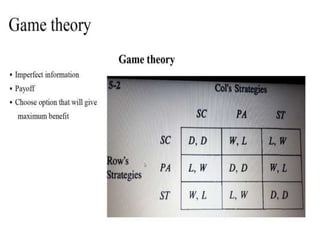

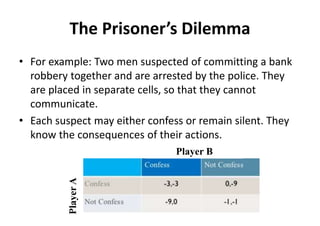

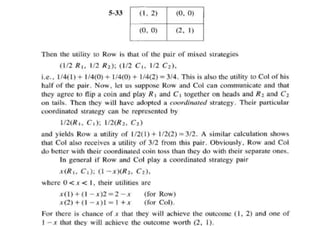

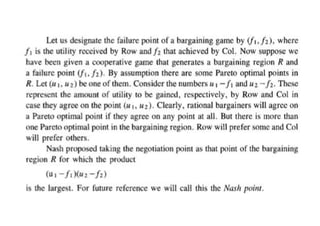

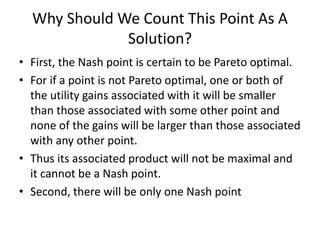

The document discusses game theory, focusing on non-zero-sum games where players' interests can overlap, emphasizing the complexity of cooperation without communication, exemplified by the prisoner's dilemma. It explores cooperative games where players may achieve better outcomes through coordination, highlighting the concept of Pareto optimal points and the challenges in identifying fair solutions. The text transitions to bargaining games, introducing Nash's solution as a guaranteed Pareto optimal point within the bargaining region.