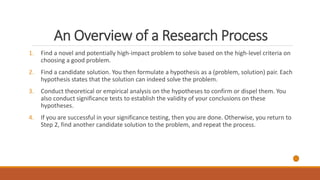

1. The document outlines the key steps in a research process including finding a problem, formulating hypotheses to solve the problem, testing hypotheses through theoretical or empirical analysis, and returning to find new solutions if testing is unsuccessful.

2. It discusses Jim Gray's criteria for high-impact research including having clear benefit, a simple statement, no obvious solution, testable progress, and the ability to break problems into smaller steps.

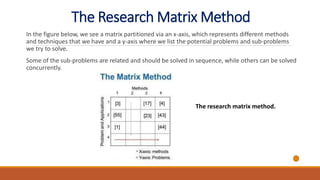

3. Common research methods like the research matrix method and carrying out experiments, statistical analysis, and domain explanations are explained. The role of researchers and differences between theoretical and empirical research are also summarized.

![BRANDING YOURSELF

Let us go horizontal first. This is when you have a good grasp on a significant and

high-impact sub problem, perhaps due to your fastidious experimentation and

examination of a particular problem at hand, or perhaps because you have

gained an important insight by reading many research papers and noticed a lack

of attention to a hidden gem.

Once you have a good understanding of the nature and complexity of the sub-

problem, you start asking the questions.

“Can method [x] be applied to this problem?” “What impact will be brought

forth if I succeed in applying method [x] to this problem?” and, “if method [x]

cannot be applied to this problem, what knowledge is gained in the field of

research?”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit2-rm-230924165534-bb5d11be/85/Unit2-RM-pptx-15-320.jpg)