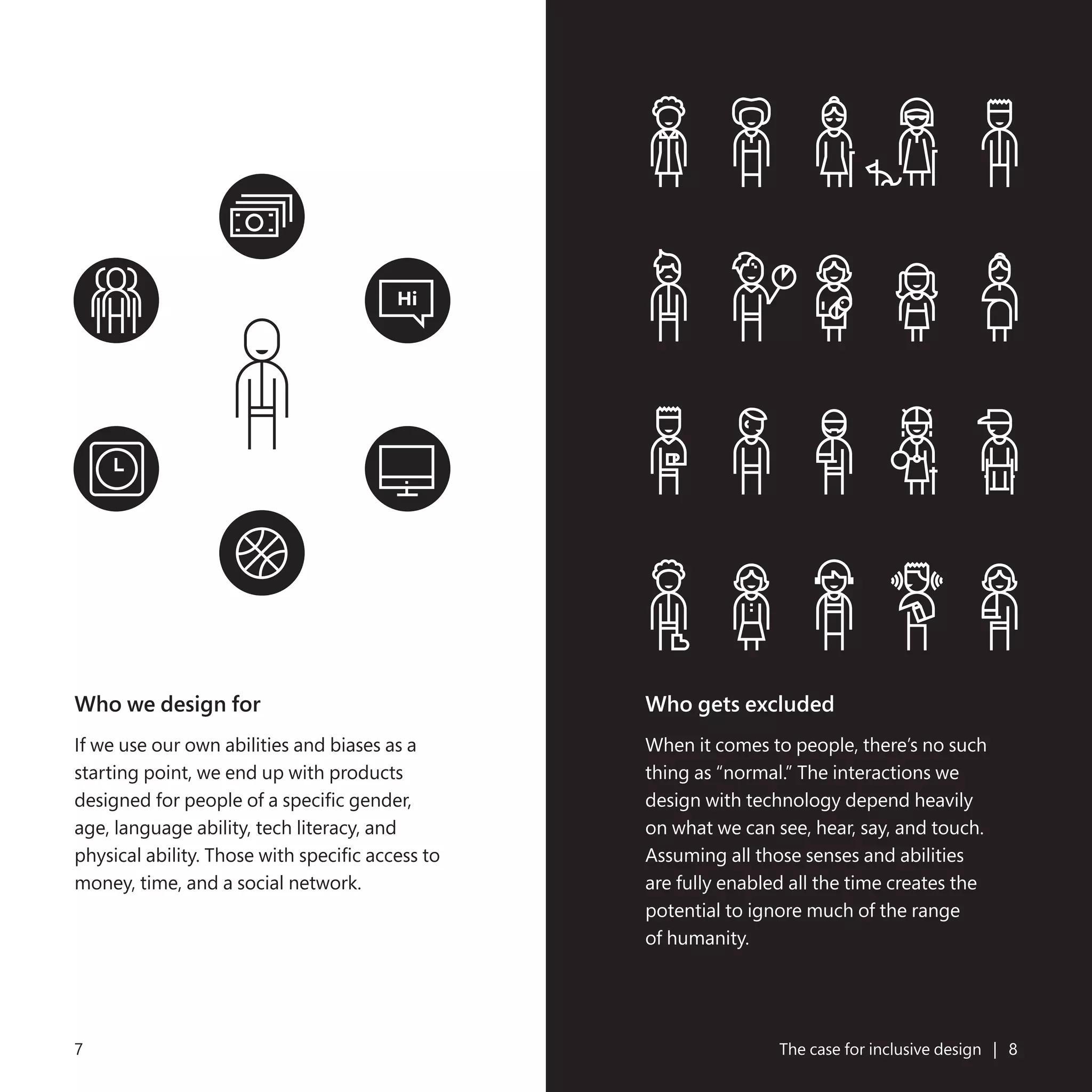

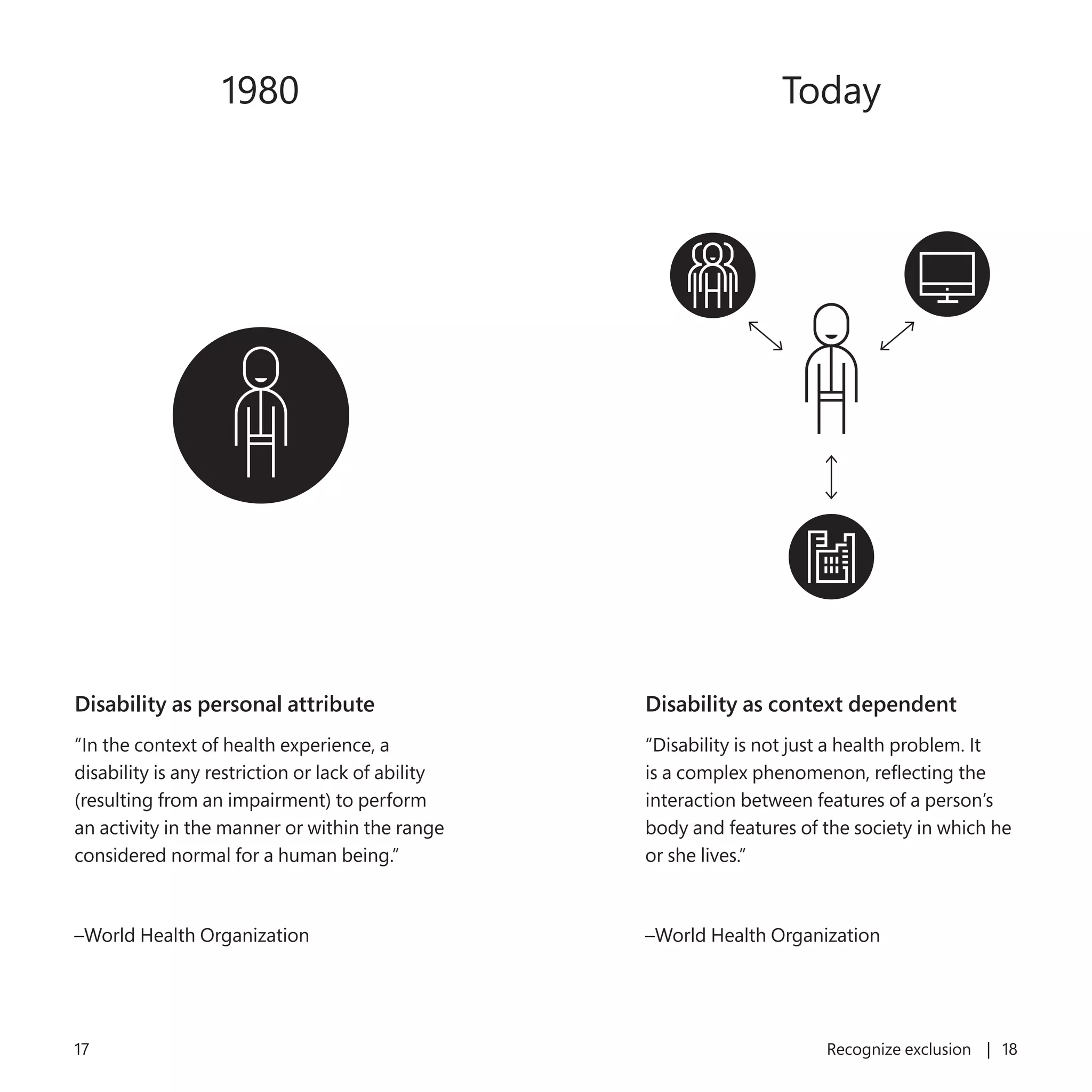

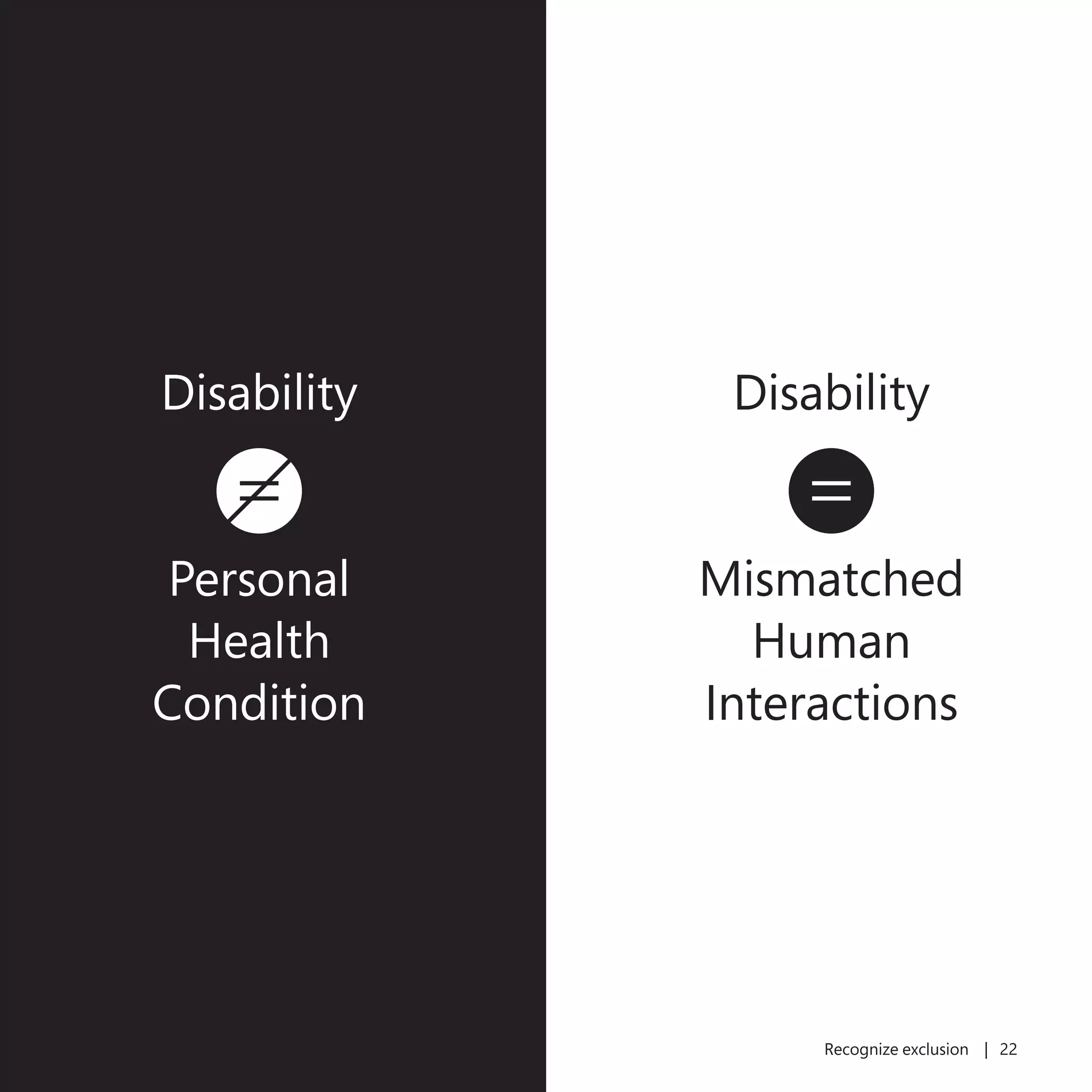

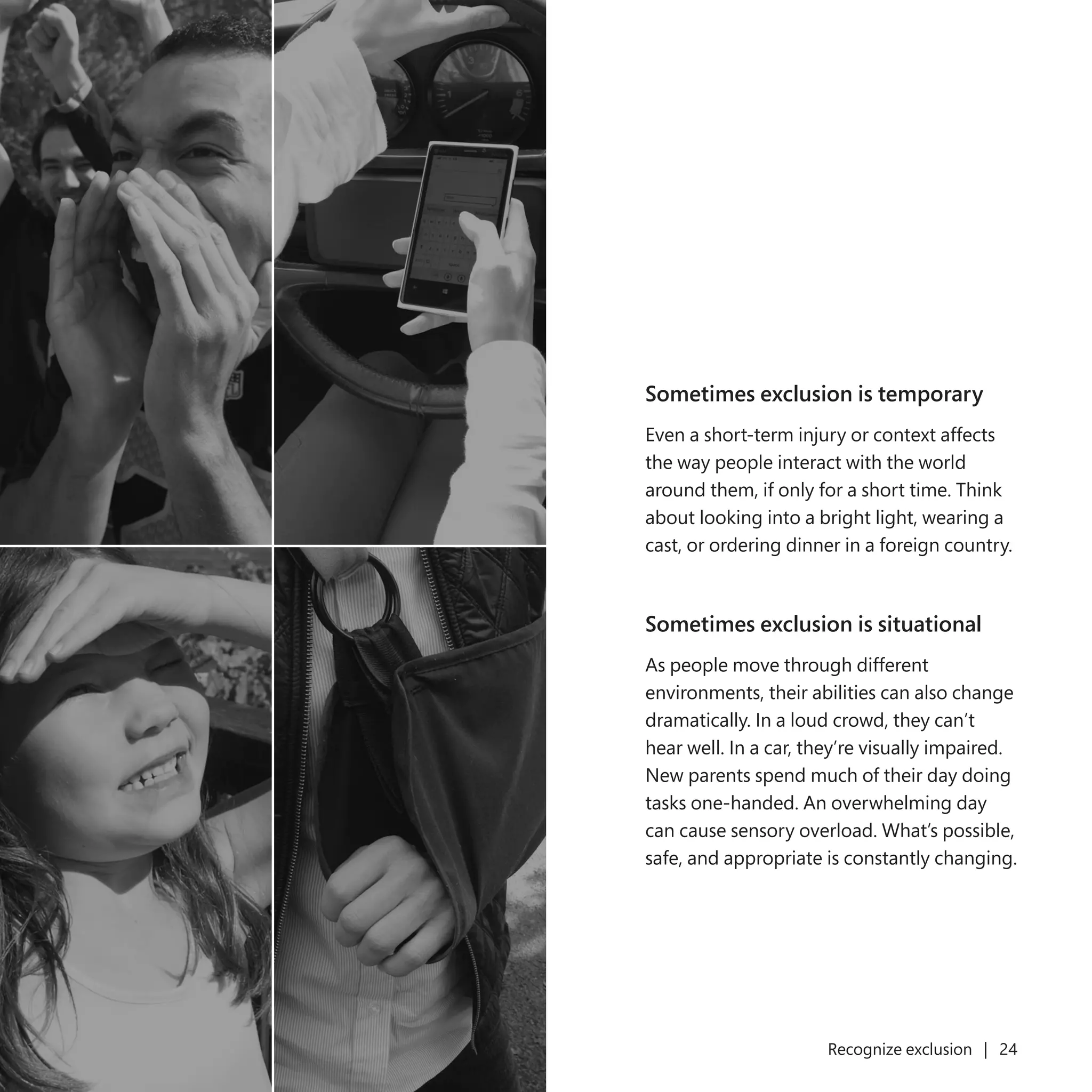

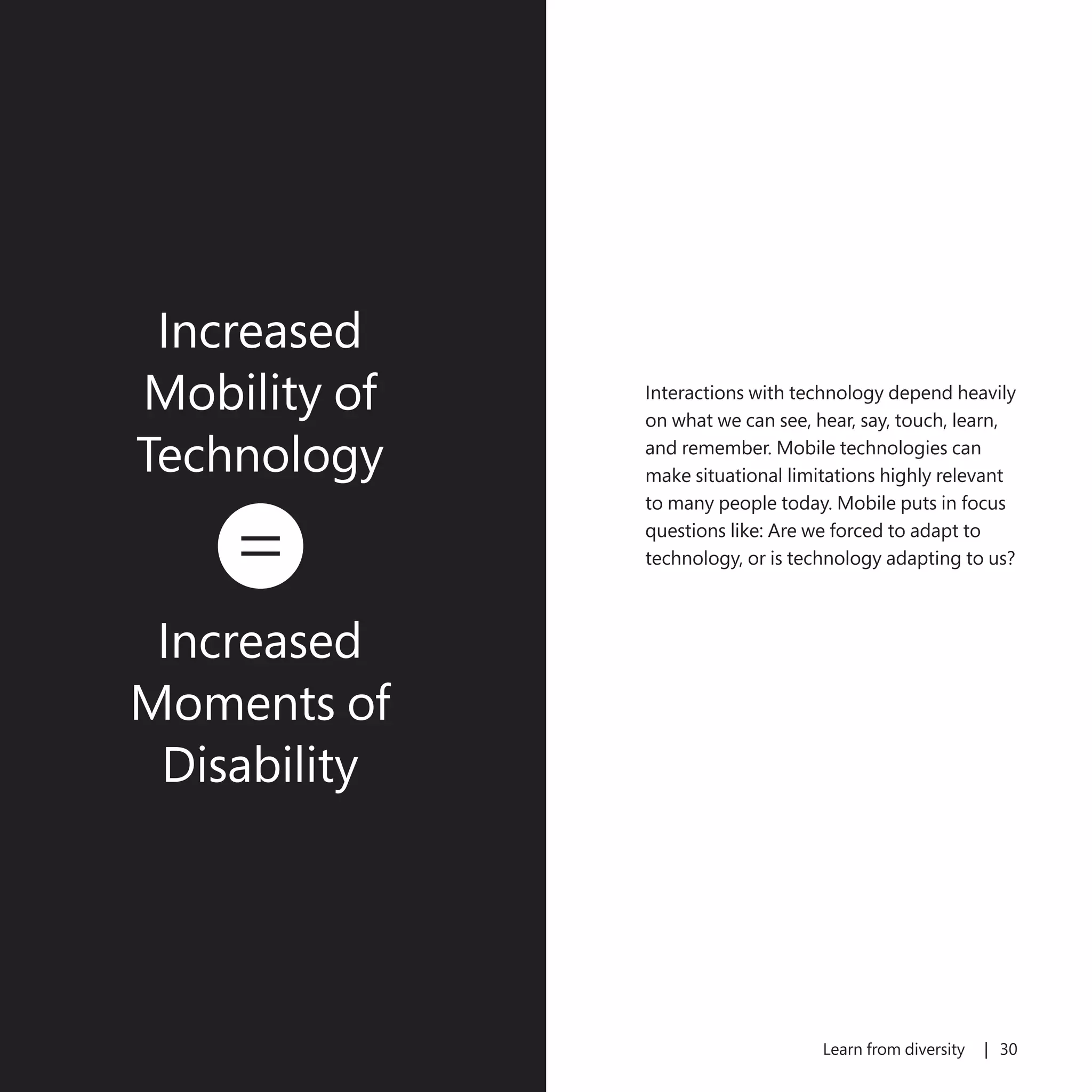

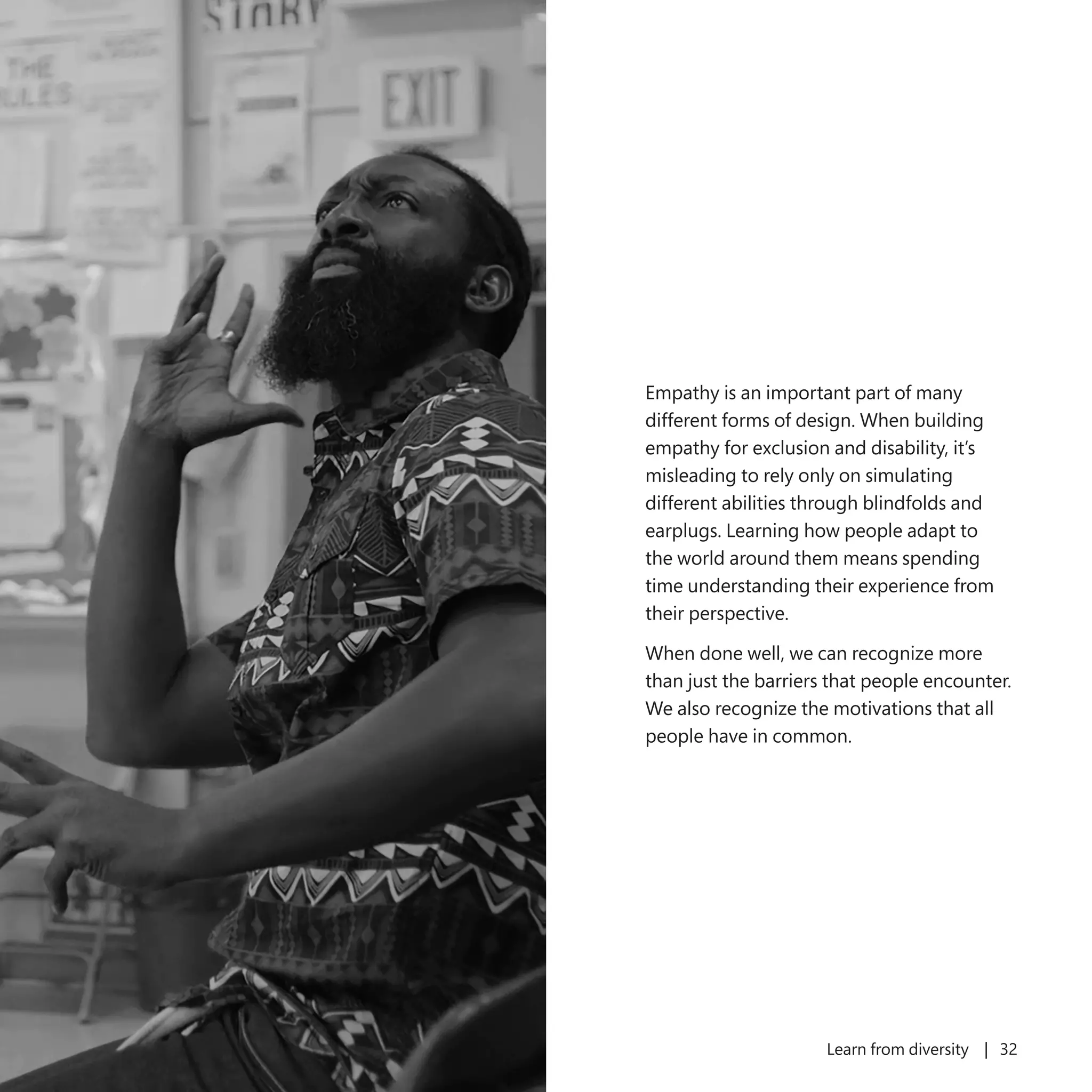

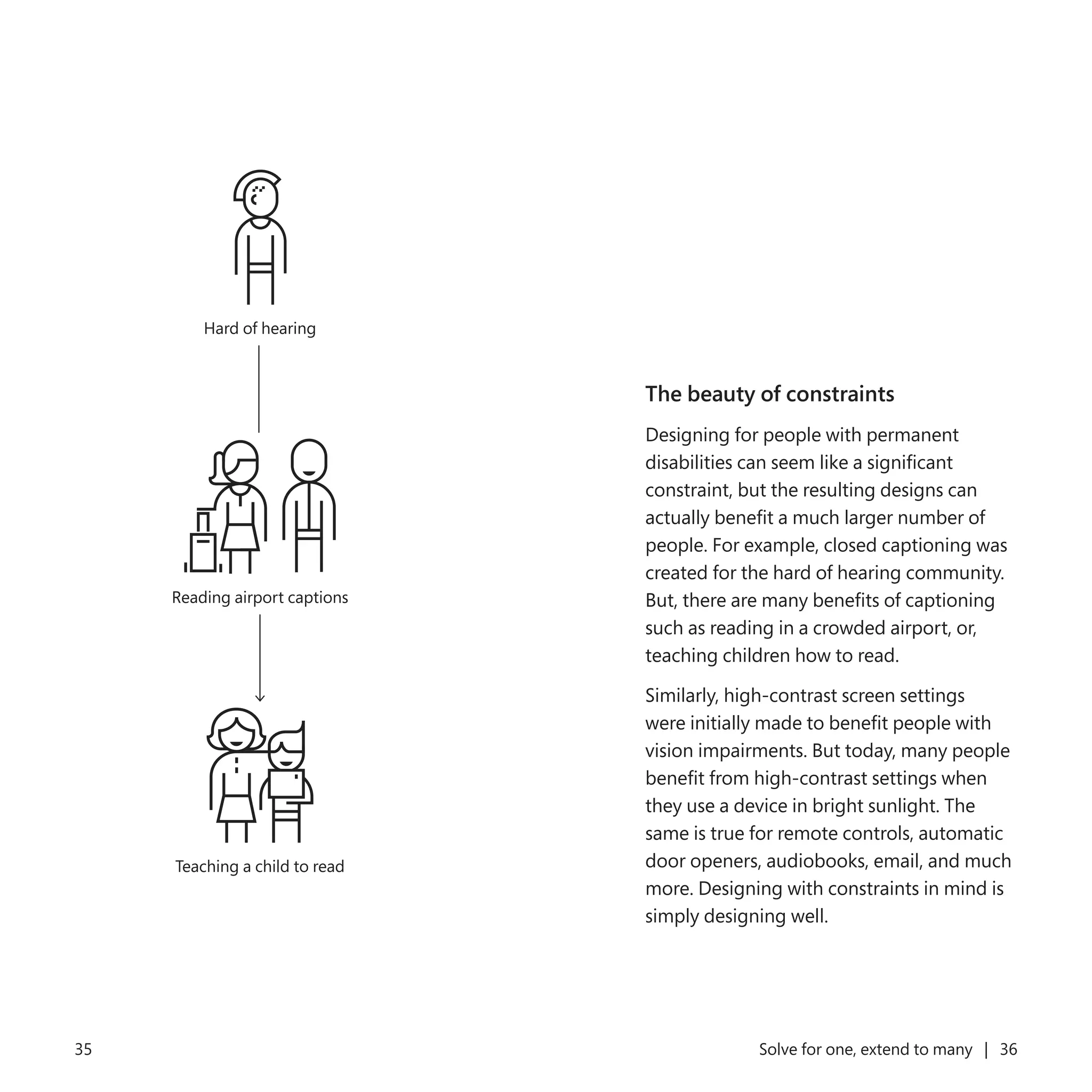

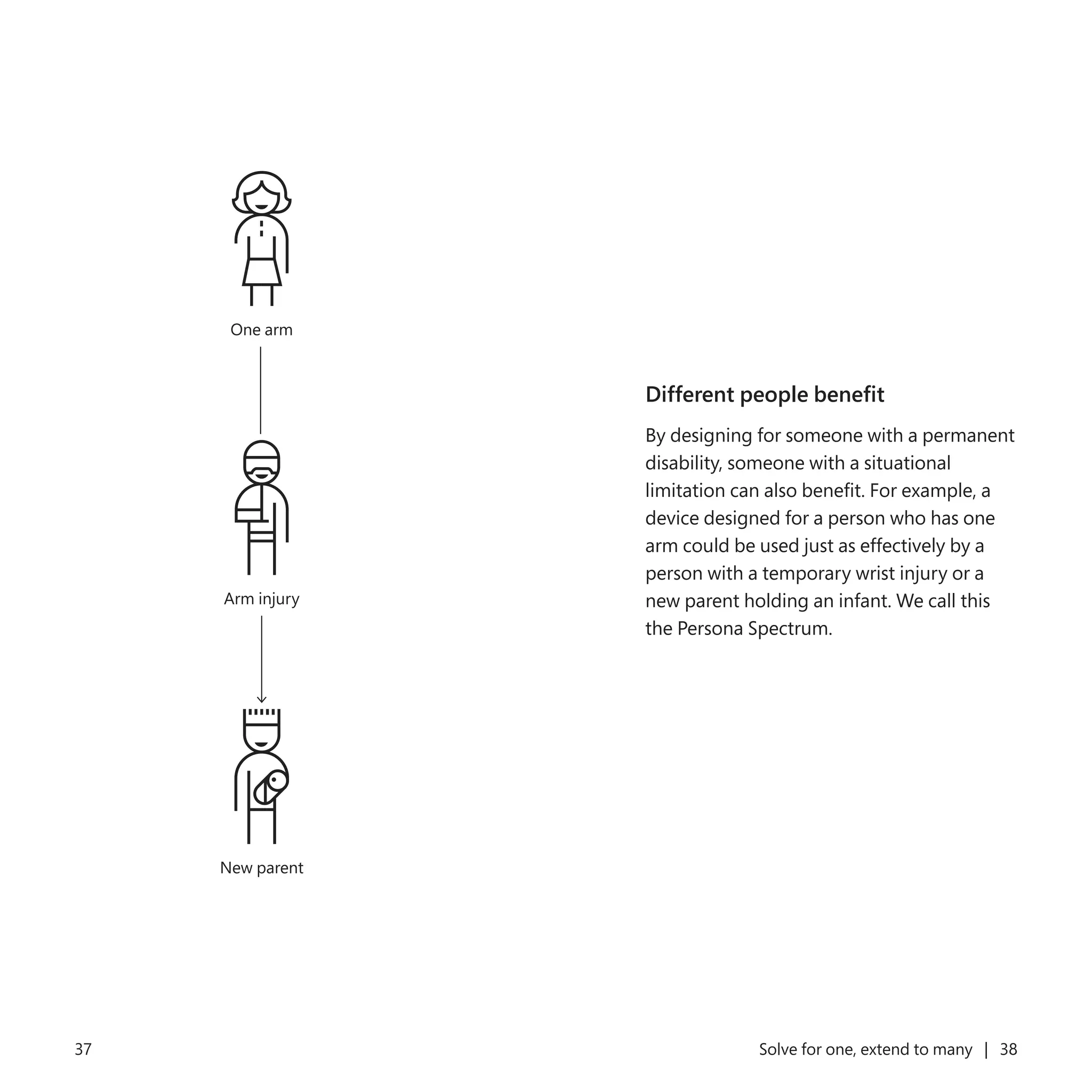

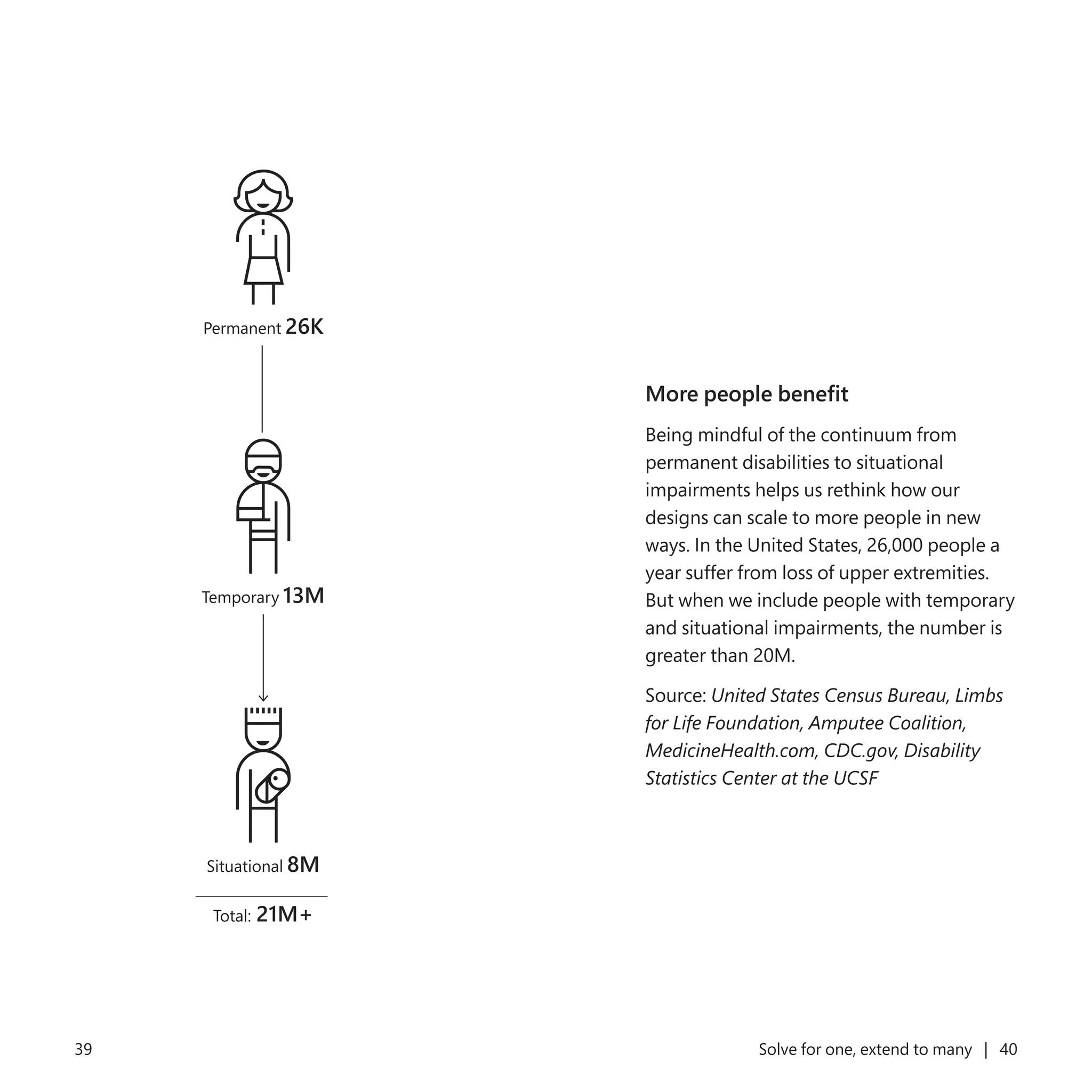

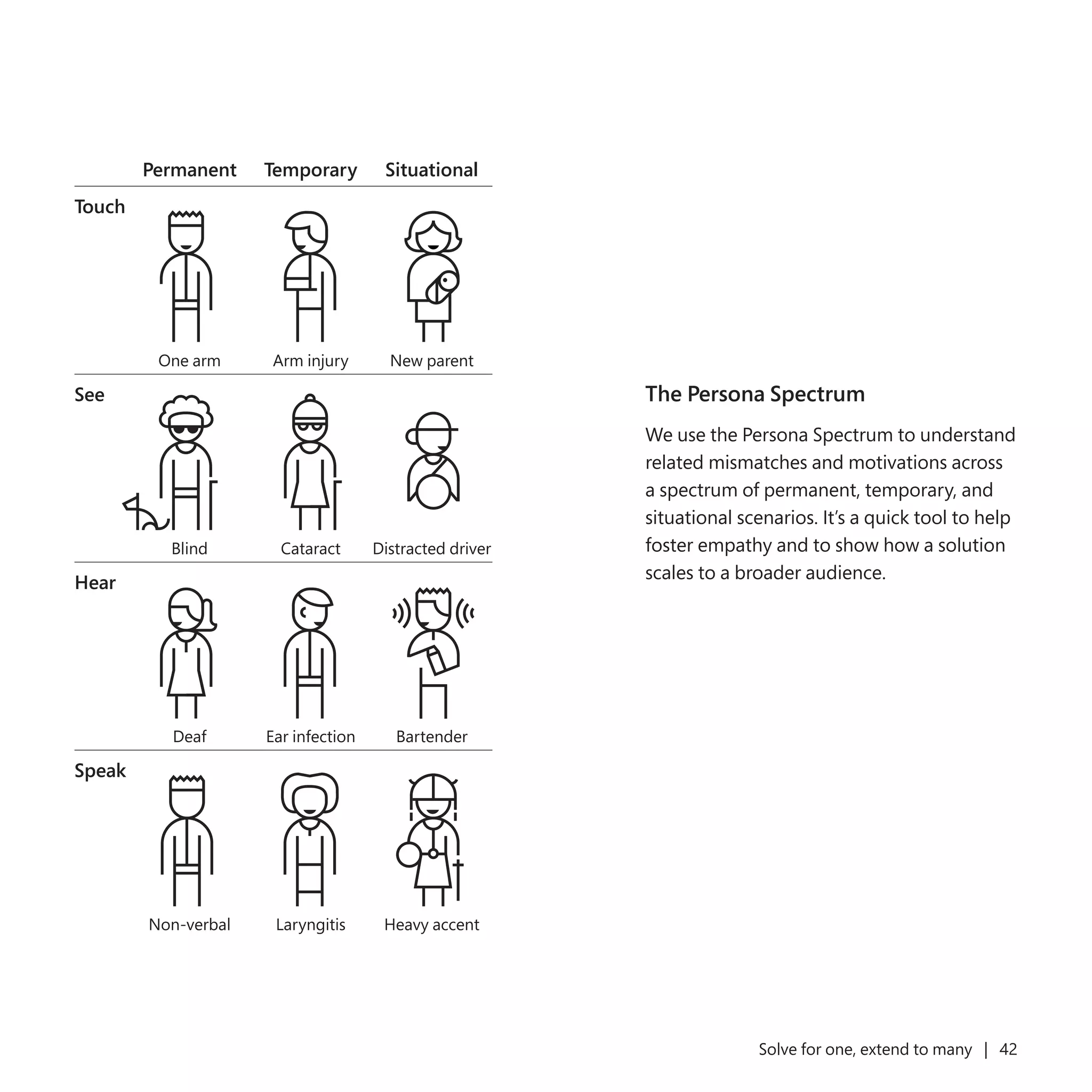

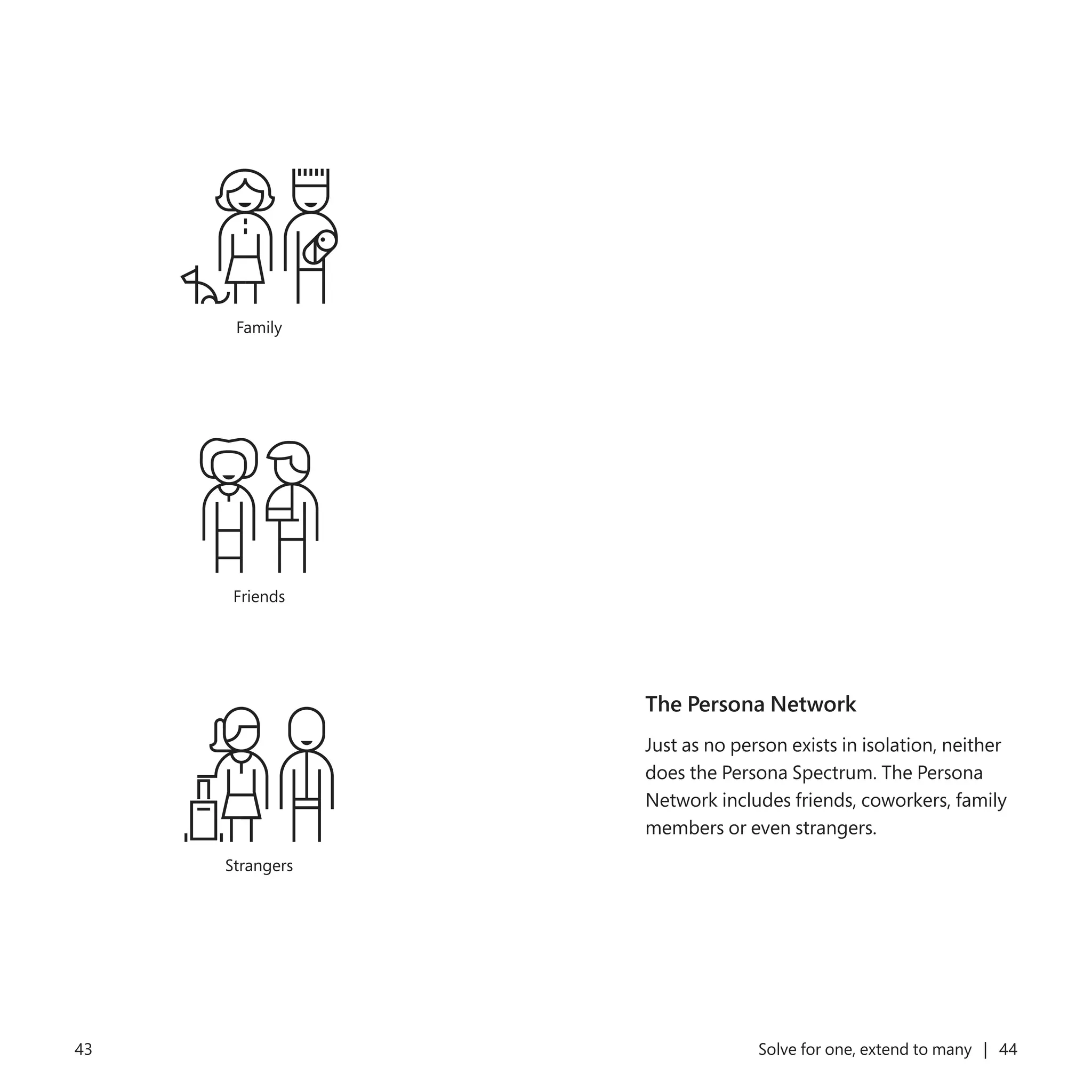

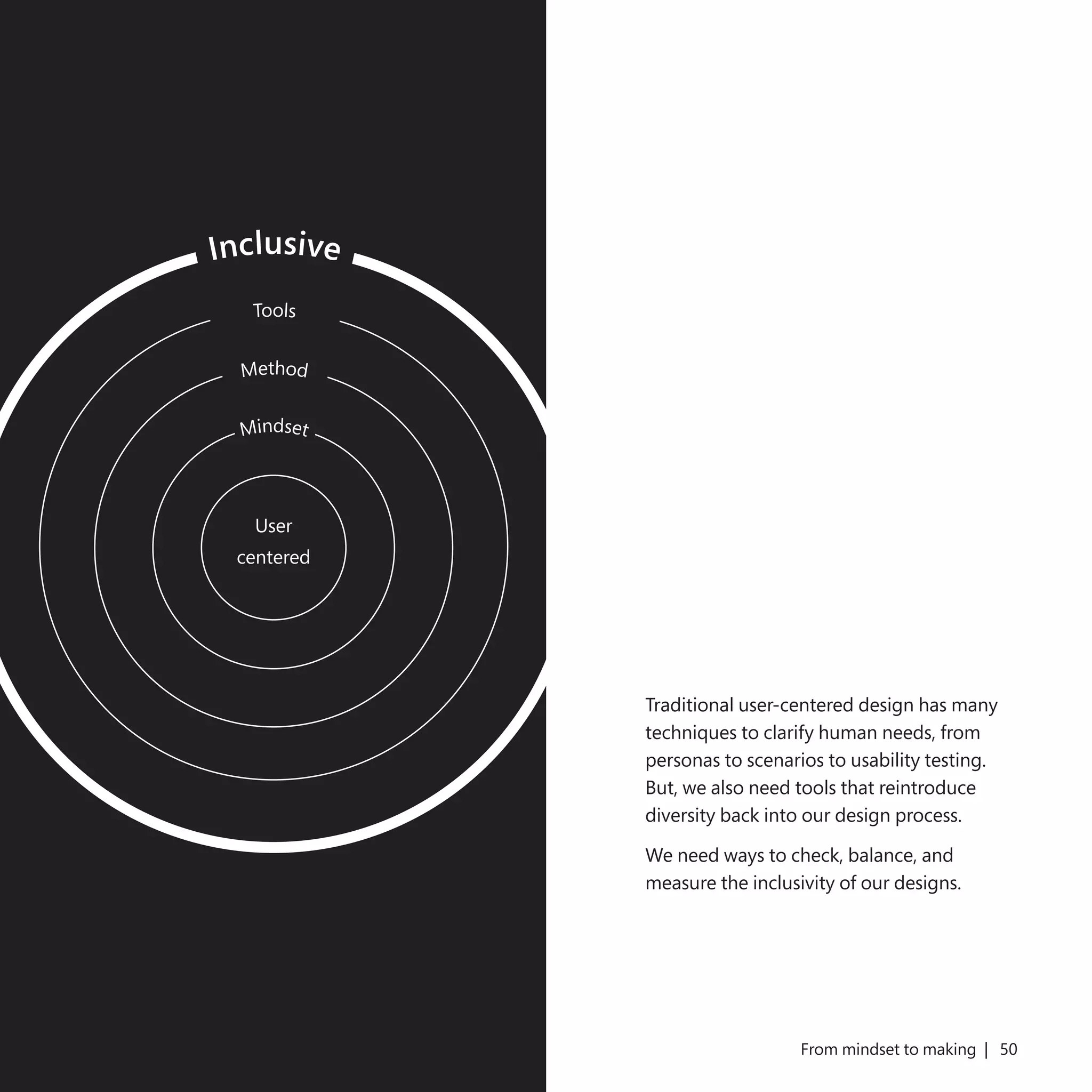

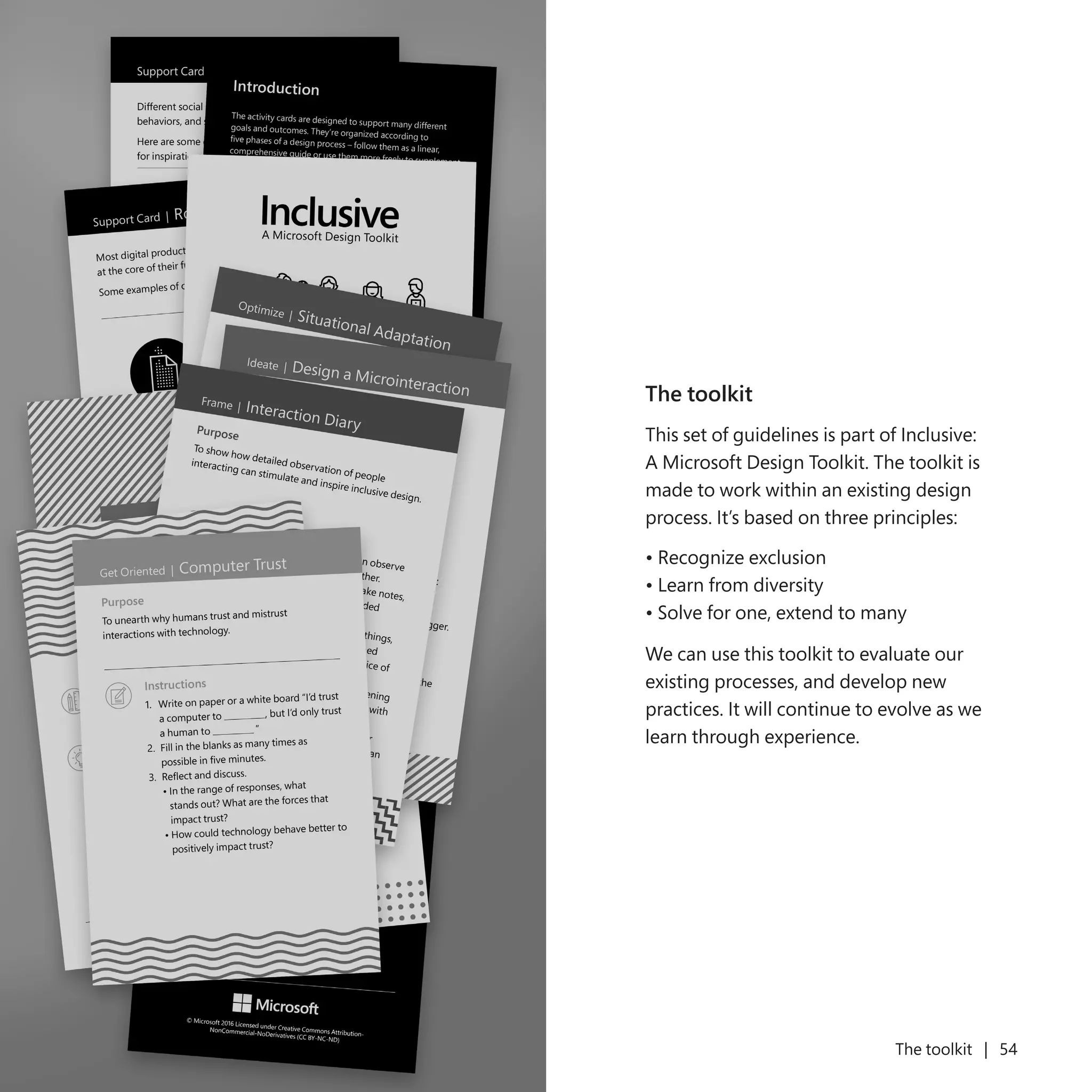

The document outlines Microsoft's guidelines for inclusive design, emphasizing the importance of creating products that are accessible and usable for the diverse range of human abilities. It discusses key principles such as recognizing exclusion, learning from diversity, and solving for one to benefit many, highlighting how design can either lower or raise participation barriers in society. The toolkit provides actionable steps for designers to implement inclusive practices and improve their design processes for greater inclusivity.