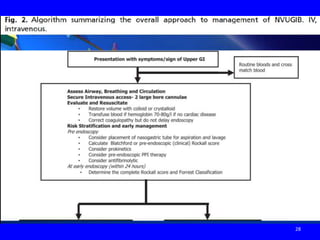

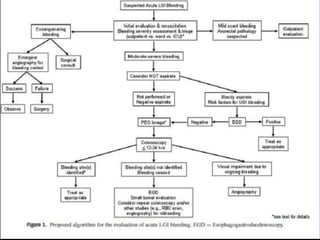

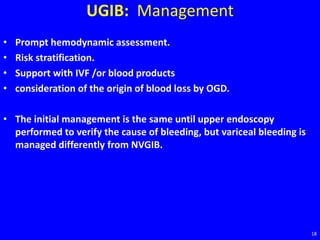

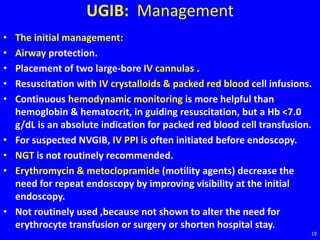

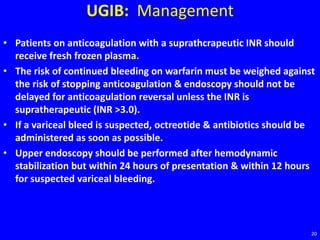

- The document provides an overview of gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB), including causes, evaluation, and management.

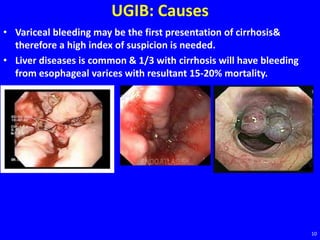

- Common causes of upper GI bleeding (UGIB) include peptic ulcer disease, esophageal varices, esophagitis, and malignancy. Evaluation involves history, physical exam, and laboratory tests to assess severity and risk of rebleeding.

- Initial management of UGIB includes IV fluids, blood transfusions if needed, and upper endoscopy within 24 hours to identify the source of bleeding and guide treatment. Management depends on the cause and risk of rebleeding.

![UGIB: Management

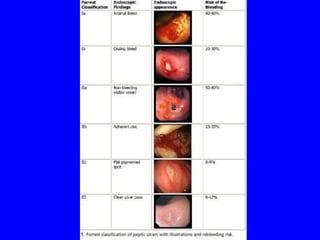

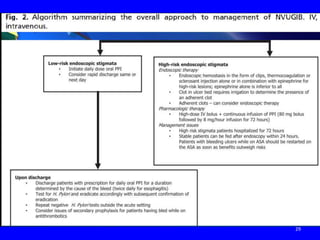

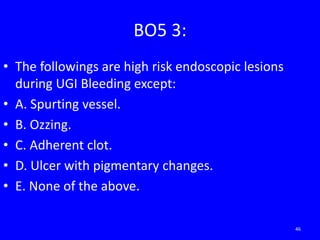

• Endoscopic trt of a bleeding ulcer depends on the ulcer

characteristics, an important predictors of recurrent bleeding.

• Low-risk stigmata: (a clean-based ulcer [rebleeding risk with

medical therapy 3-5%] or a nonprotuberant pigmented spot in an

ulcer bed [rebleeding risk with medical therapy 5-10%]) can be fed

within 24 hours,should receive oral PPI therapy& can undergo early

hospital discharge.

21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/git4thgib-150318154552-conversion-gate01/85/GIT-Bleeding-for-4th-year-21-320.jpg)

![UGIB: Management

• High risk stigmata:

• Ulcers with adherent clots (rebleeding risk with medical trt 25-30%)

can be irrigated to disrupt the clot& endoscopic trt provided after.

• Patients with high-risk stigmata (active arterial spurting [rebleeding

risk with medical therapy 80-90%] or a nonbleeding visible vessel in

an ulcer base [rebleeding risk with medical therapy 40-50%]) should

be treated with epinephrine injection+ one of" the following:

• Hemoclips, thermocoagulation, or a sclerosant .

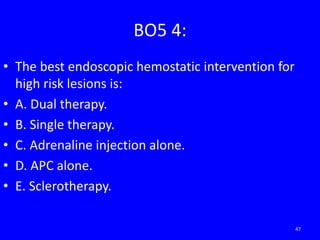

• Duration of PPI depends on the underlying cause of the ulcer

&future need for NSAIDs.

22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/git4thgib-150318154552-conversion-gate01/85/GIT-Bleeding-for-4th-year-22-320.jpg)