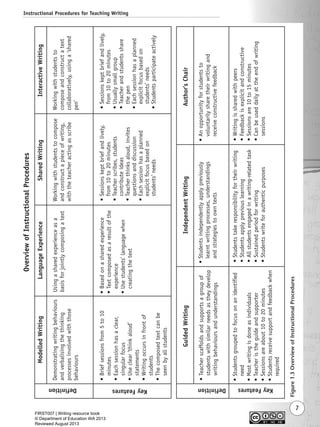

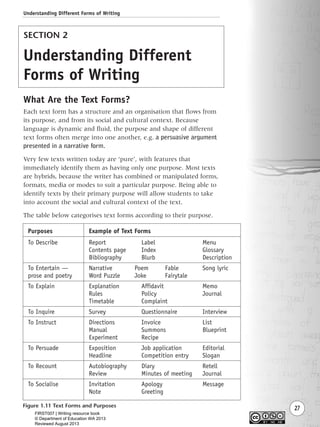

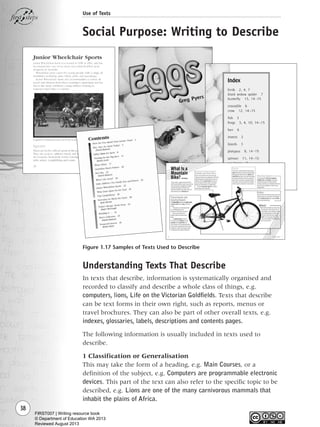

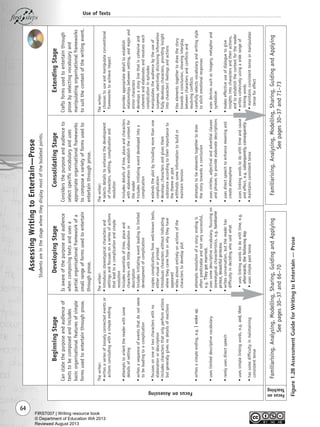

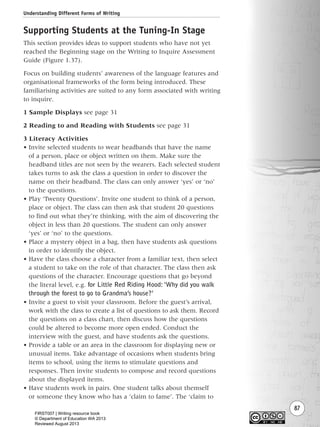

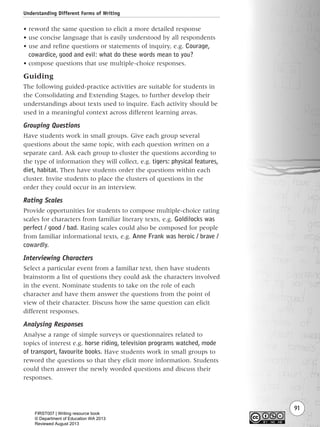

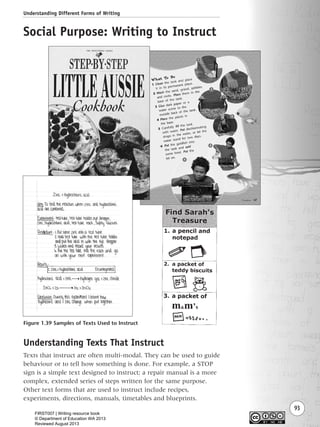

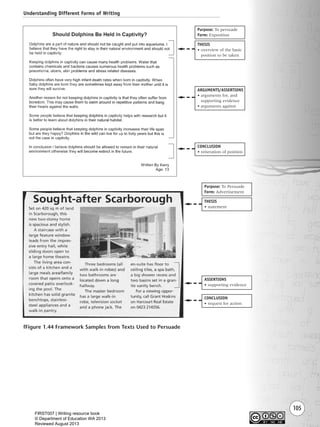

The First Steps Second Edition is a comprehensive resource for teachers aimed at improving literacy outcomes through structured assessment, teaching, and learning strategies. It includes practical texts and professional development courses, as well as a CD-ROM with essential teaching materials and assessment tools. The writing resource book specifically focuses on diverse instructional procedures to support the explicit teaching of various text forms and writing processes in a classroom setting.