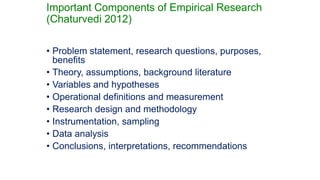

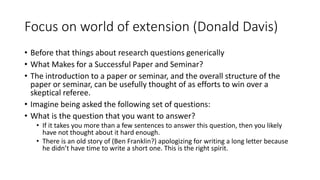

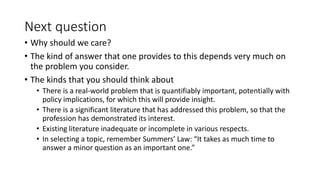

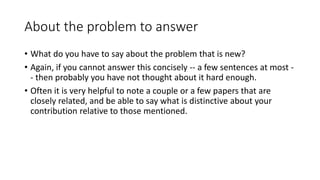

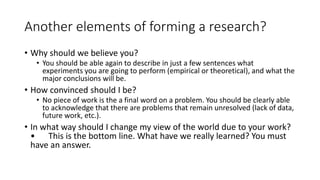

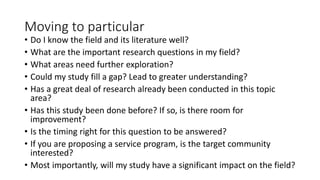

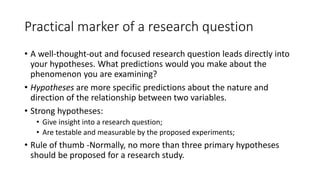

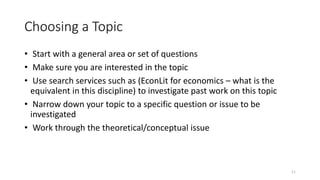

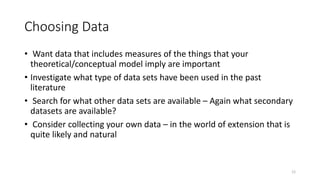

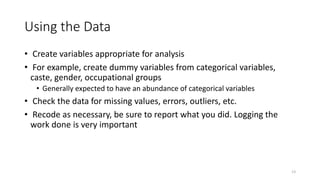

The document outlines essential components of empirical research, focusing on formulating research questions, hypotheses, and the importance of a clear problem statement. It emphasizes the need for a well-structured approach to conducting research, addressing issues such as data selection, model estimation, and interpretation of results. Additionally, it highlights the significance of understanding existing literature and the necessity of presenting concise insights into the research's contributions and implications.