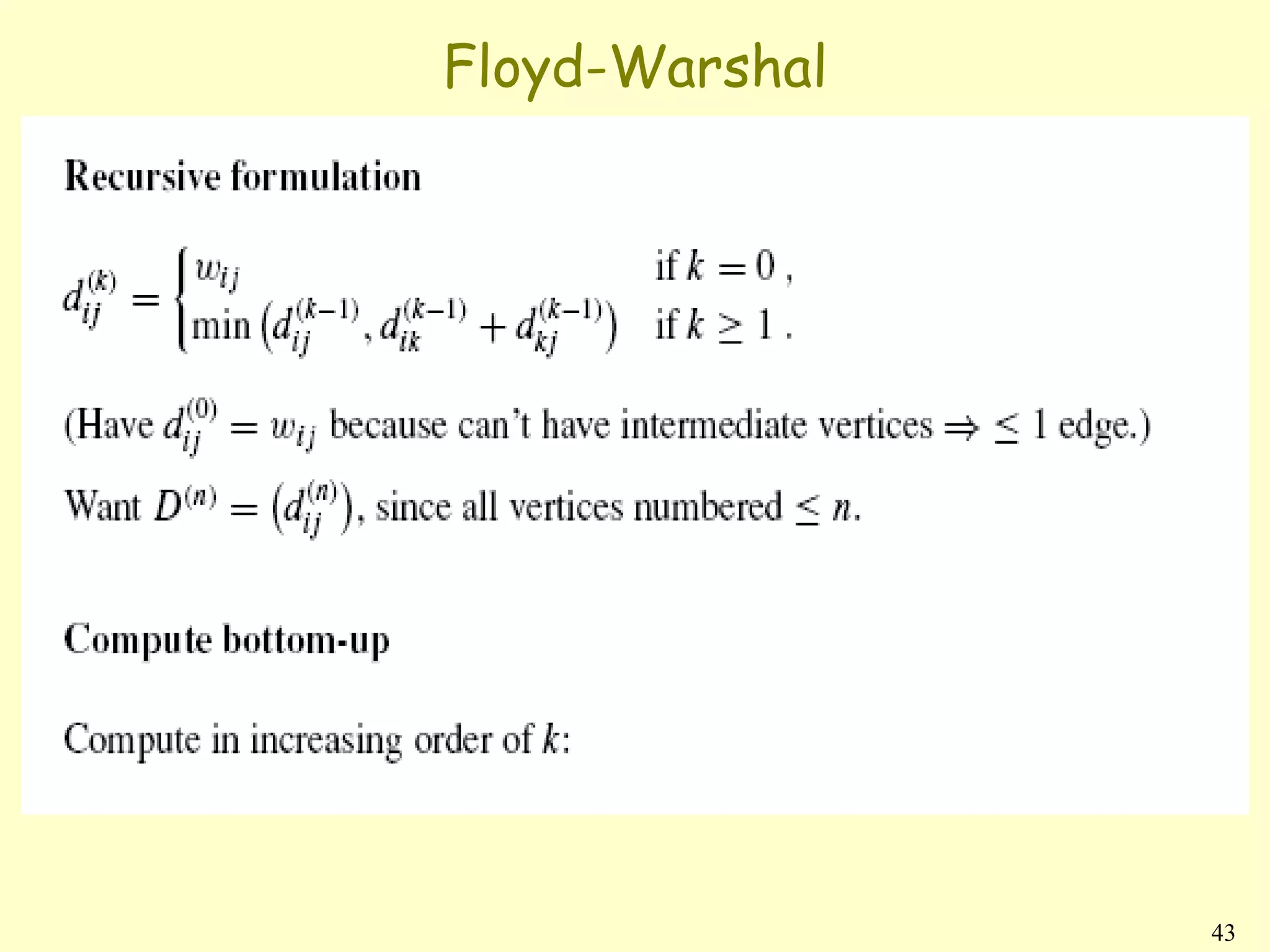

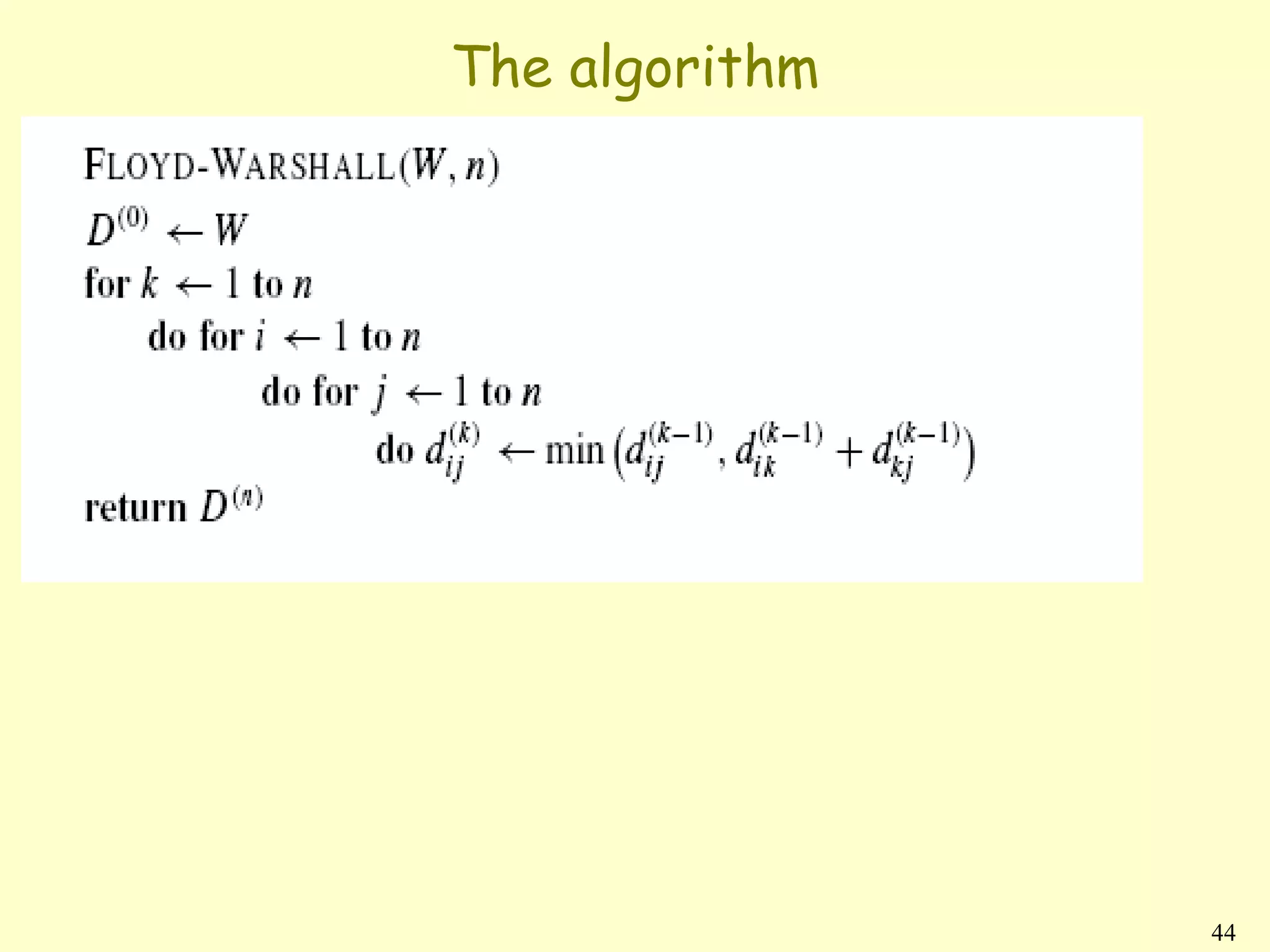

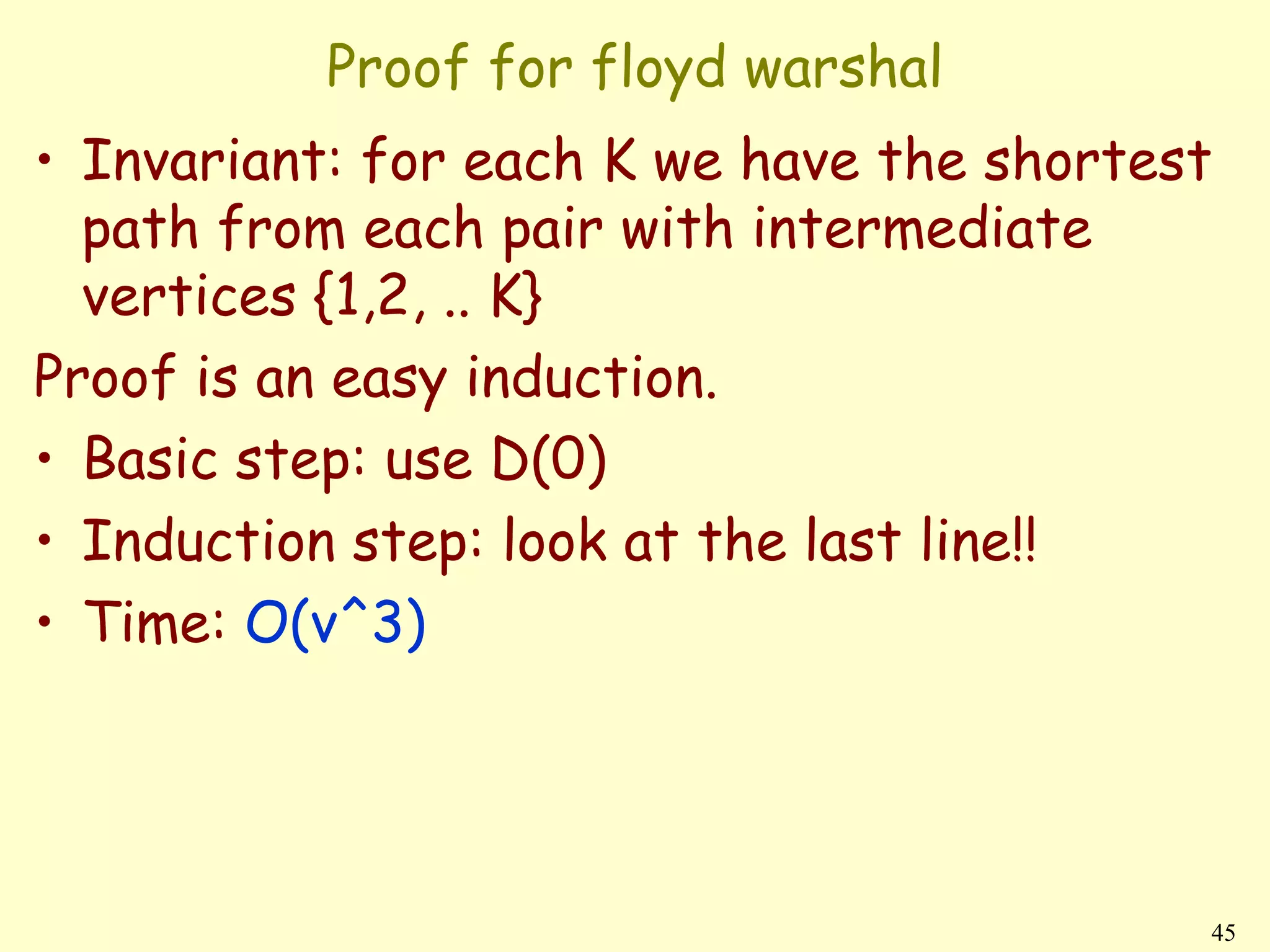

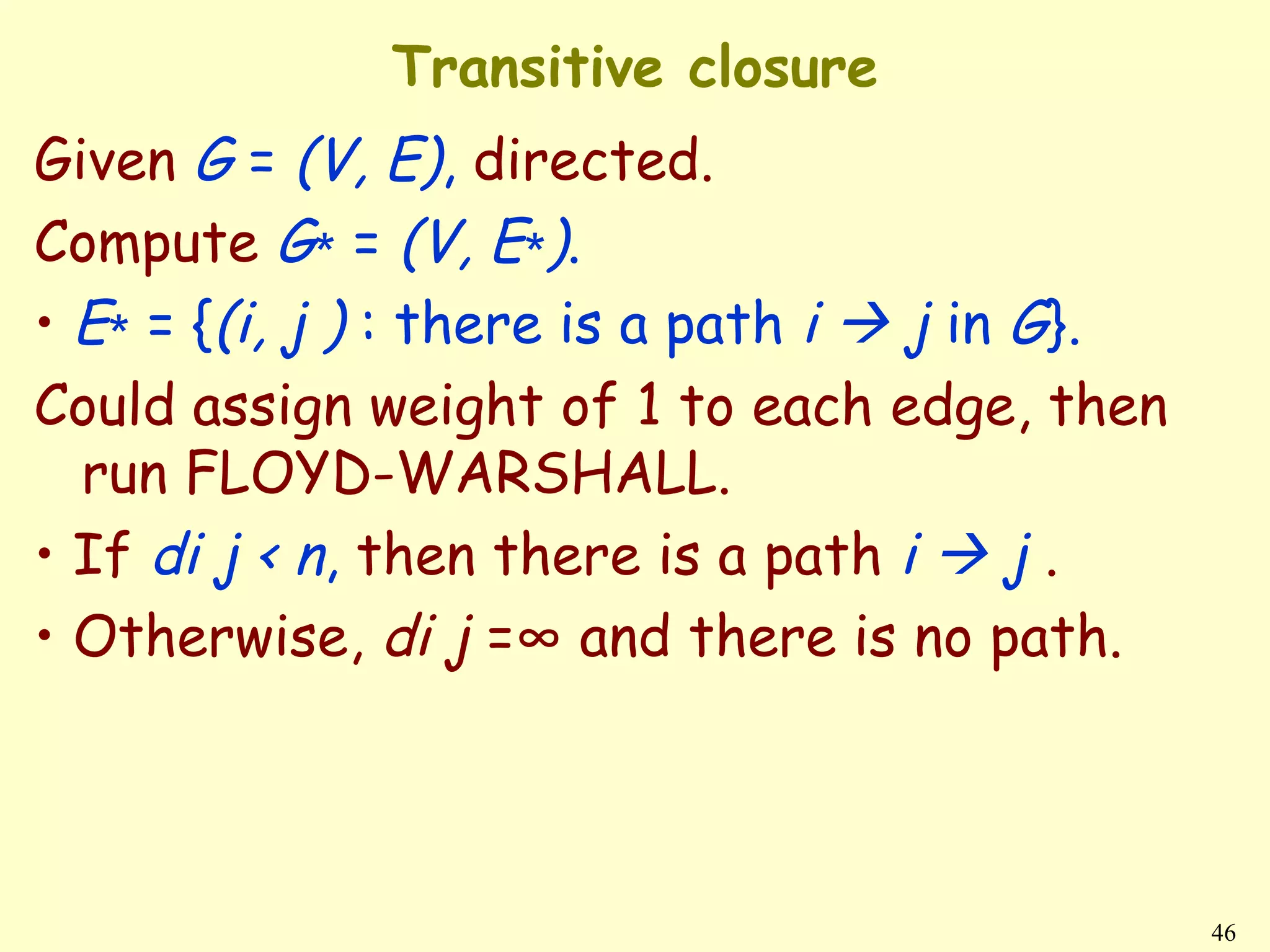

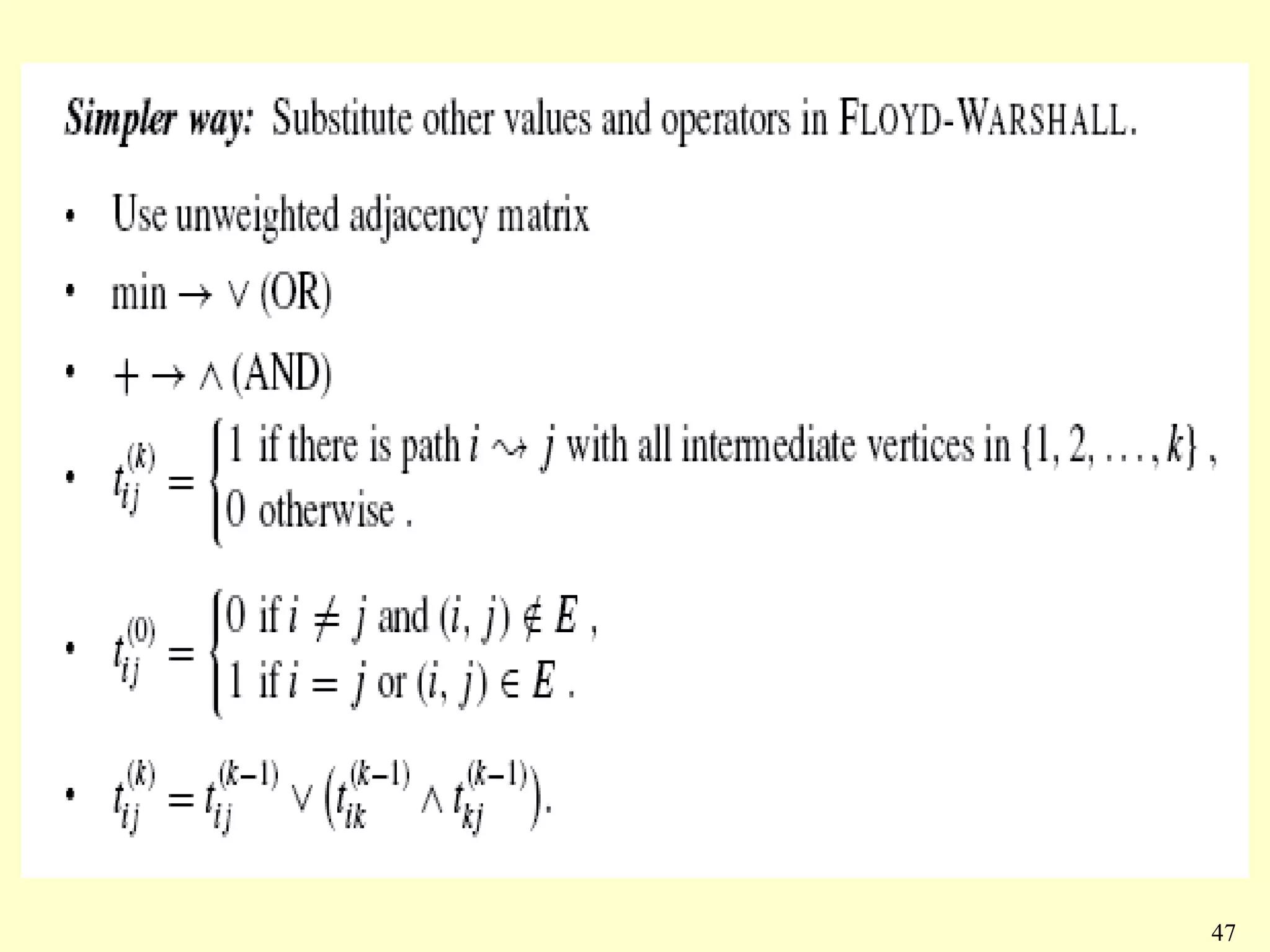

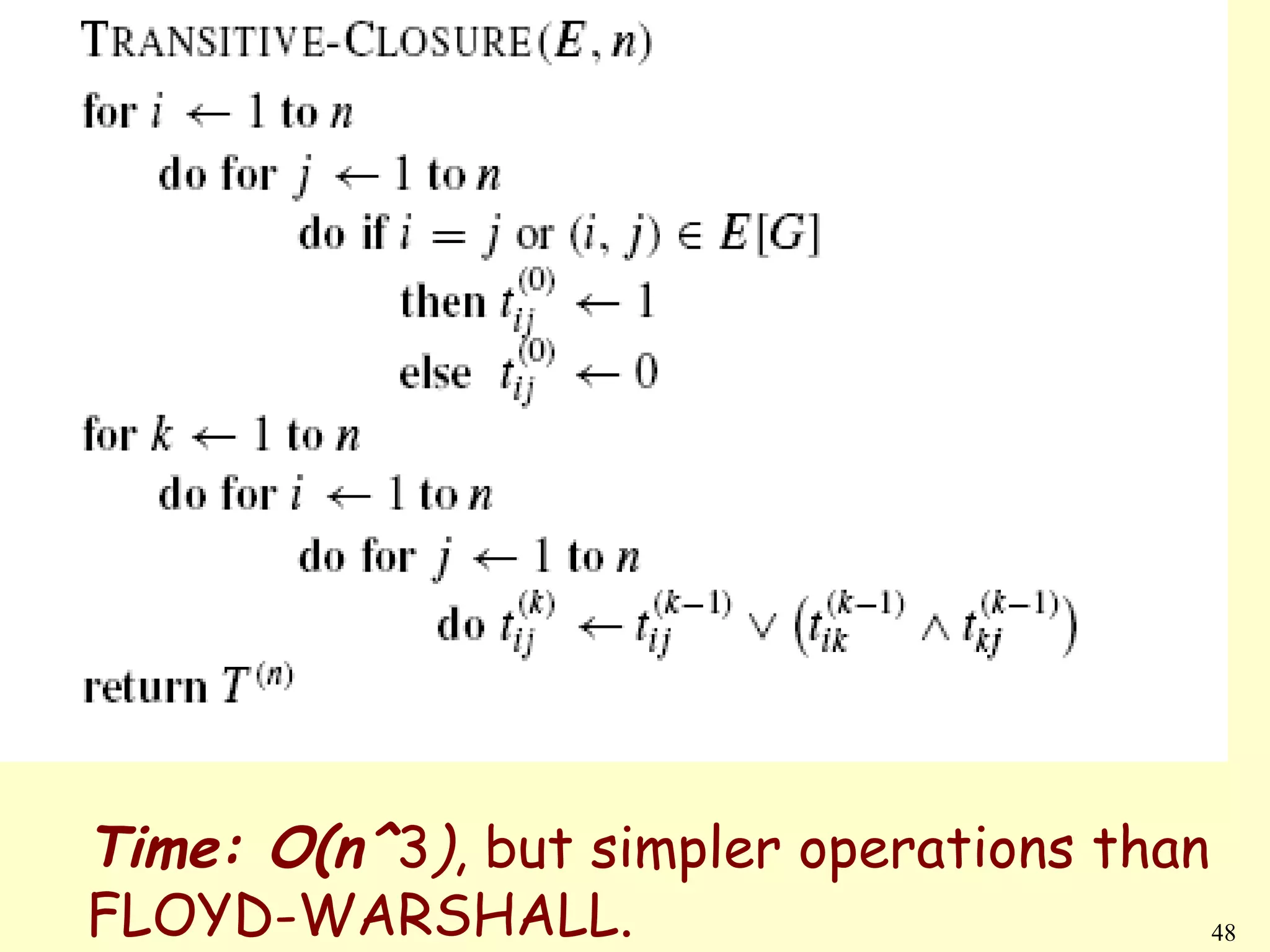

The document discusses shortest path algorithms for graphs. It defines different variants of shortest path problems like single-source, single-destination, and all-pairs shortest paths. It presents algorithms like Bellman-Ford, Dijkstra's algorithm, and Floyd-Warshal algorithm to solve these problems. Bellman-Ford handles negative edge weights but has a higher time complexity of O(V^3) compared to Dijkstra's which only works for positive edges. Floyd-Warshal solves the all-pairs shortest paths problem in O(V^3) time using dynamic programming and matrix multiplication.

![Lemma 1)

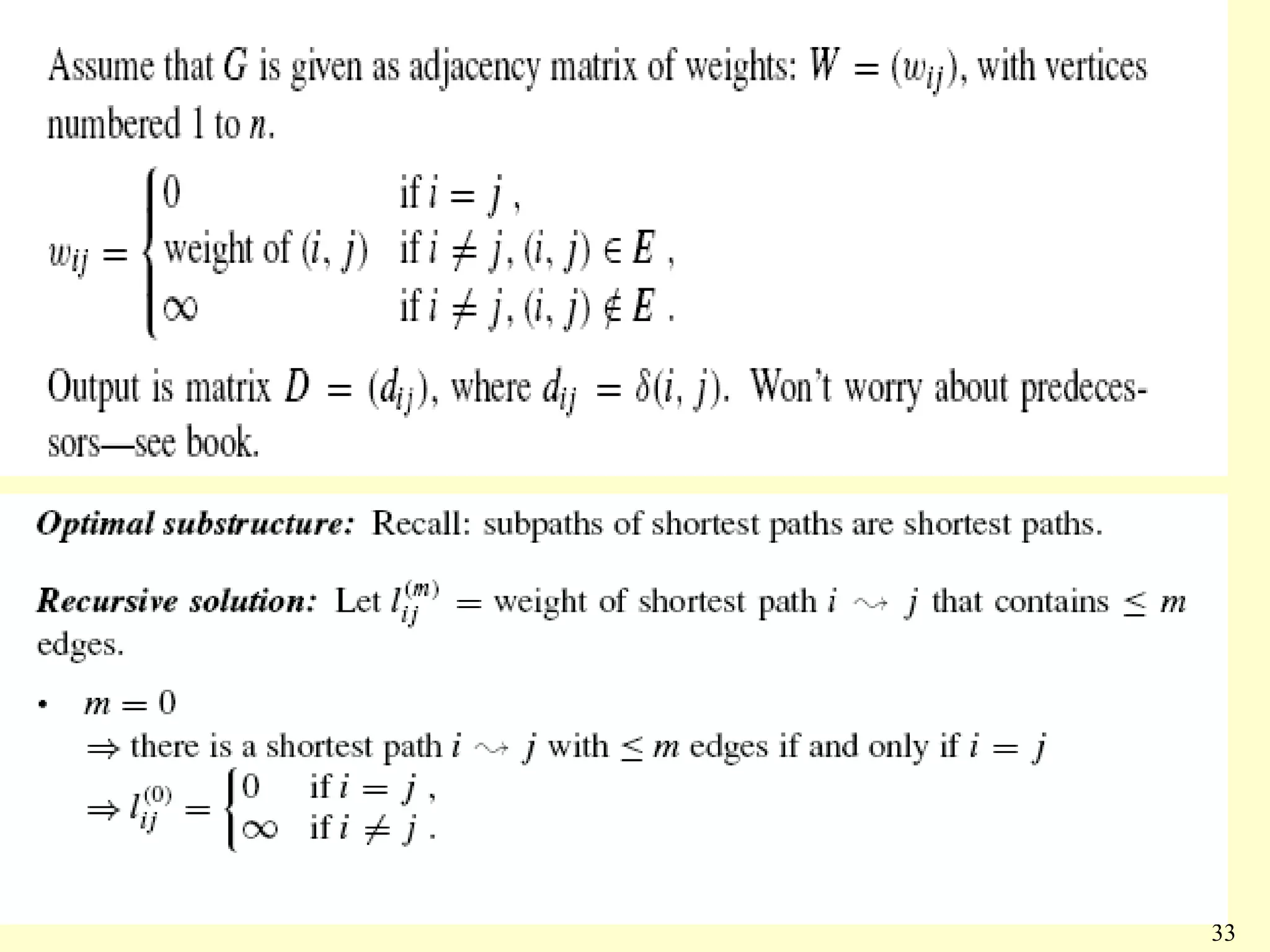

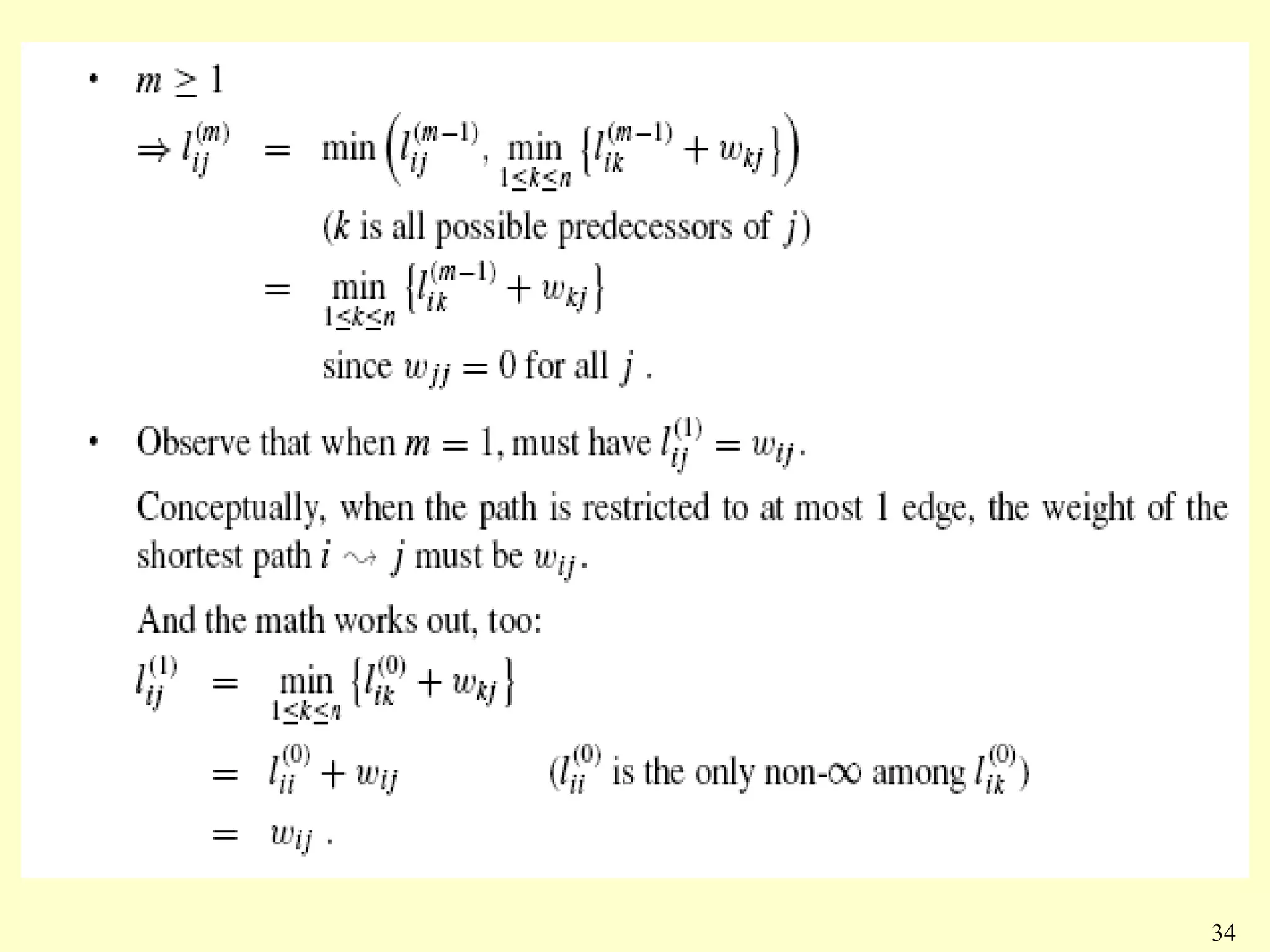

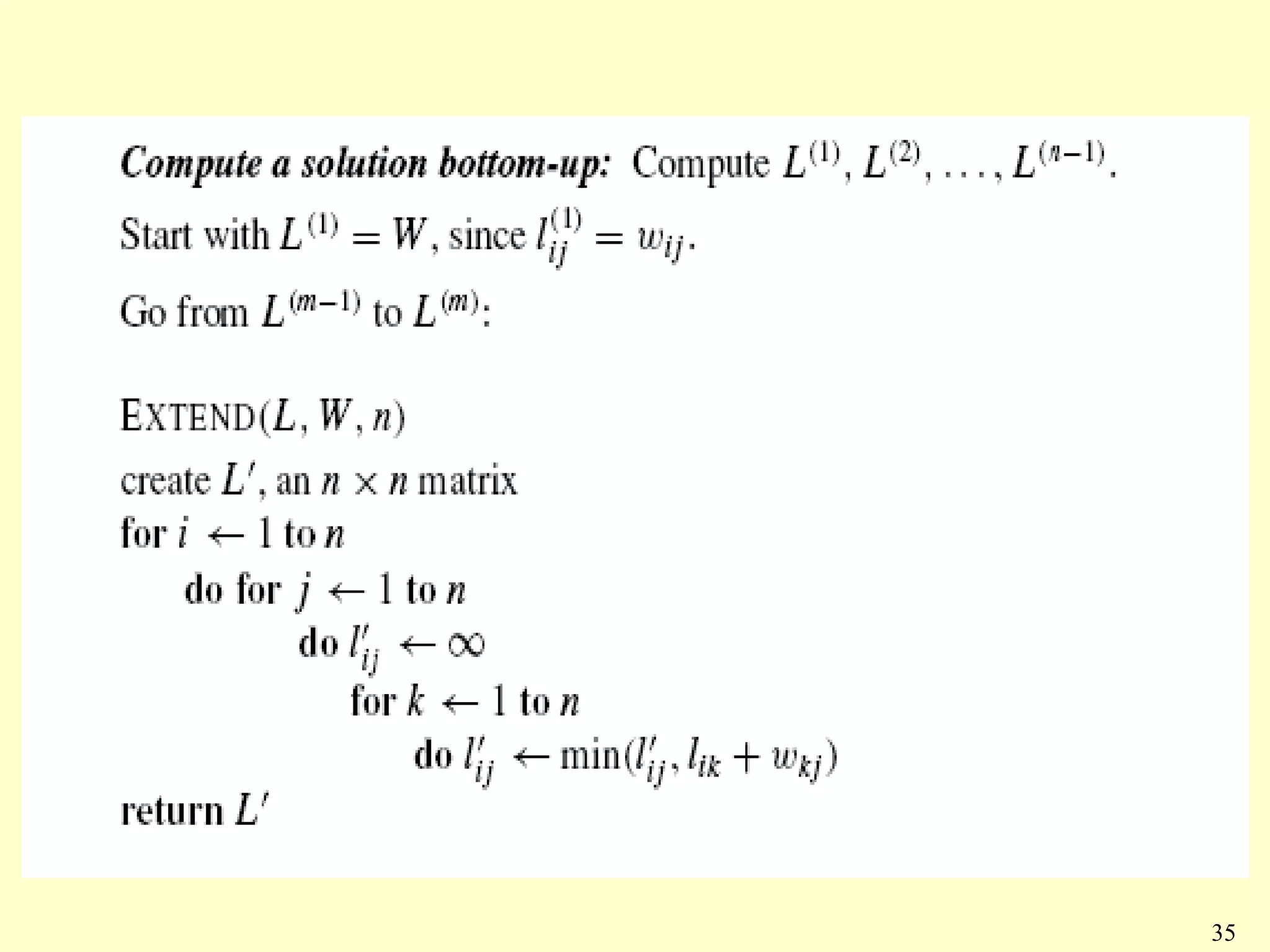

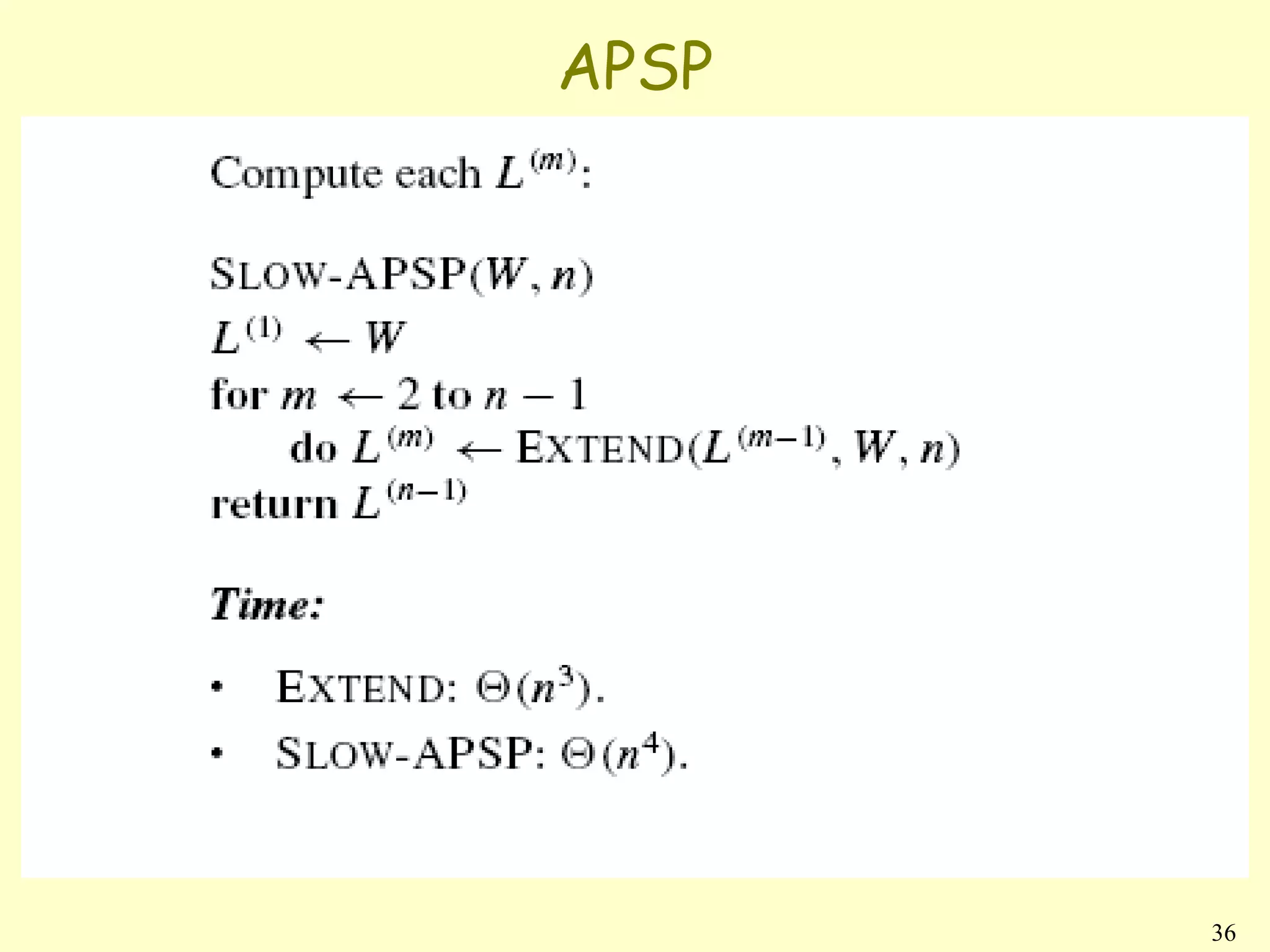

• Optimal substructure lemma: Any sub-path of

a shortest path is a shortest path.

• Shortest paths can’t contain cycles:

proofs: rather trivial.

• We use the d[v] array at all times

INIT-SINGLE-SOURCE(V, s)

{

for each v in V{

d[v]←∞

π[v] ← NIL

}

d[s] ← 0

}

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lect14-120617042852-phpapp02/75/Inroduction_To_Algorithms_Lect14-6-2048.jpg)

![Relaxing

RELAX(u, v, w){

if d[v] > d[u] + w(u, v) then{

d[v] ← d[u] + w(u, v)

π[v]← u

}

}

For all the single-source shortest-paths

algorithms we’ll do the following:

• start by calling INIT-SINGLE-SOURCE,

• then relax edges.

The algorithms differ in the order and

how many times they relax each edge.

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lect14-120617042852-phpapp02/75/Inroduction_To_Algorithms_Lect14-7-2048.jpg)

![Lemma 3) Upper-bound property

1) Always have d[v] ≥ δ(s, v) for all v.

2) Once d[v] = δ(s, v), it never changes.

Proof Initially true.

• Suppose there exists a vertex such that

d[v] < δ(s, v). Without loss of generality, v is first

vertex for which this happens.

• Let u be the vertex that causes d[v] to change.

Then d[v] = d[u] + w(u, v).

So, d[v] < δ(s, v)

≤ δ(s, u) + w(u, v) (triangle inequality)

≤ d[u] + w(u, v) (v is first violation)

d[v] < d[u] + w(u, v) .

Contradicts d[v] = d[u] + w(u, v).

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lect14-120617042852-phpapp02/75/Inroduction_To_Algorithms_Lect14-9-2048.jpg)

![Lemma 4: Convergence property

If s ---> u → v is a shortest path and

d[u] = δ(s, u), and we call RELAX(u,v,w), then

d[v] = δ(s, v) afterward.

Proof: After relaxation:

d[v] ≤ d[u] + w(u, v) (RELAX code)

= δ(s, u) + w(u, v) (assumption)

= δ(s, v) (Optimal substructure lemma)

Since d[v] ≥ δ(s, v), must have d[v] = δ(s, v).

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lect14-120617042852-phpapp02/75/Inroduction_To_Algorithms_Lect14-10-2048.jpg)

![(Lemma 5) Path relaxation property

Let p = v0, v1, . . . , vk be a shortest path from s = v0

to vk .

If we relax, in order, (v0, v1), (v1, v2), . . . , (Vk−1,

Vk), even intermixed with other relaxations,

then d[Vk ] = δ(s, Vk ).

Proof Induction to show that d[vi ] = δ(s, vi ) after

(vi−1, vi ) is relaxed.

Basis: i = 0. Initially, d[v0] = 0 = δ(s, v0) = δ(s, s).

Inductive step: Assume d[vi−1] = δ(s, vi−1). Relax

(vi−1, vi ). By convergence property, d[vi ] = δ(s,

vi ) afterward and d[vi ] never changes.

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lect14-120617042852-phpapp02/75/Inroduction_To_Algorithms_Lect14-11-2048.jpg)

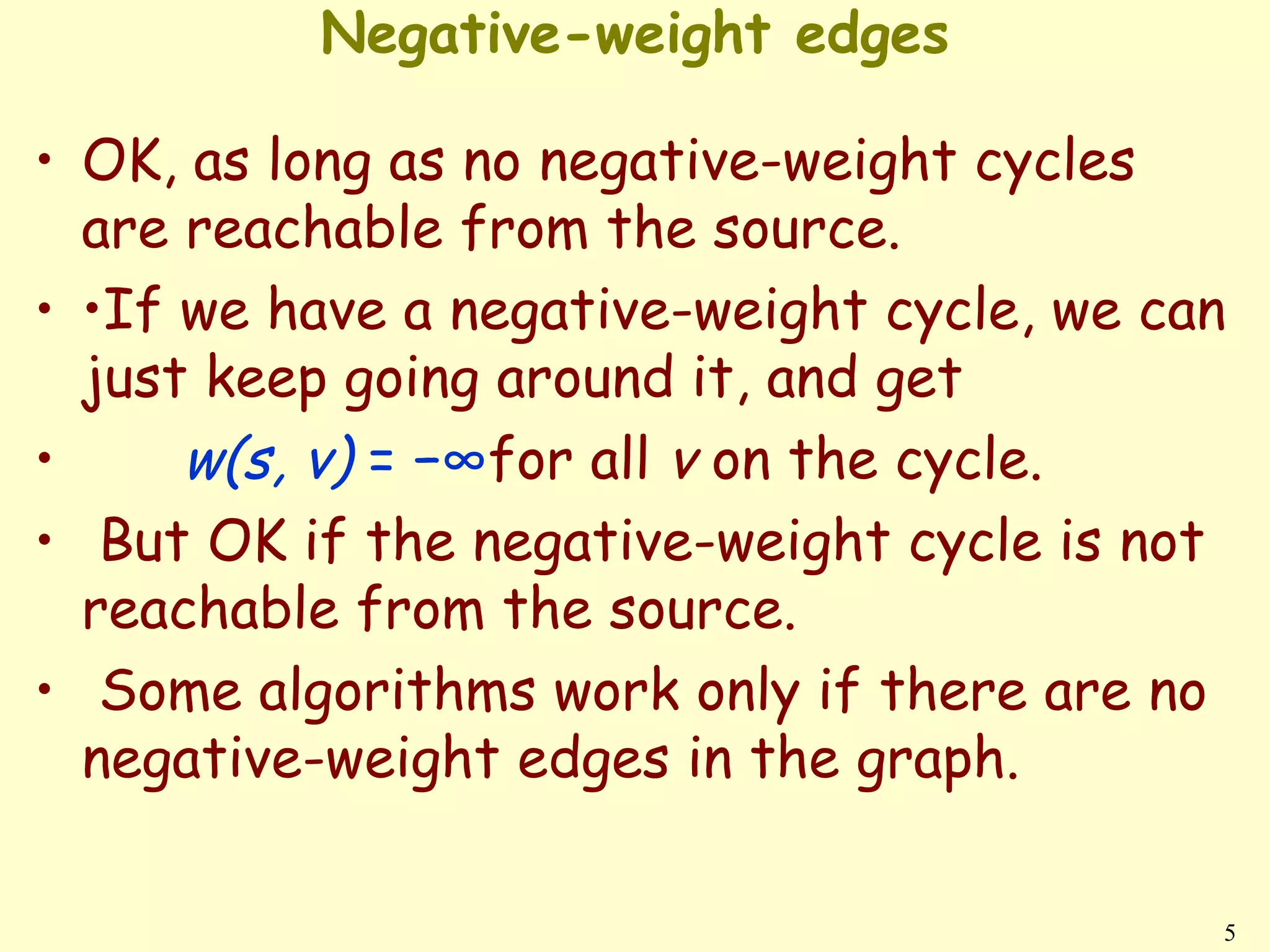

![The Bellman-Ford algorithm

• Allows negative-weight edges.

• Computes d[v] and π[v] for all v inV.

• Returns TRUE if no negative-weight cycles

reachable from s, FALSE otherwise.

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lect14-120617042852-phpapp02/75/Inroduction_To_Algorithms_Lect14-12-2048.jpg)

![Bellman-ford

BELLMAN-FORD(V, E, w, s){

INIT-SINGLE-SOURCE(V, s)

for i ← 1 to |V| − 1

for each edge (u, v) in E

RELAX(u, v, w)

for each edge (u, v) in E

if d[v] > d[u] + w(u, v)

return FALSE

return TRUE

}

Time: O(V*E)= O(V^3) in the worst case.

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lect14-120617042852-phpapp02/75/Inroduction_To_Algorithms_Lect14-13-2048.jpg)

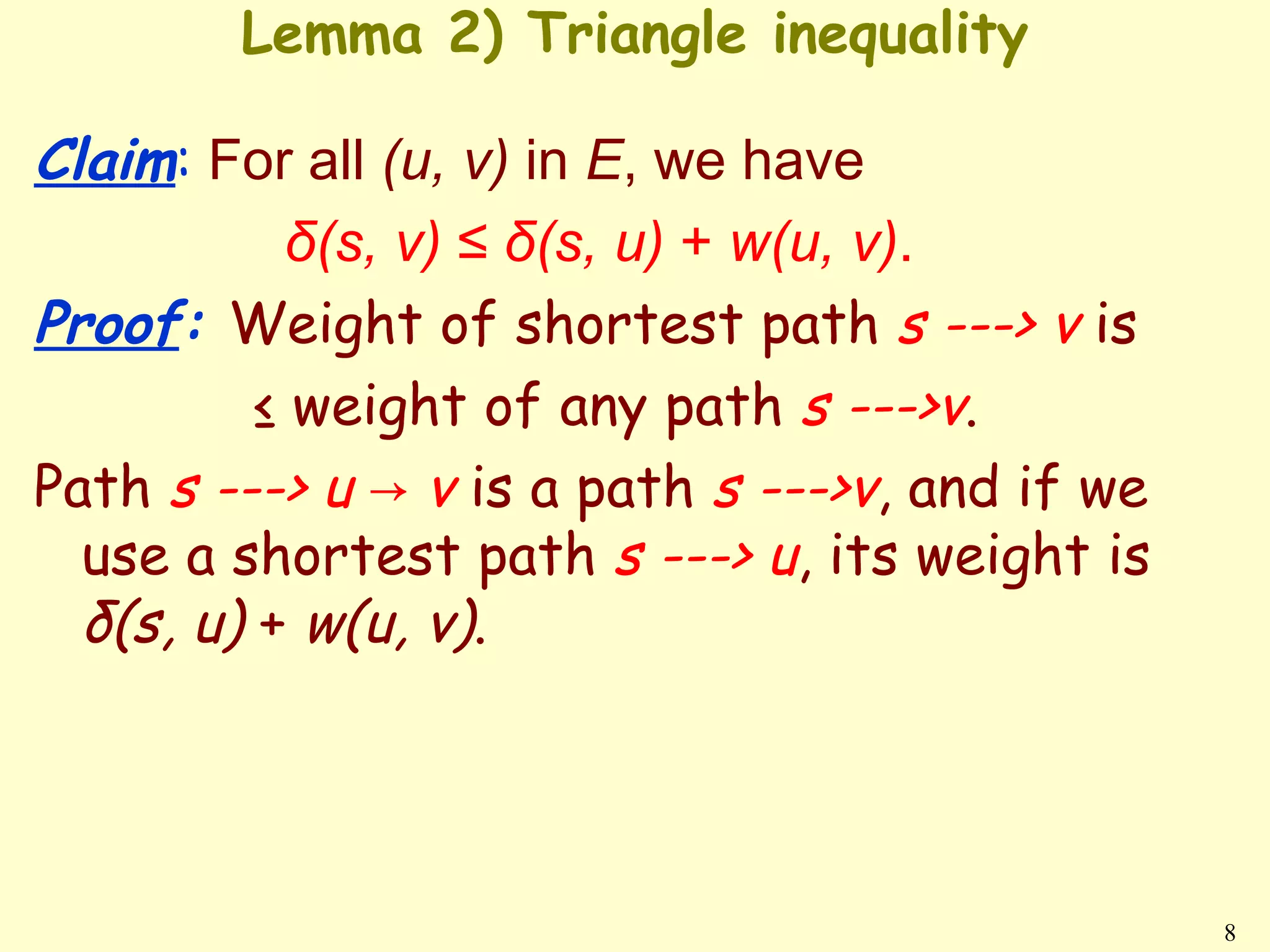

![Correctness of Belman-Ford

Let v be reachable from s, and let p = {v0, v1, . . . , vk}

be a shortest path from s v,

where v0 = s and vk = v.

• Since p is acyclic, it has ≤ |V| − 1 edges, so k ≤|V|−1.

Each iteration of the for loop relaxes all edges:

• First iteration relaxes (v0, v1).

• Second iteration relaxes (v1, v2).

• kth iteration relaxes (vk−1, vk).

By the path-relaxation property,

d[v] = d[vk ] = δ(s, vk ) = δ(s, v).

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lect14-120617042852-phpapp02/75/Inroduction_To_Algorithms_Lect14-14-2048.jpg)

![How about the TRUE/FALSE return value?

• Suppose there is no negative-weight cycle

reachable from s.

At termination, for all (u, v) in E,

d[v] = δ(s, v)

≤ δ(s, u) + w(u, v) (triangle inequality)

= d[u] + w(u, v) .

So BELLMAN-FORD returns TRUE.

15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lect14-120617042852-phpapp02/75/Inroduction_To_Algorithms_Lect14-15-2048.jpg)

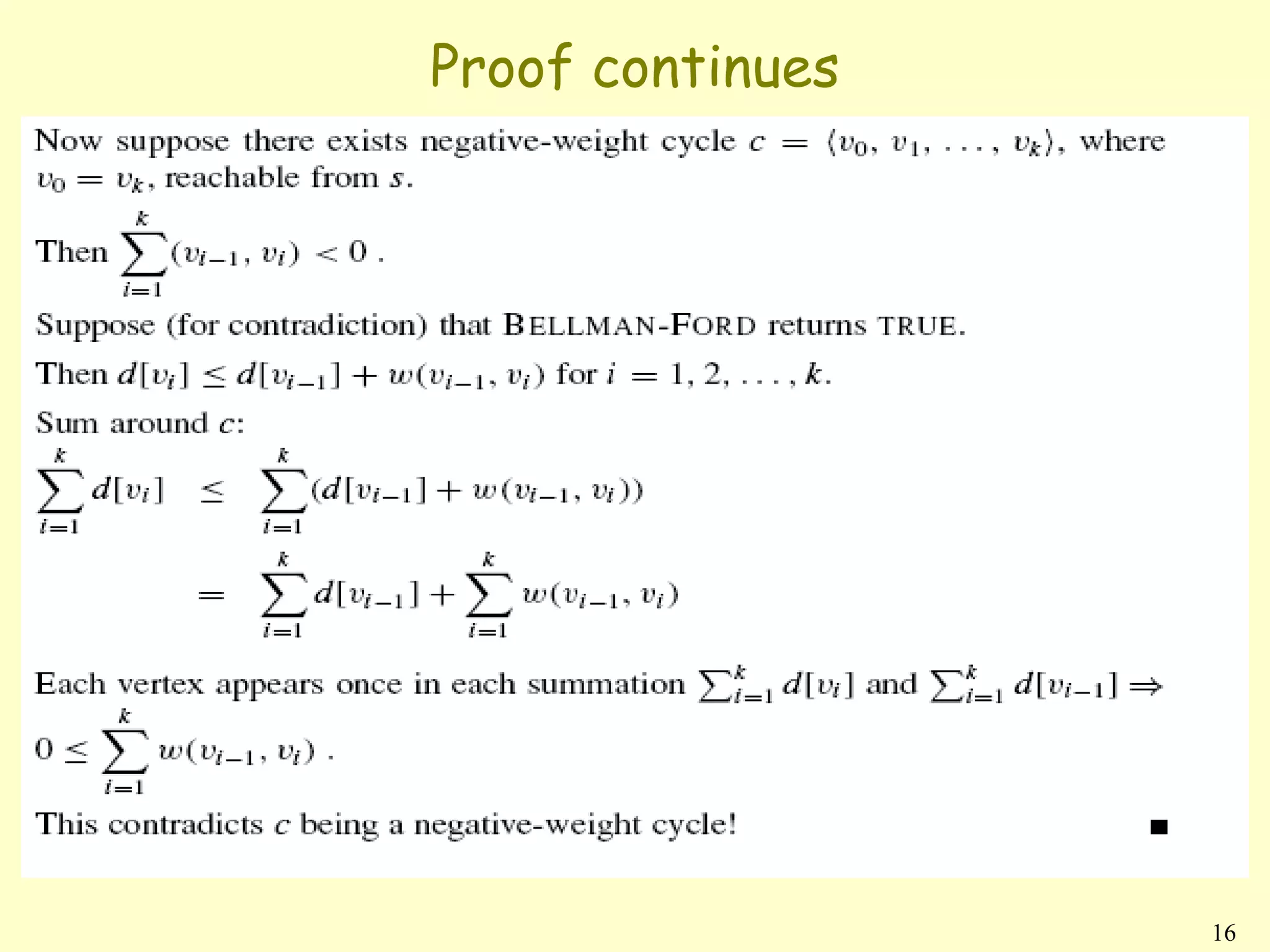

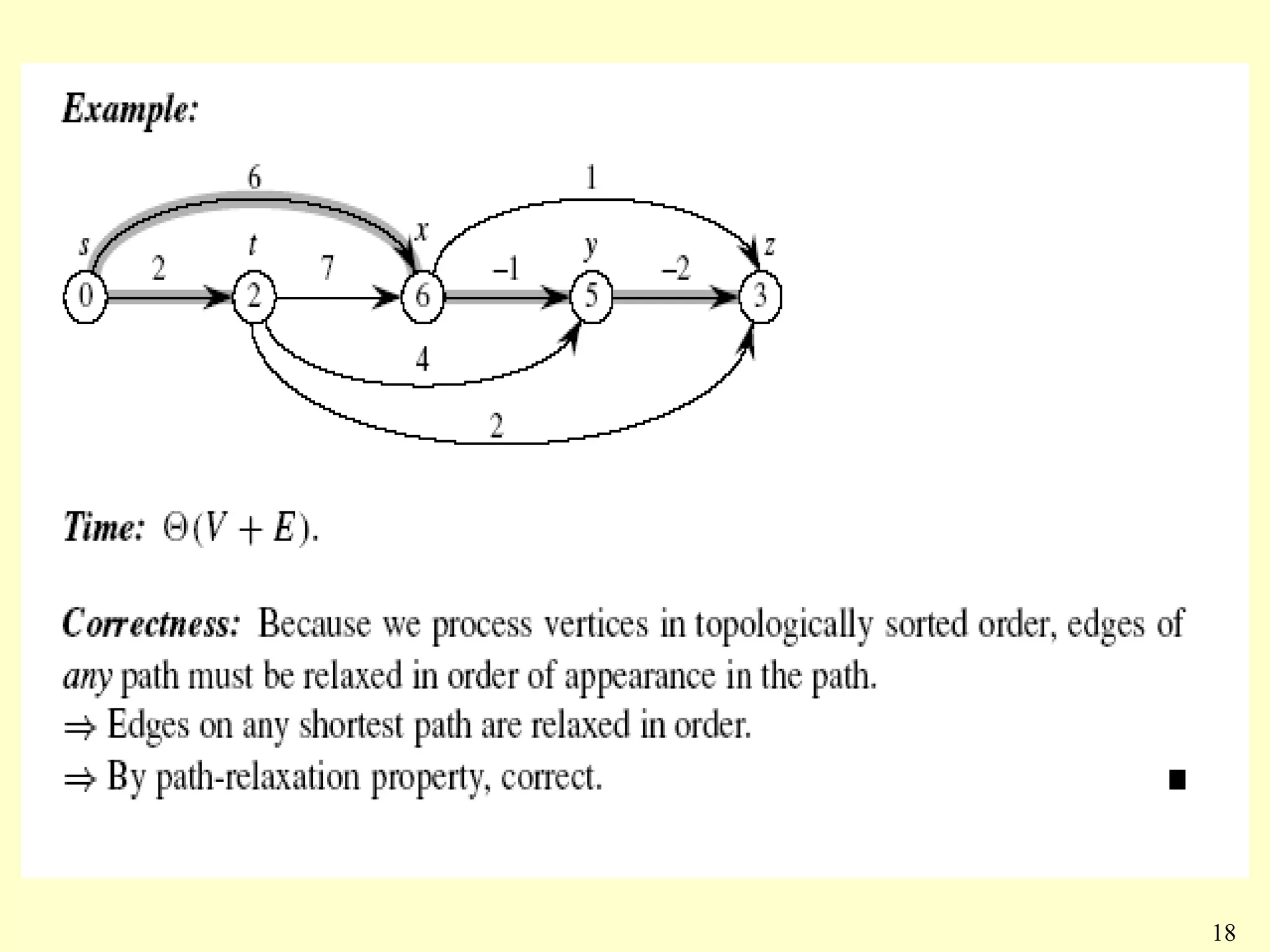

![Single-source shortest paths in a directed

acyclic graph

DAG-SHORTEST-PATHS(V, E, w, s)

{

topologically sort the vertices

INIT-SINGLE-SOURCE(V, s)

for each vertex u, in topologically order

for each vertex v in Adj[u]

RELAX(u, v, w)

}

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lect14-120617042852-phpapp02/75/Inroduction_To_Algorithms_Lect14-17-2048.jpg)

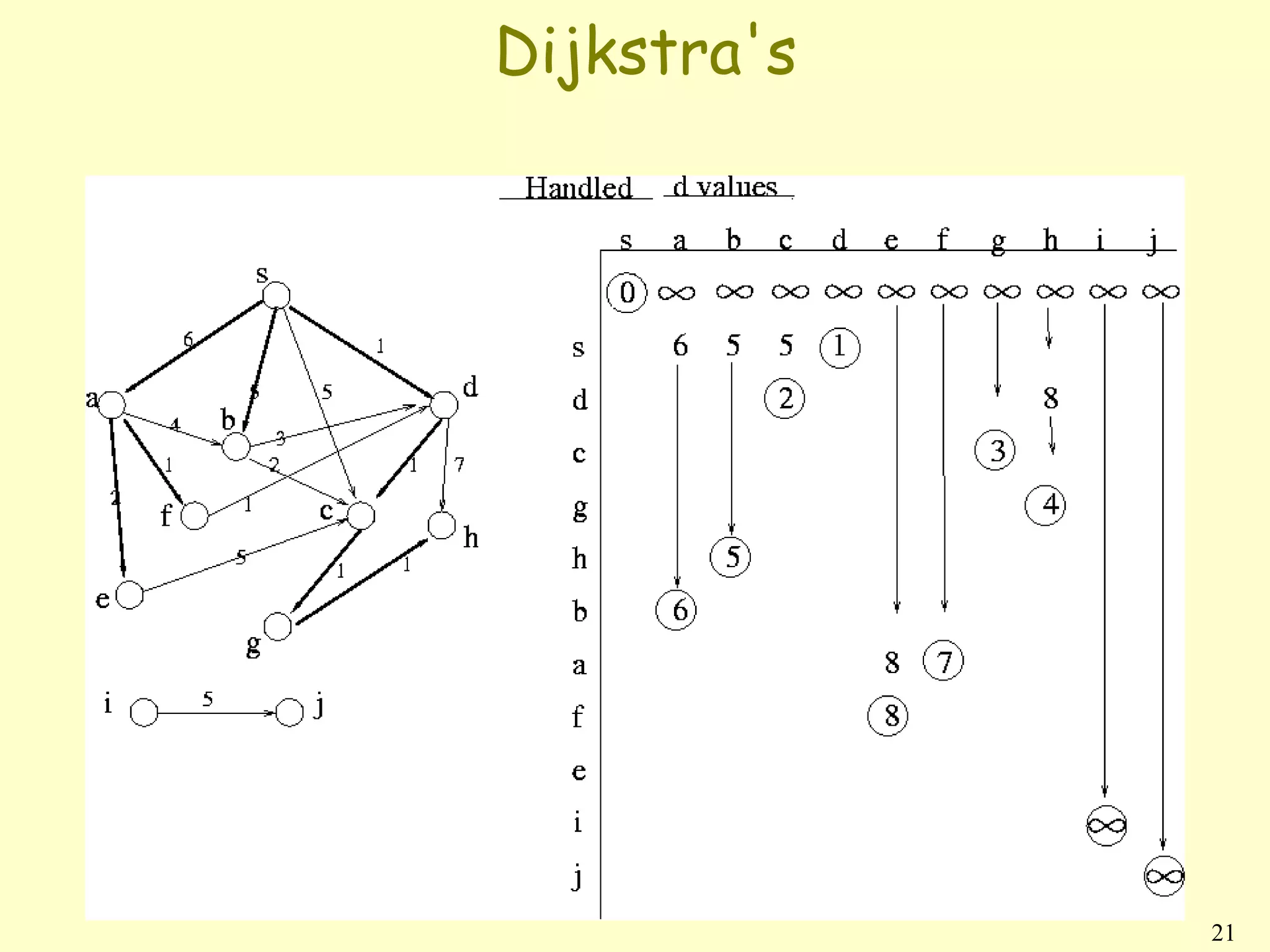

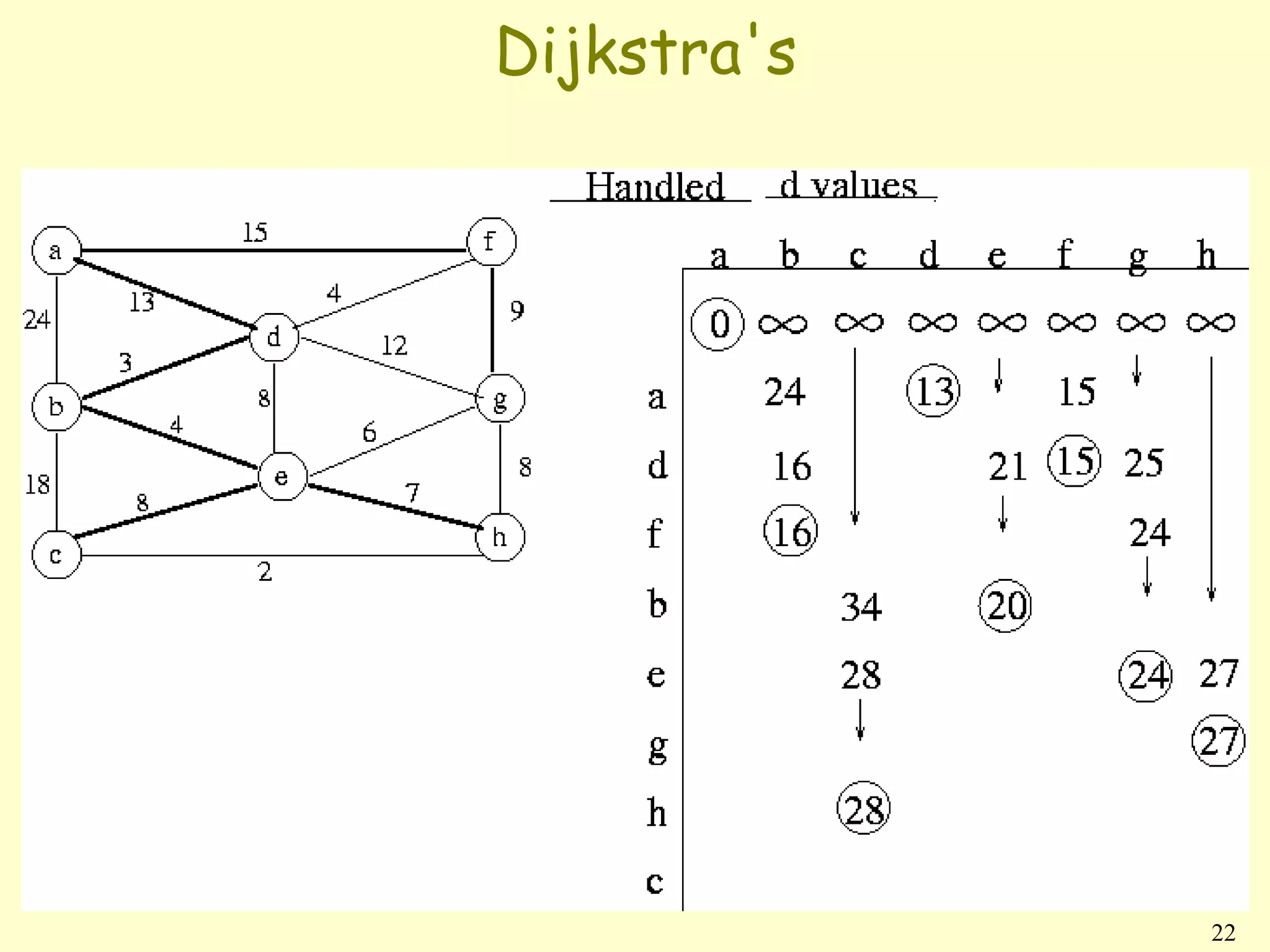

![Dijkstra’s algorithm

• No negative-weight edges.

• Essentially a weighted version of breadth-

first search.

• Instead of a FIFO queue, uses a priority

queue.

• Keys are shortest-path weights (d[v]).

• Have two sets of vertices:

S = vertices whose final shortest-path

weights are determined,

Q = priority queue = (was V − S. not

anymore)

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lect14-120617042852-phpapp02/75/Inroduction_To_Algorithms_Lect14-19-2048.jpg)

![Dijkstra algorithm

DIJKSTRA(V, E, w, s){

INIT-SINGLE-SOURCE(V, s)

Q←s

while Q = ∅{

u ← EXTRACT-MIN(Q)

for each vertex v in Adj [u]{

if (d[v] == infinity){

RELAX(u,v,w); (d[v]=d[u]+w[u,v])

enqueue(v,Q)

}

elseif(v inside Q)

RELAX(u,v,w);

change priority(Q,v);

}

} 20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lect14-120617042852-phpapp02/75/Inroduction_To_Algorithms_Lect14-20-2048.jpg)