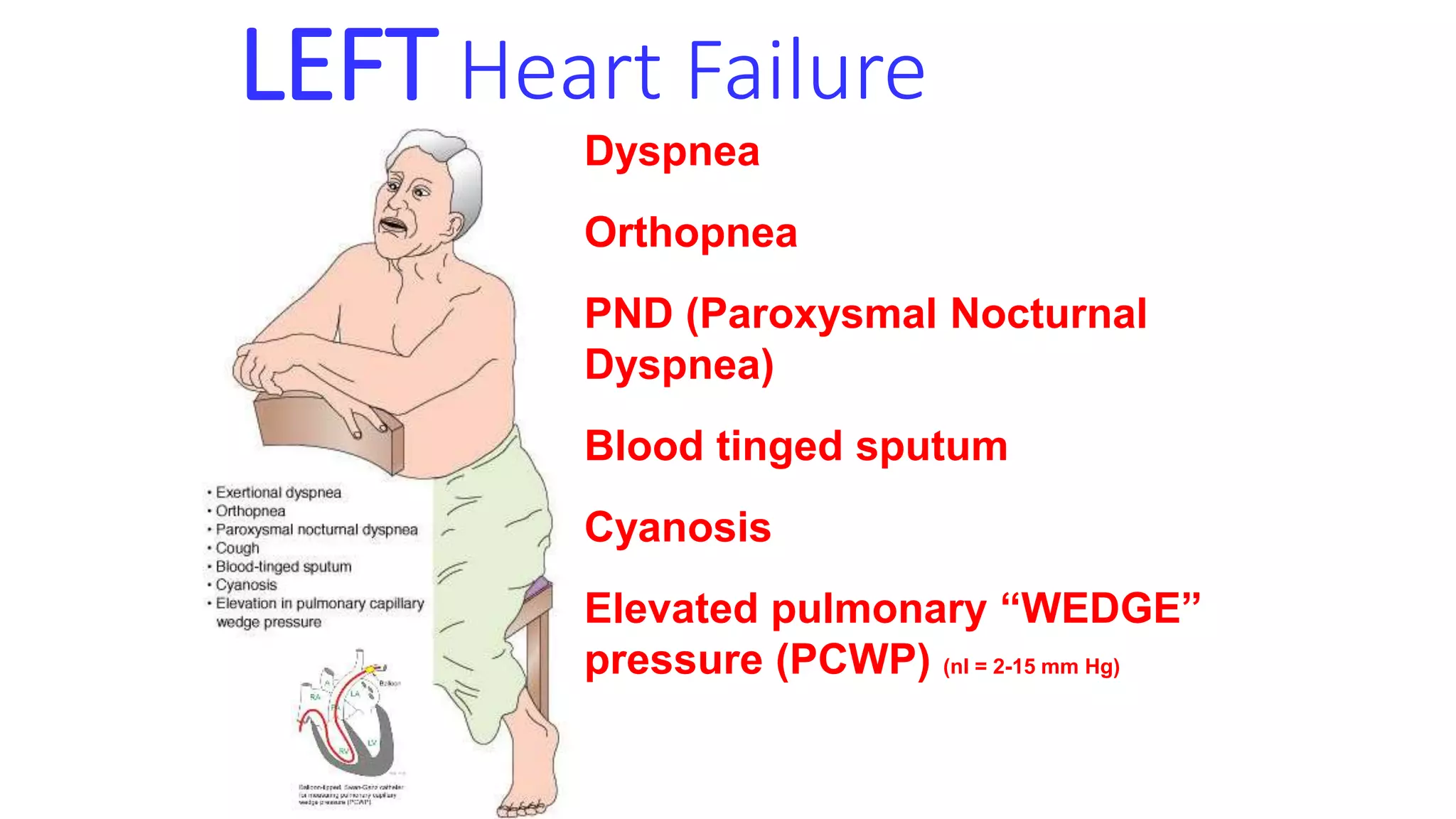

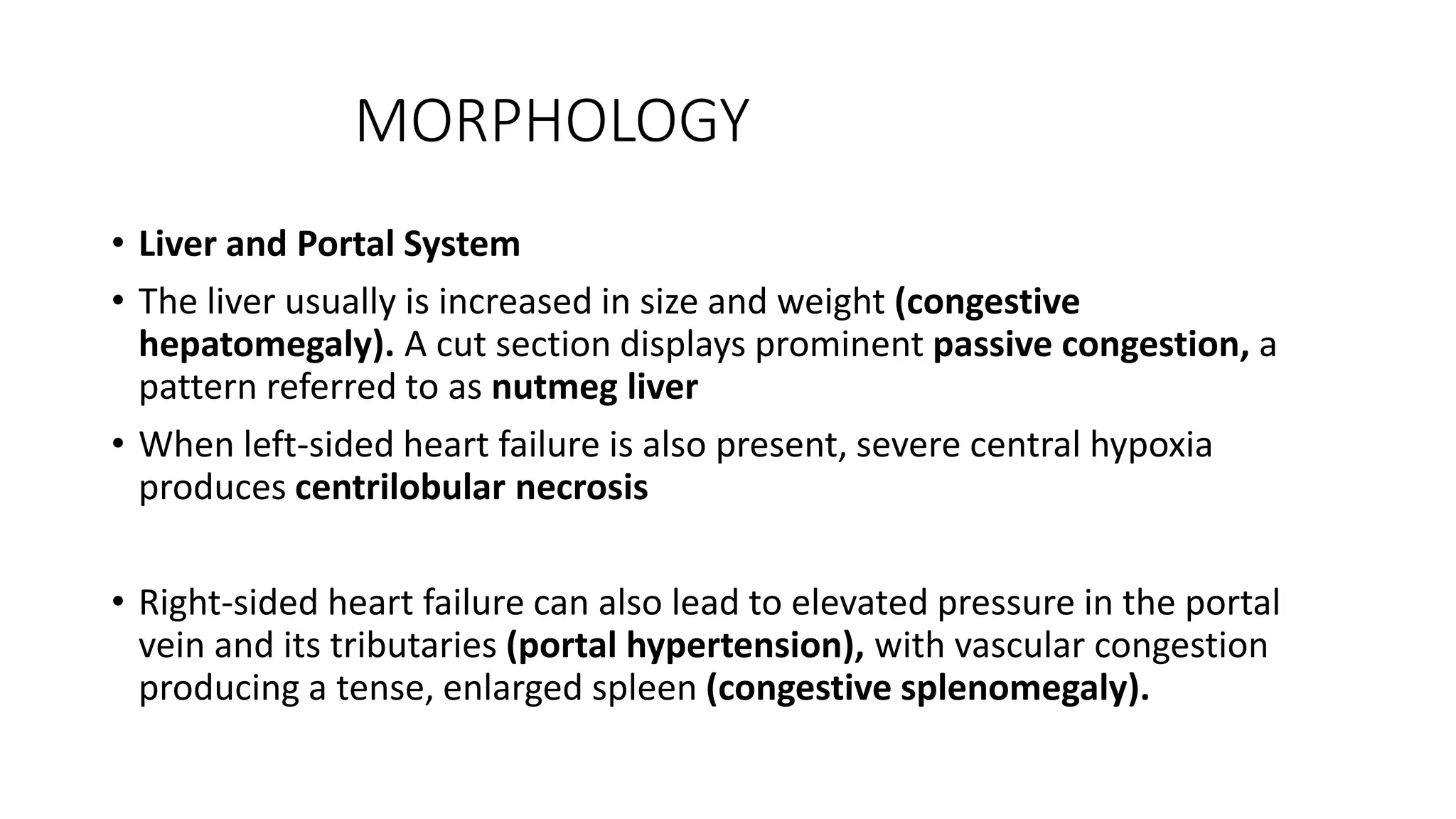

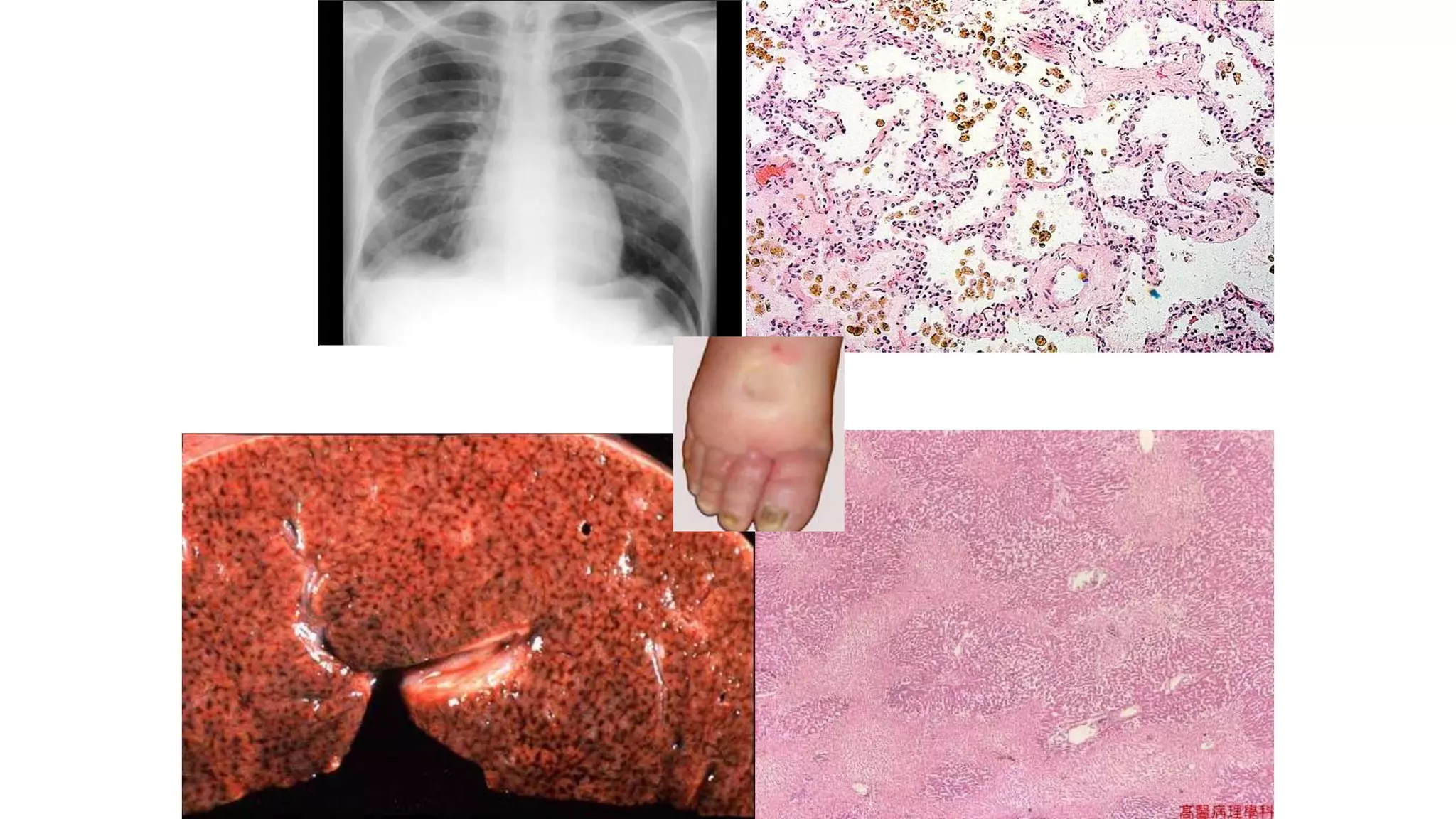

Heart failure occurs when the heart cannot pump enough blood to meet the body's needs. It can be caused by problems with either the left or right side of the heart. Common causes include heart disease and hypertension. Symptoms depend on whether the left or right side is affected. The left side controls blood flow to the lungs, so left heart failure causes shortness of breath and coughing up blood. The right side controls blood returning from the body, so right heart failure causes fatigue, leg swelling and liver/kidney congestion. Over time the heart tries to compensate through enlargement but eventually decompensates leading to further symptoms.