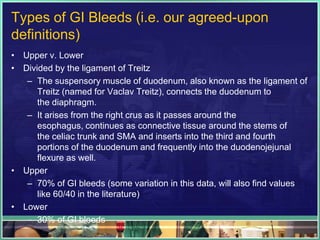

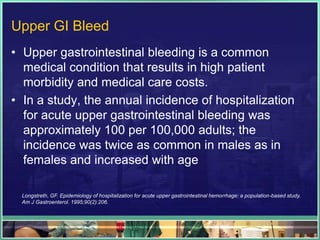

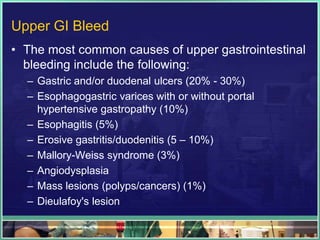

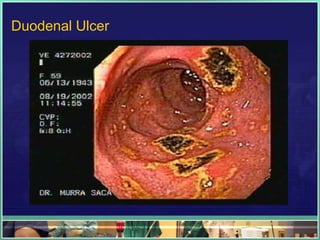

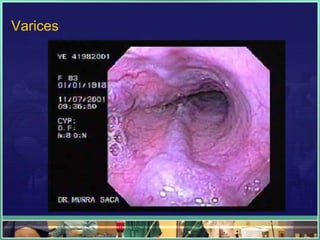

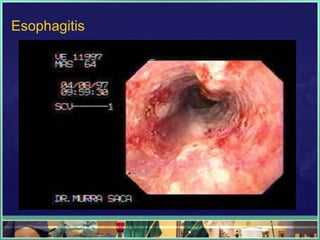

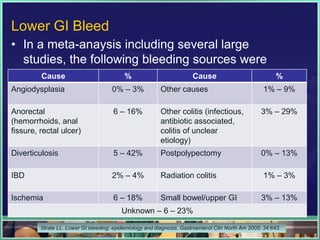

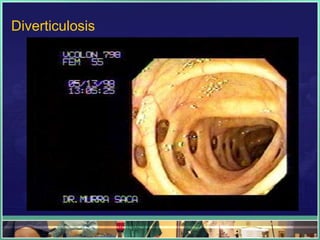

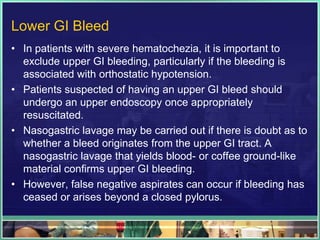

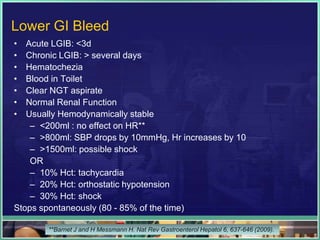

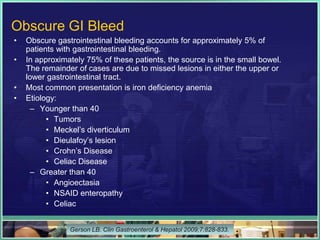

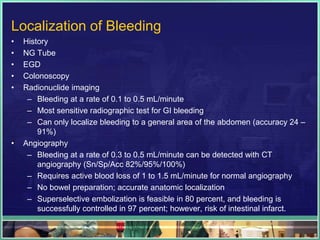

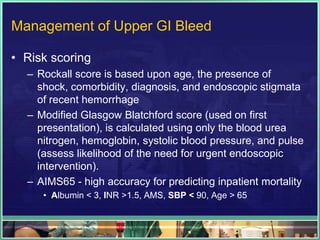

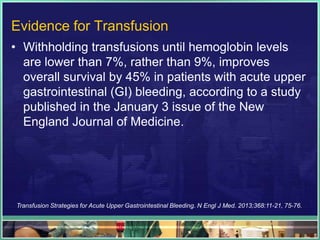

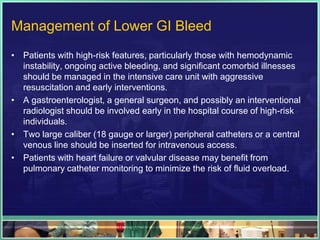

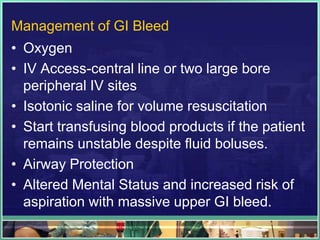

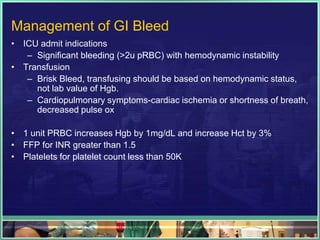

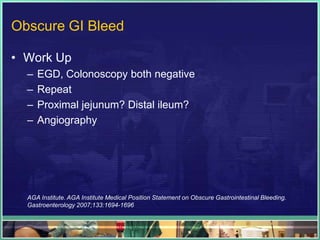

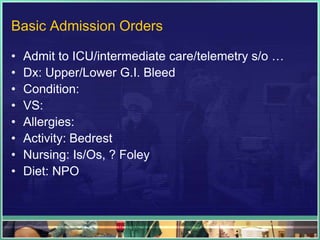

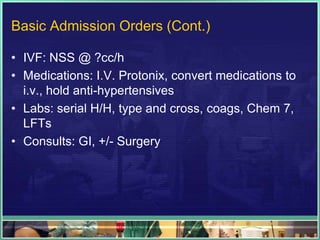

The document discusses gastrointestinal (GI) bleeds, including trends showing decreases in upper GI bleeds and increases in lower GI bleeds from 1998-2006. It covers the causes, classifications, presentations, and management of upper and lower GI bleeds, noting the most common causes are ulcers, varices, and diverticulosis. Risk scoring systems and initial management involves fluid resuscitation, transfusions based on stability rather than hemoglobin level, medications, and procedures to locate the source of bleeding.