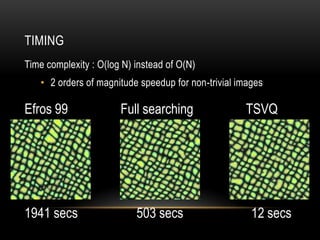

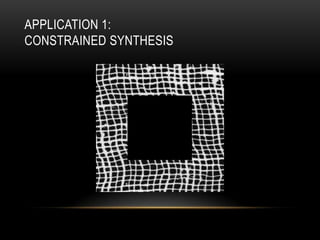

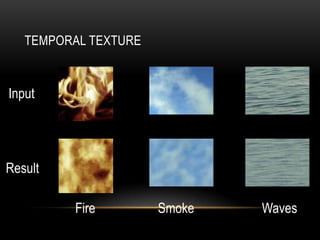

This document proposes a fast texture synthesis algorithm using tree-structured vector quantization (TSVQ) that can generate textures in 3 sentences or less that match an input texture efficiently. It models textures based on local spatial neighborhoods and uses an exhaustive search-based algorithm. By representing texture patches in a tree structure, it achieves a speedup of two orders of magnitude compared to previous methods, synthesizing textures in 12 seconds versus over 30 minutes for other algorithms. The method produces results that look like the input texture while being efficient and extensible to applications like image editing and temporal texture synthesis.