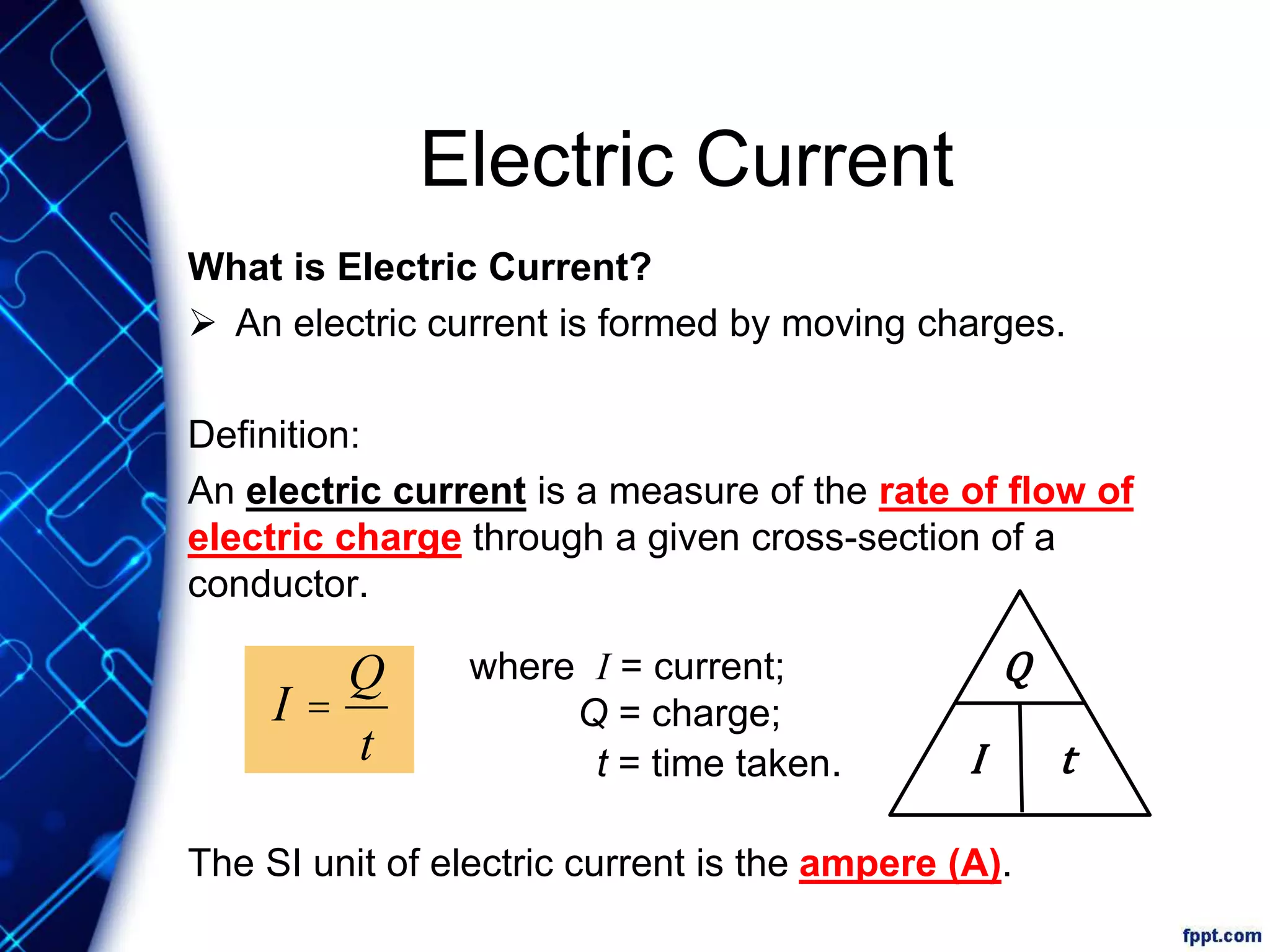

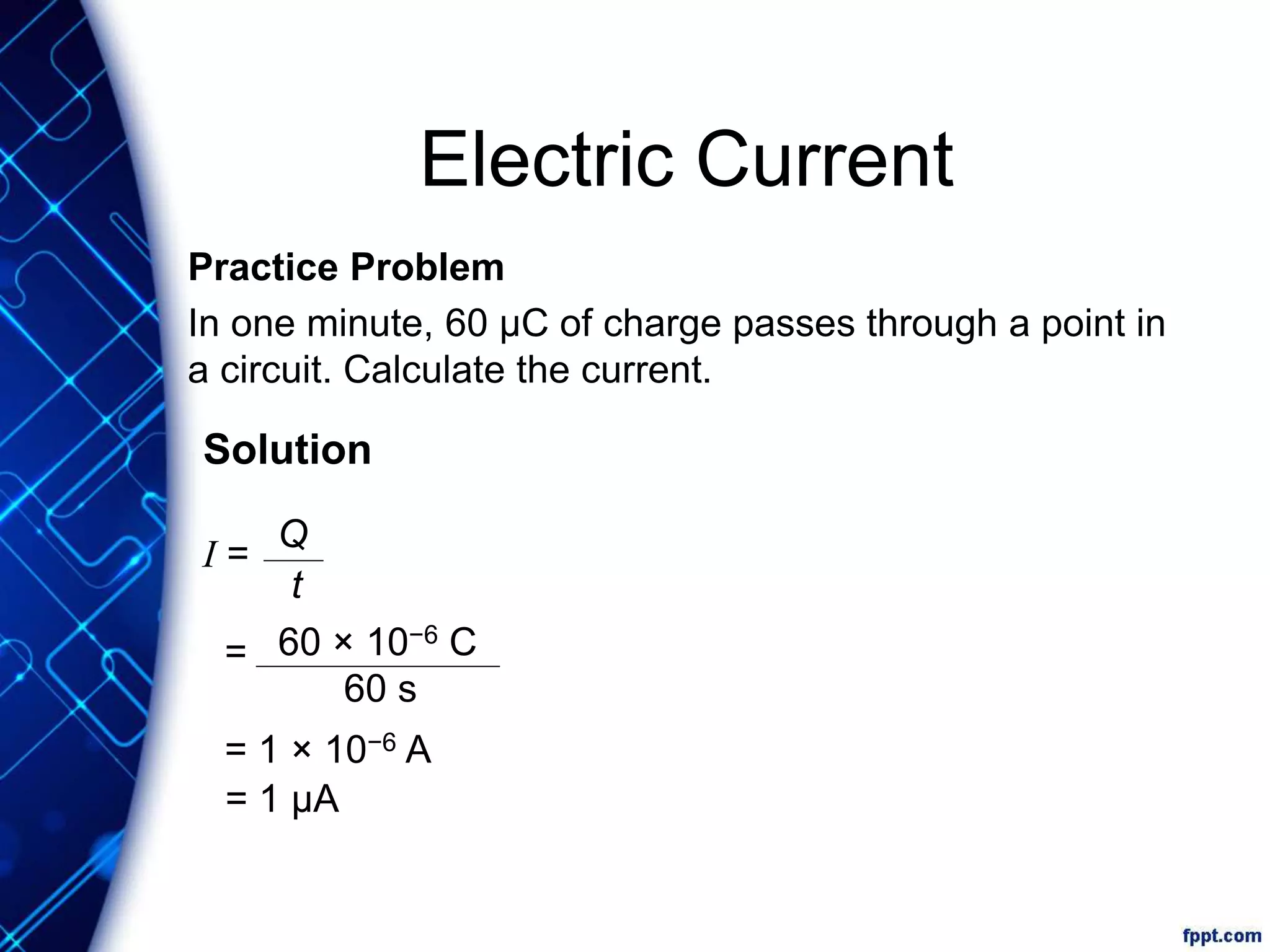

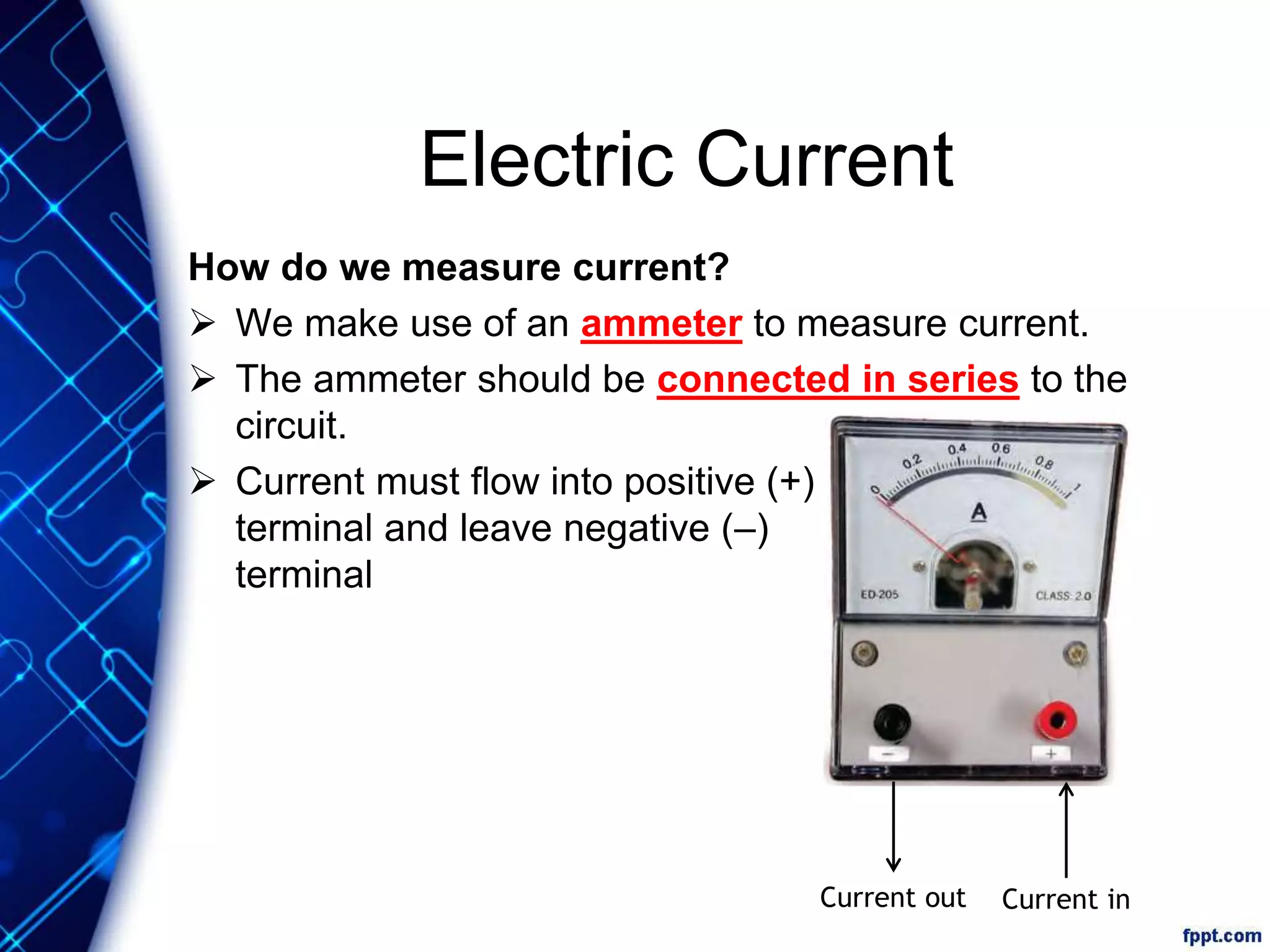

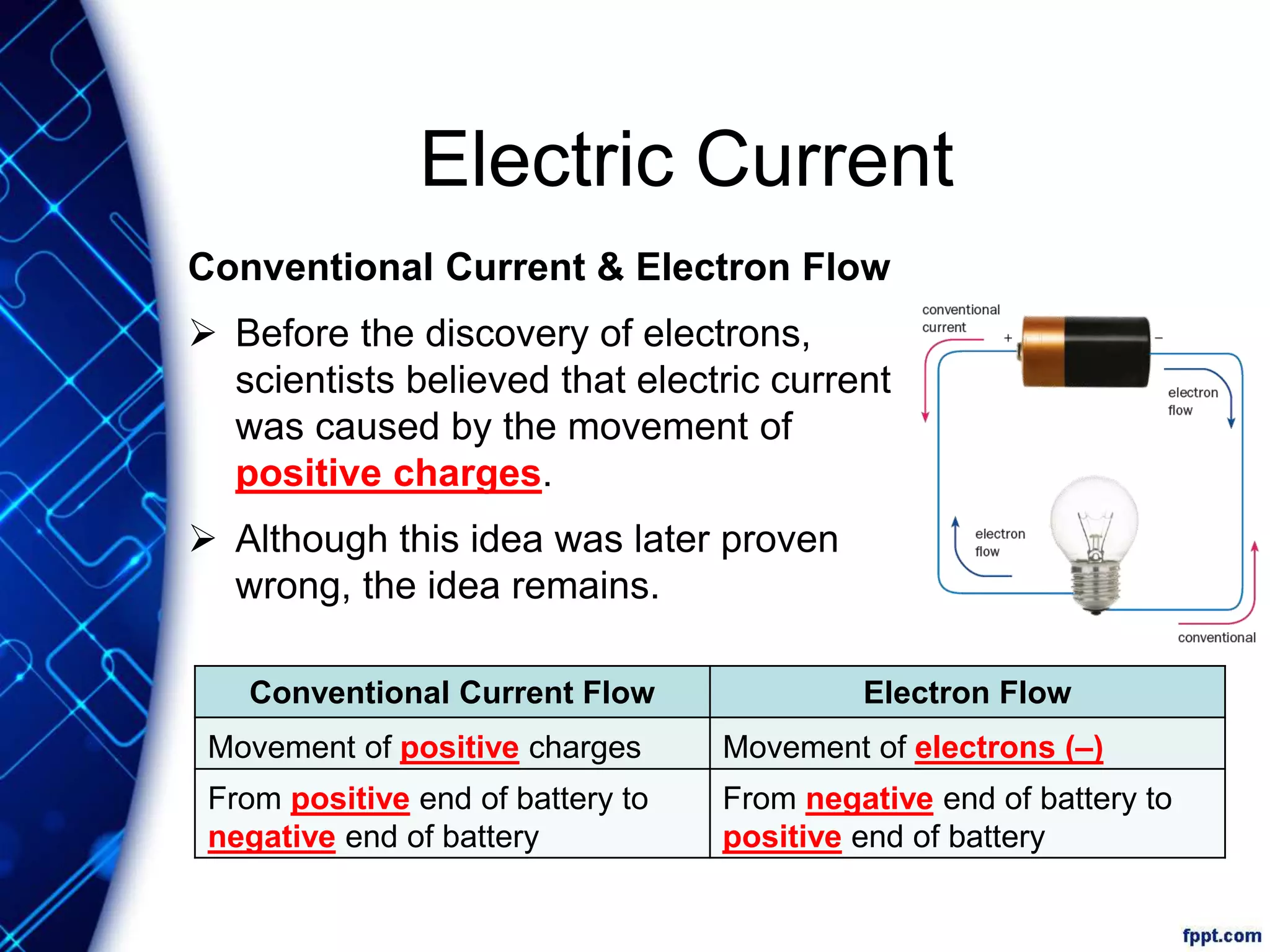

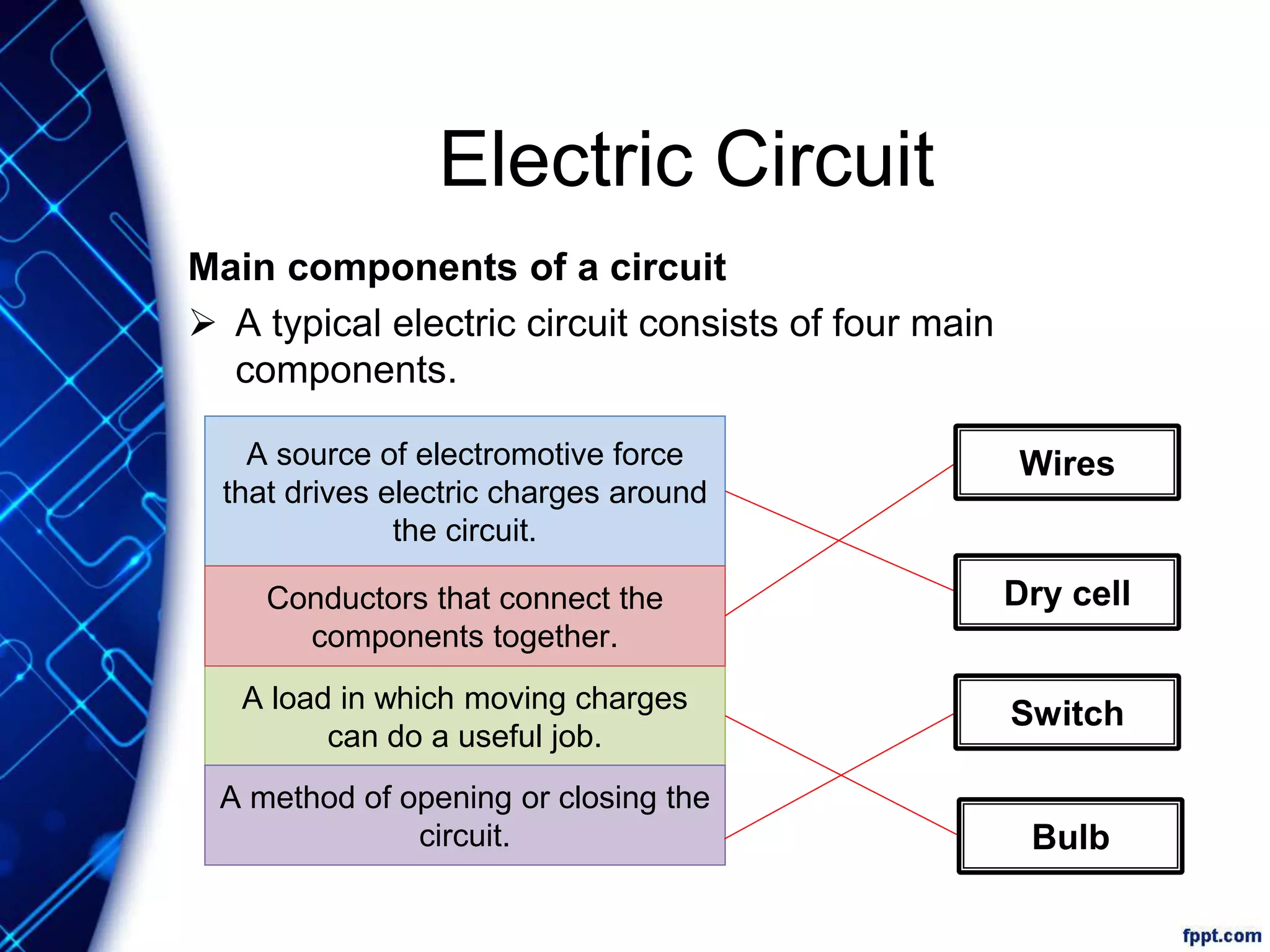

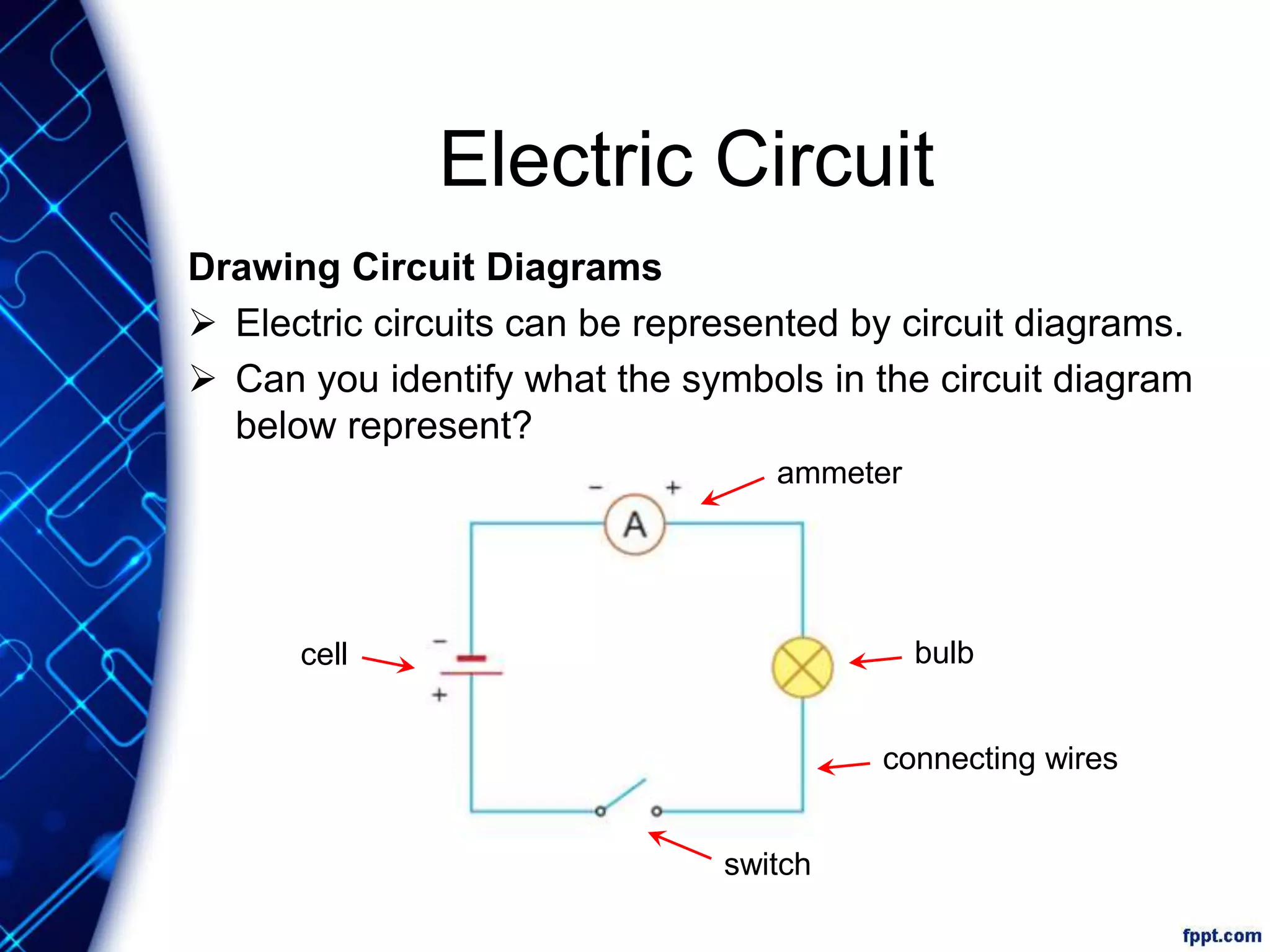

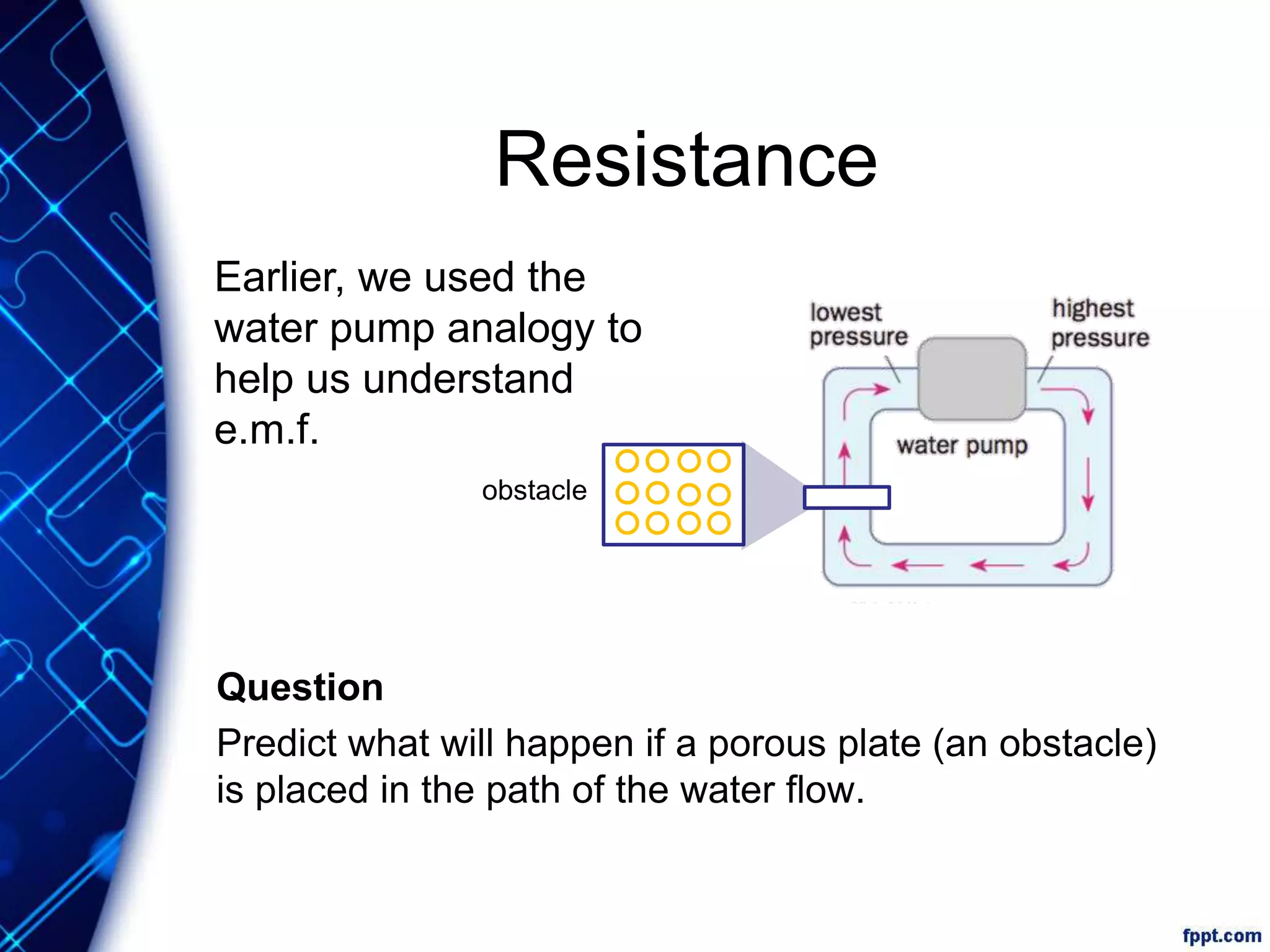

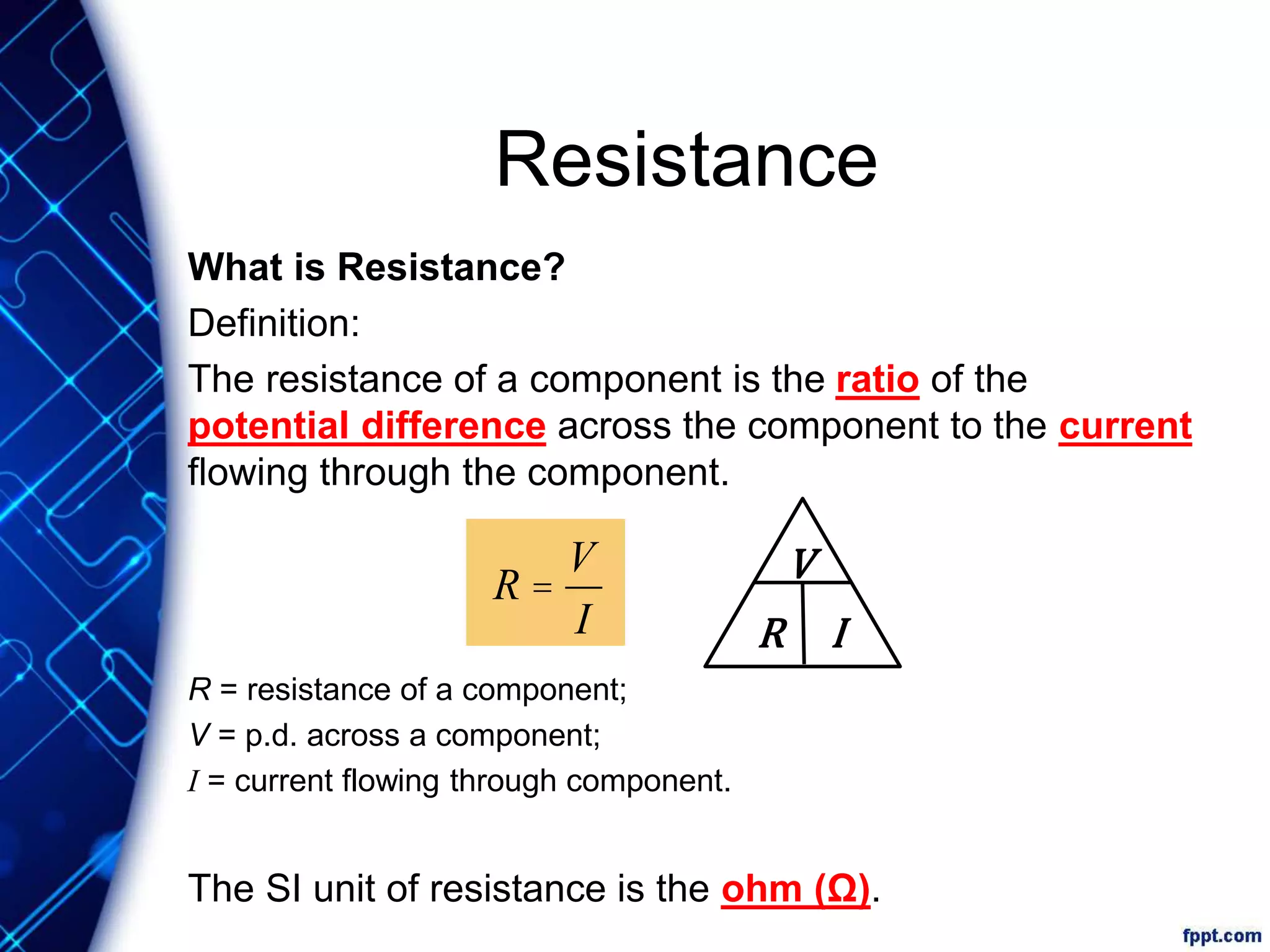

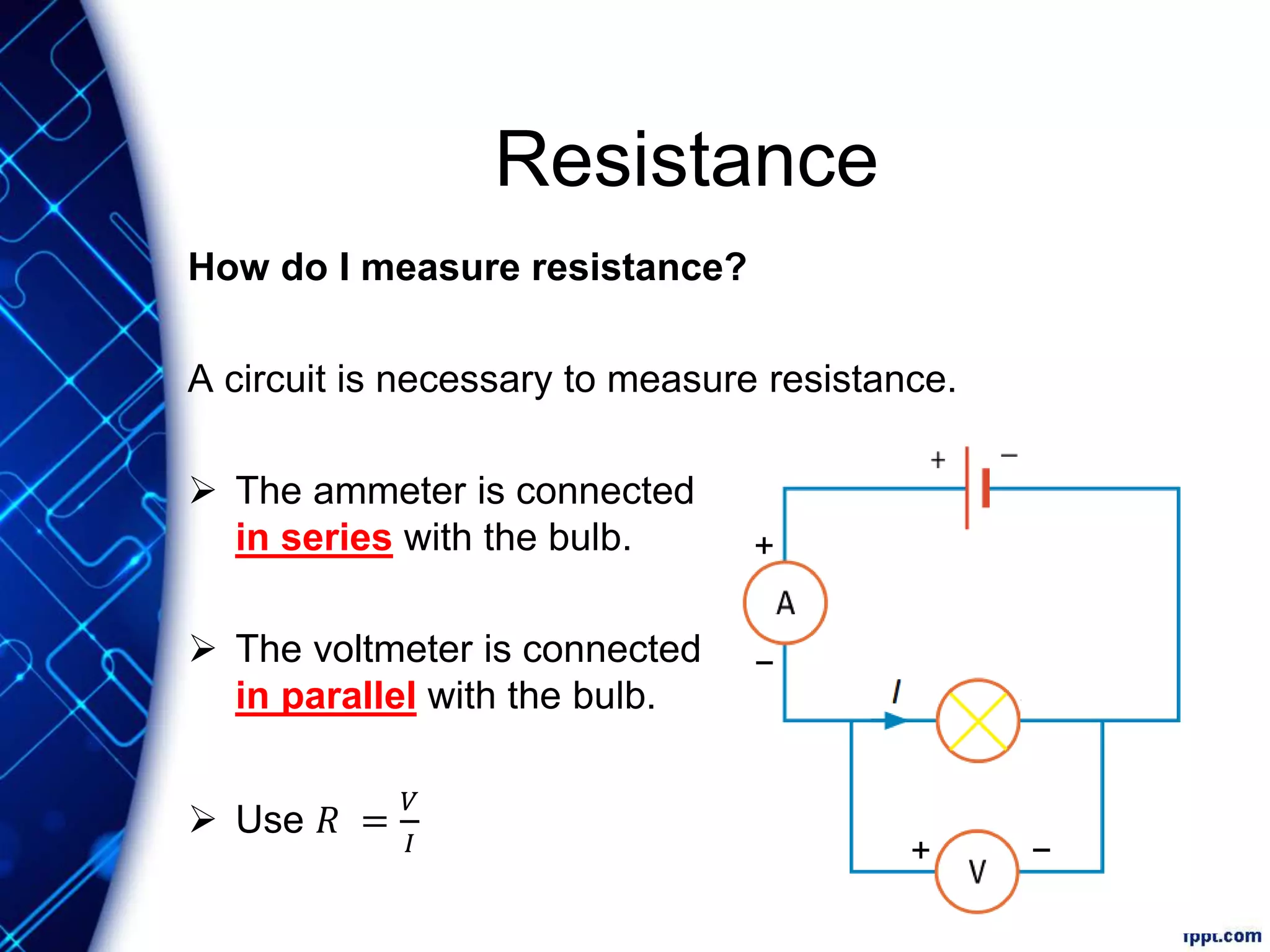

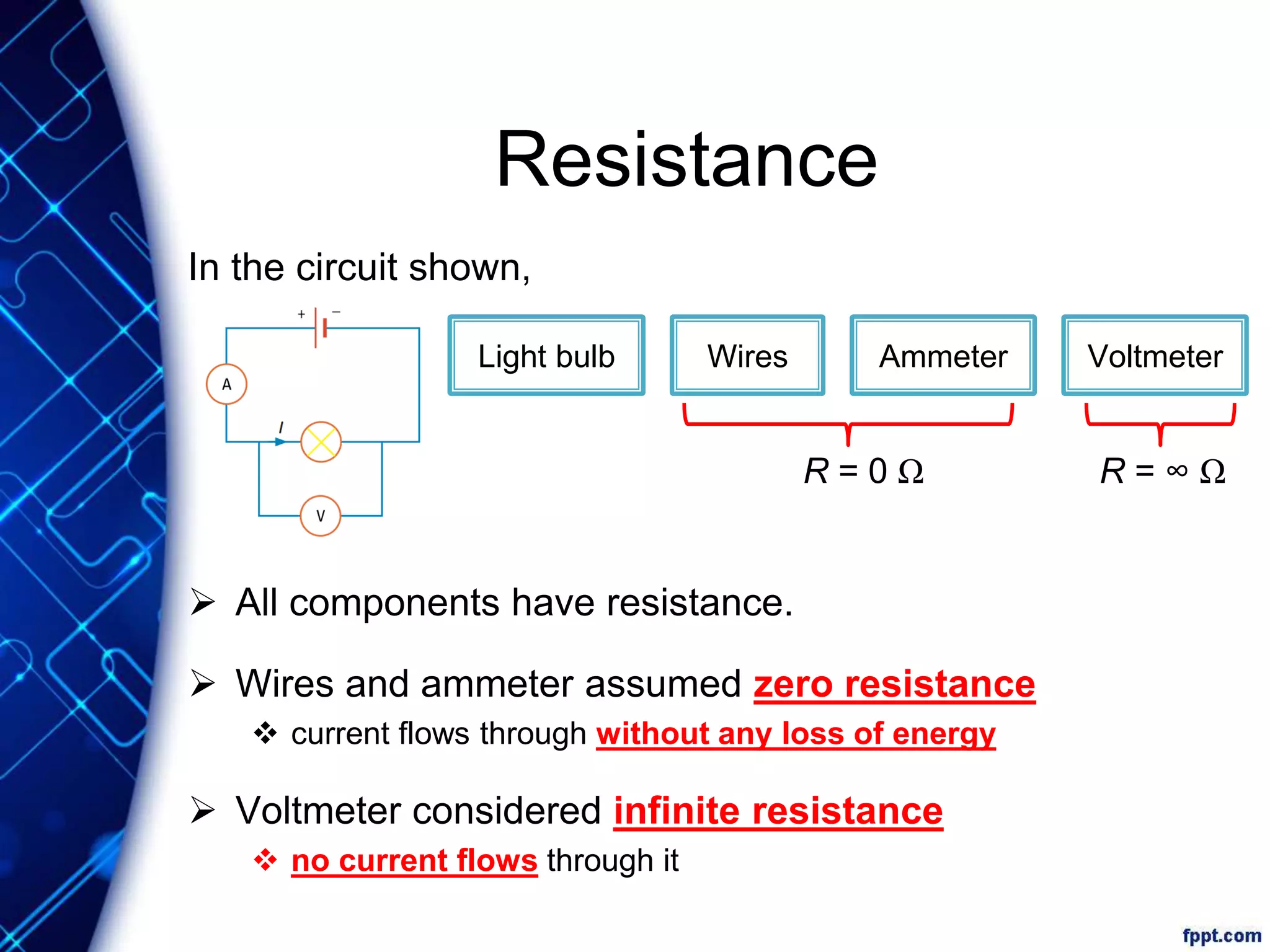

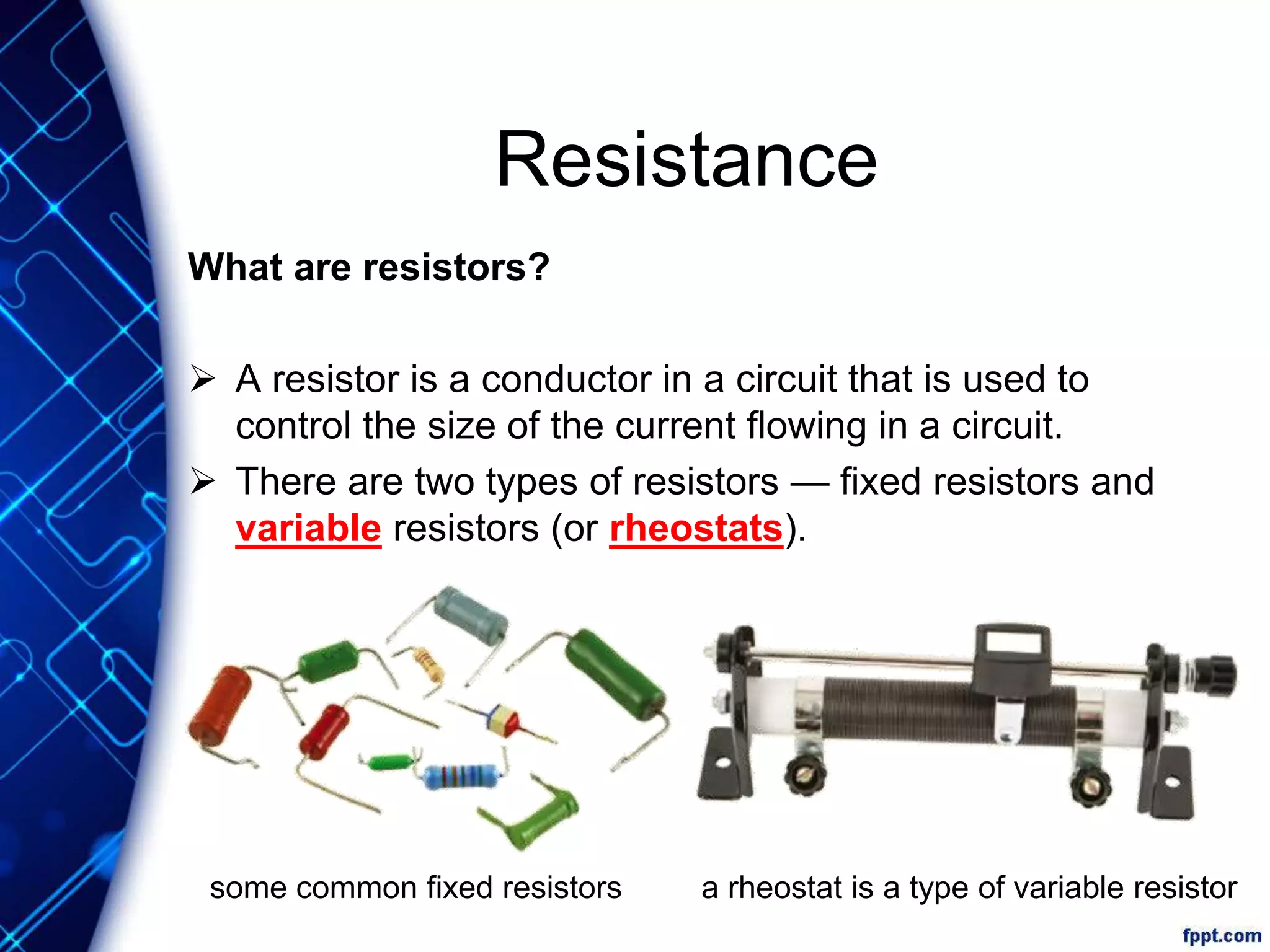

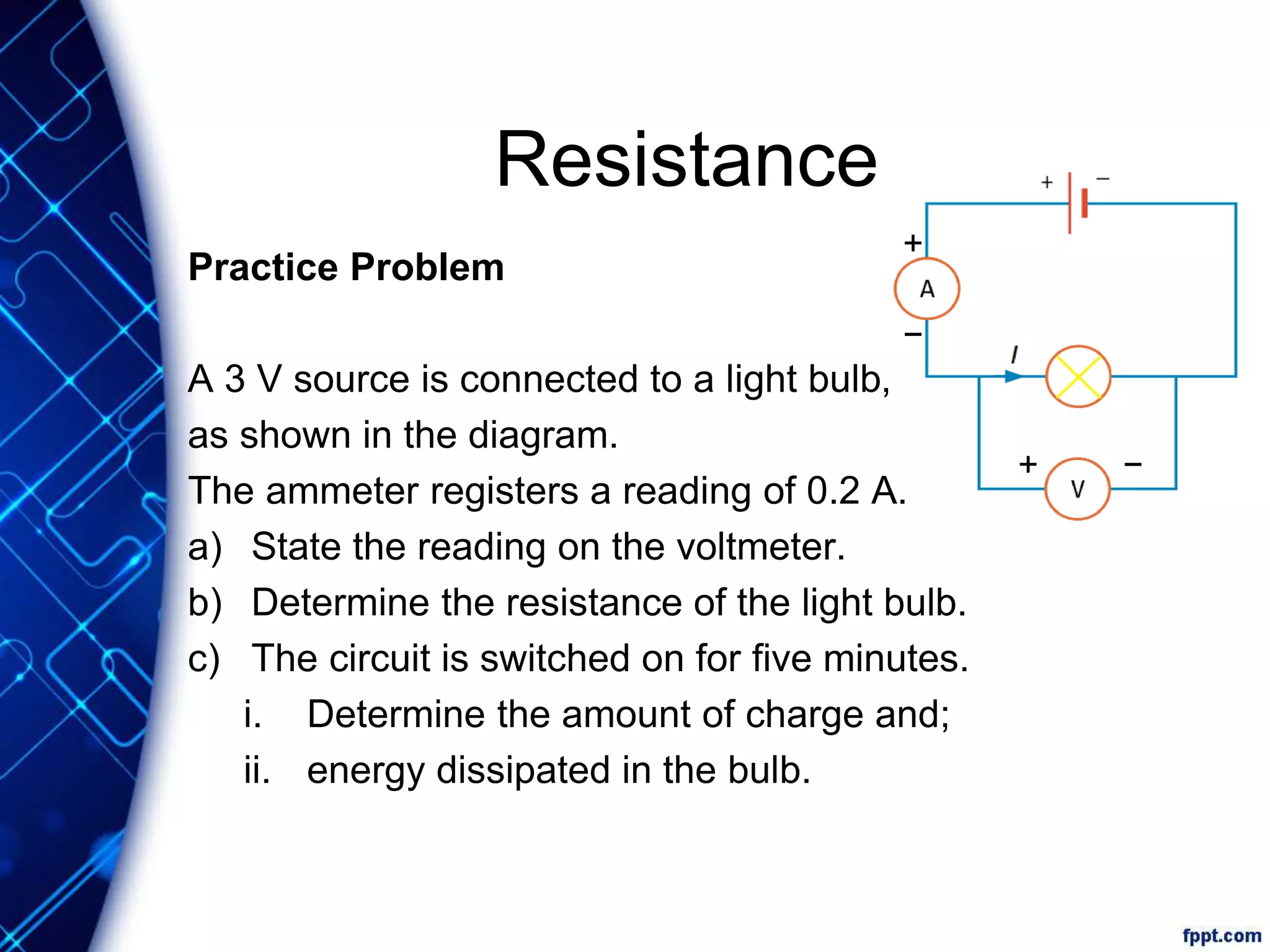

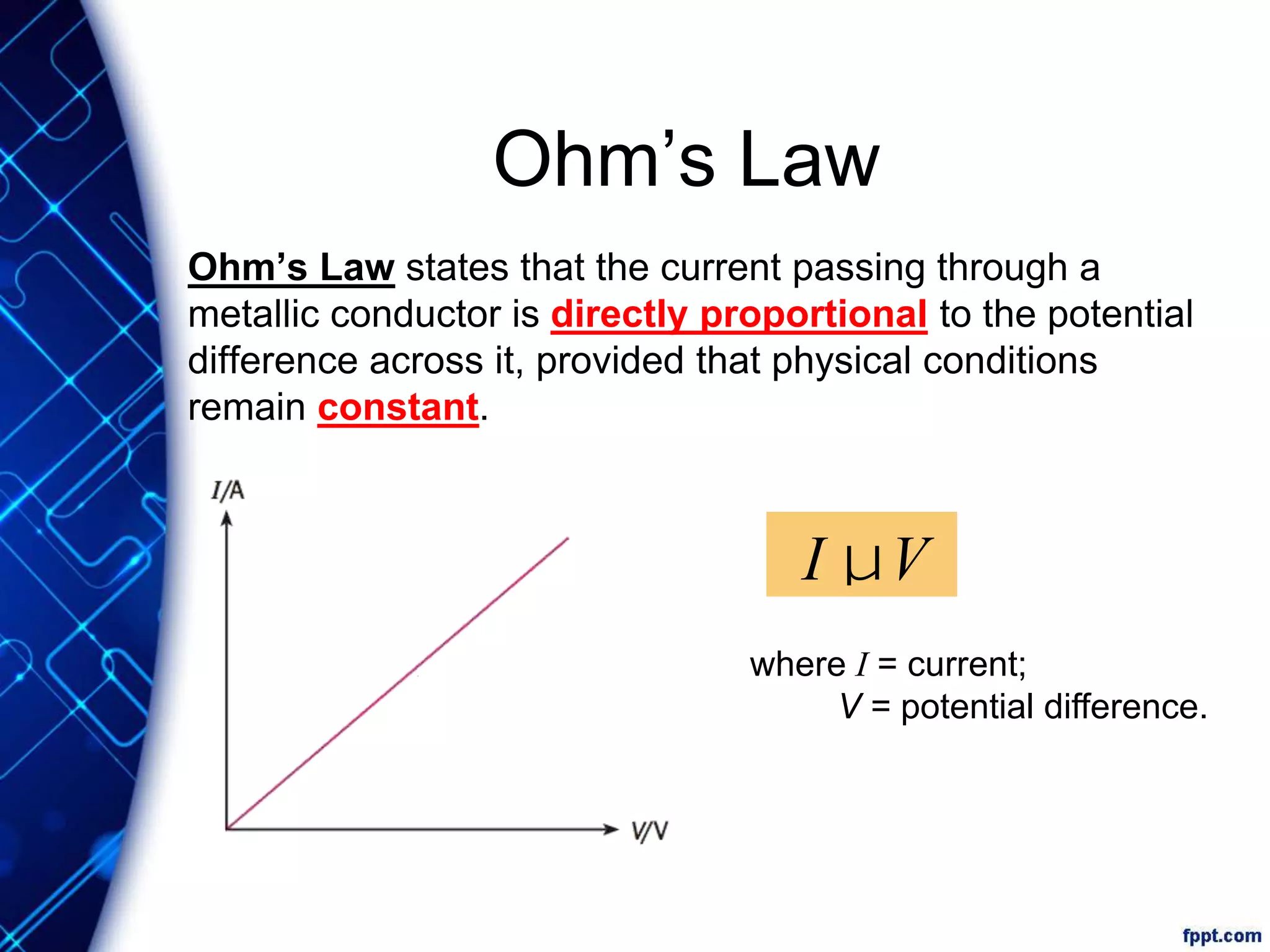

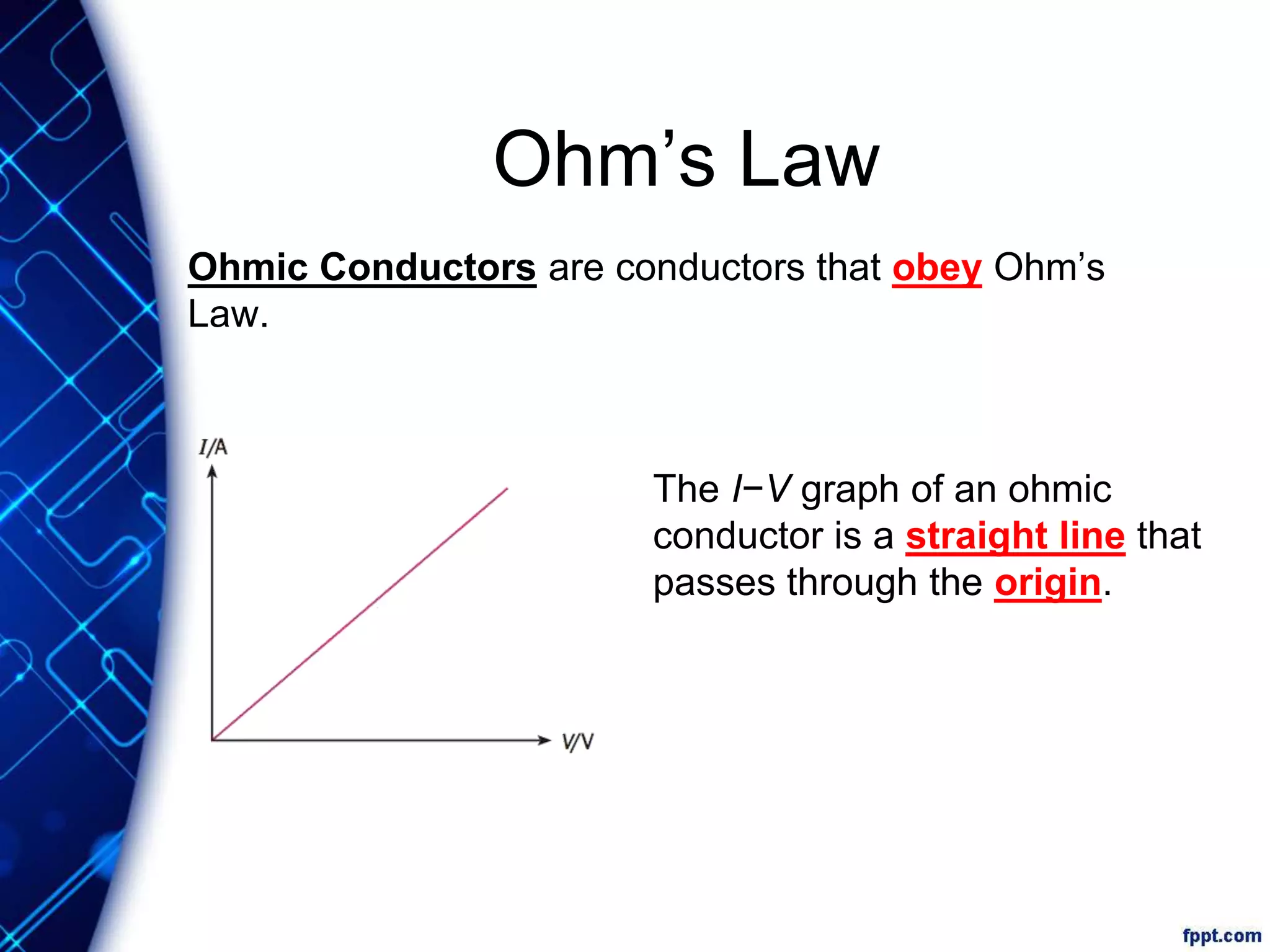

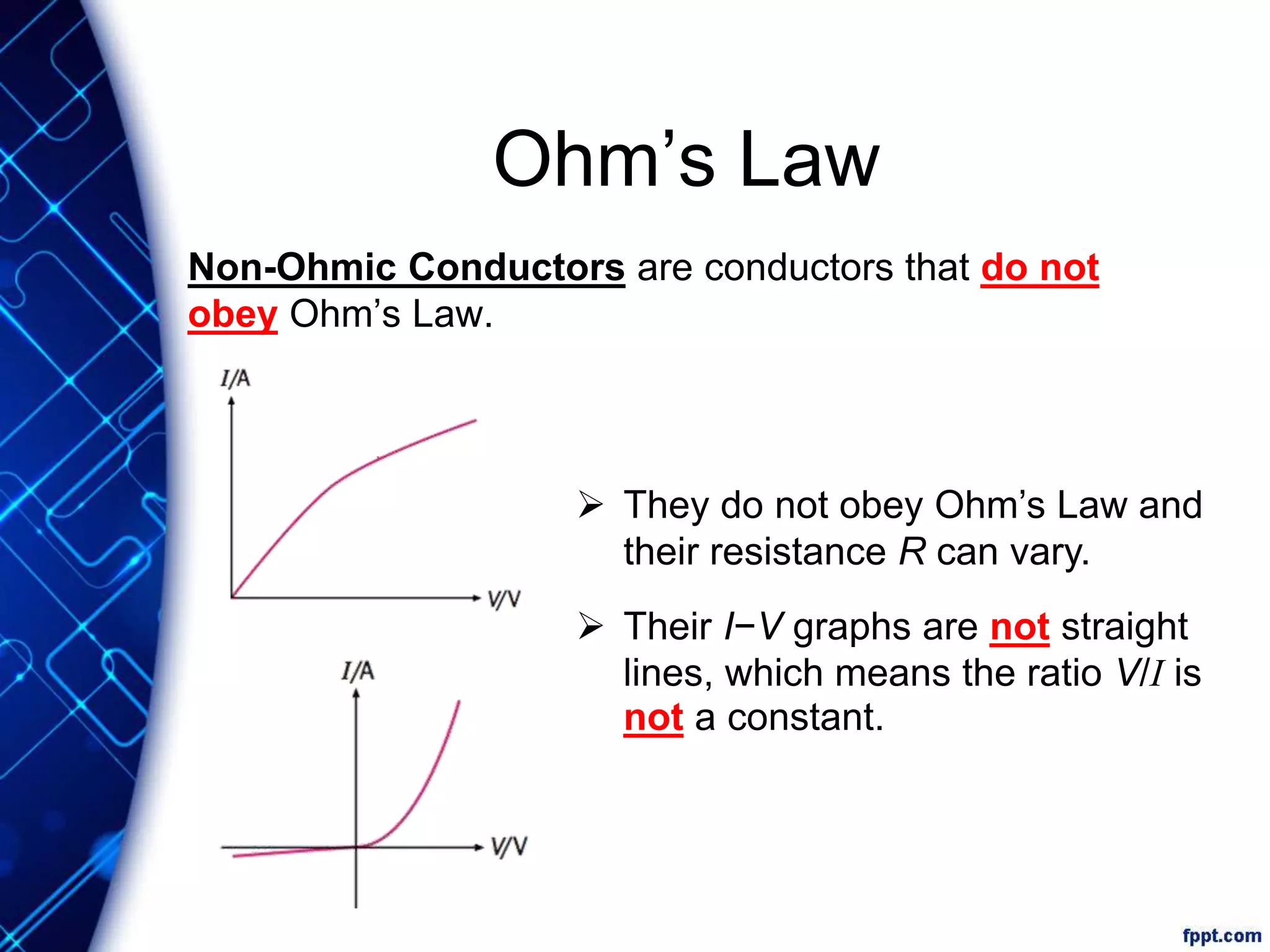

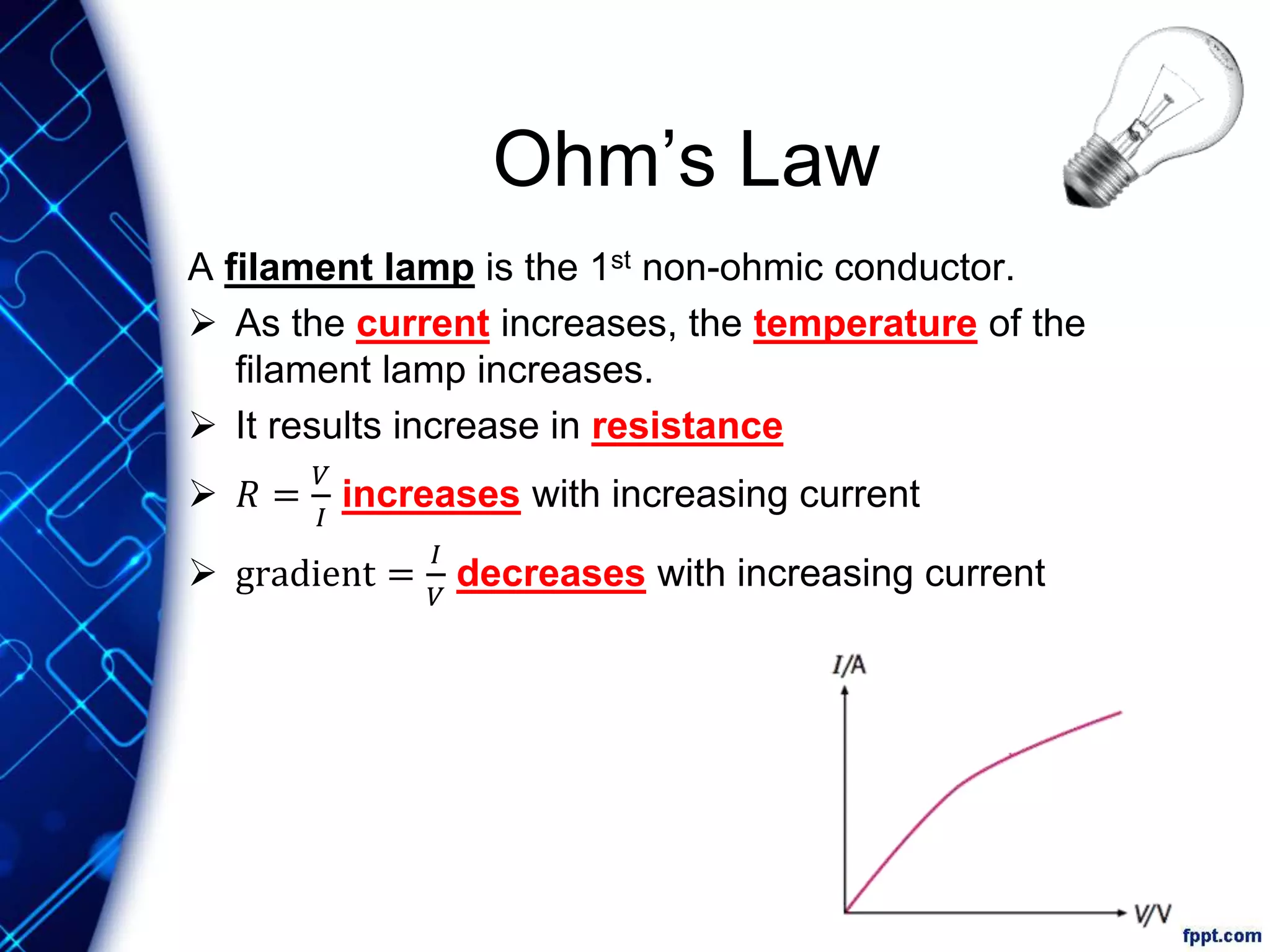

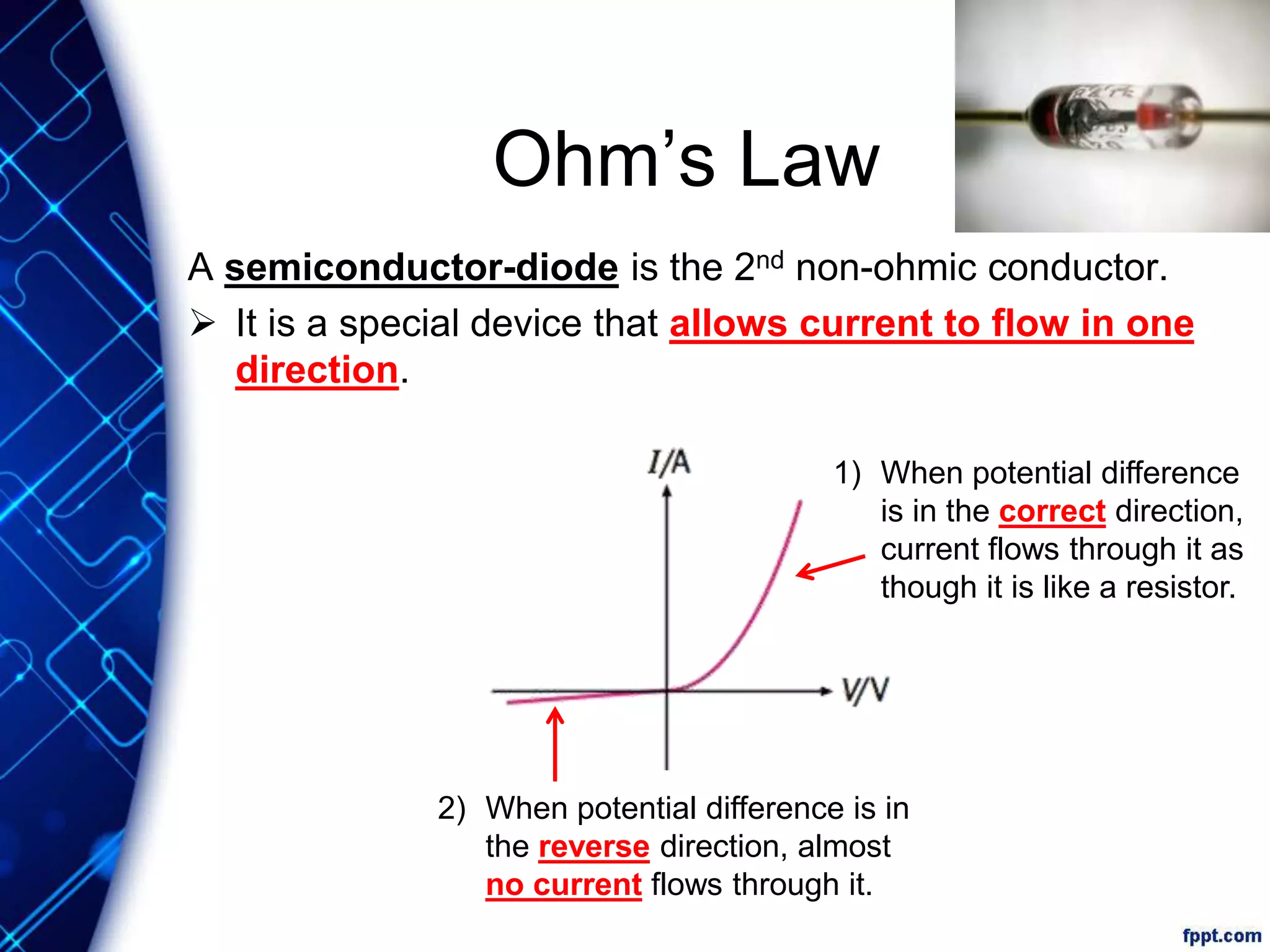

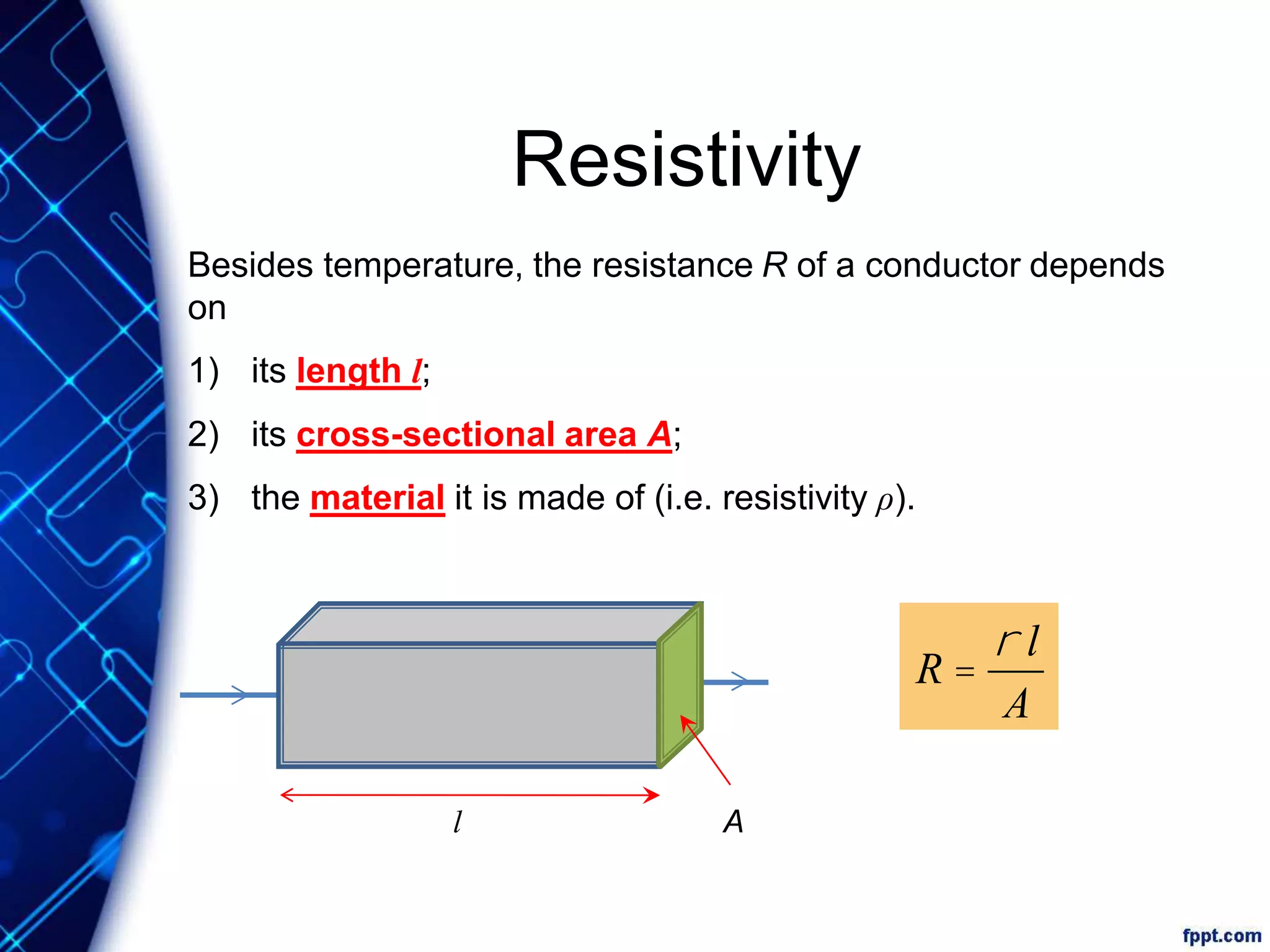

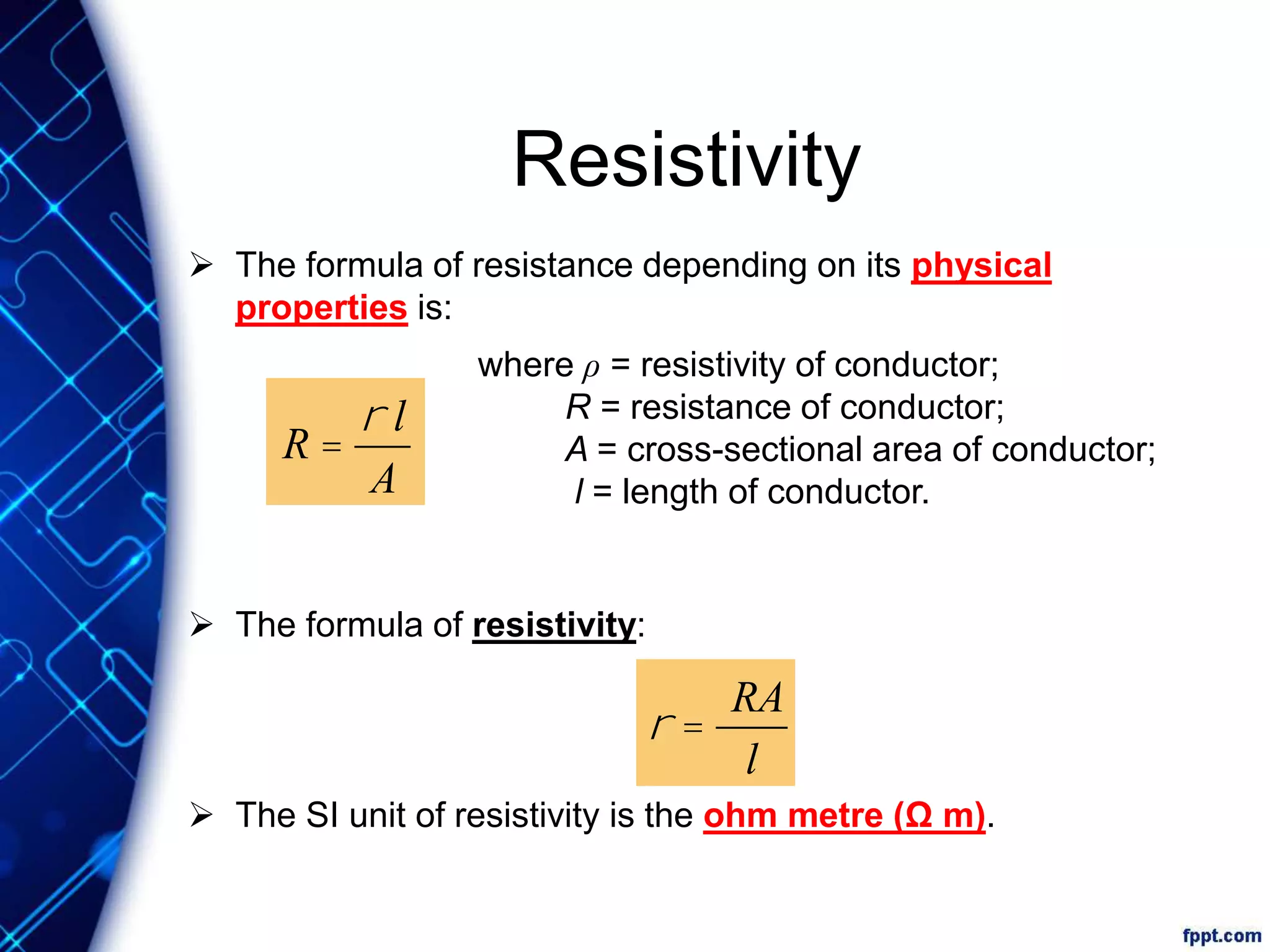

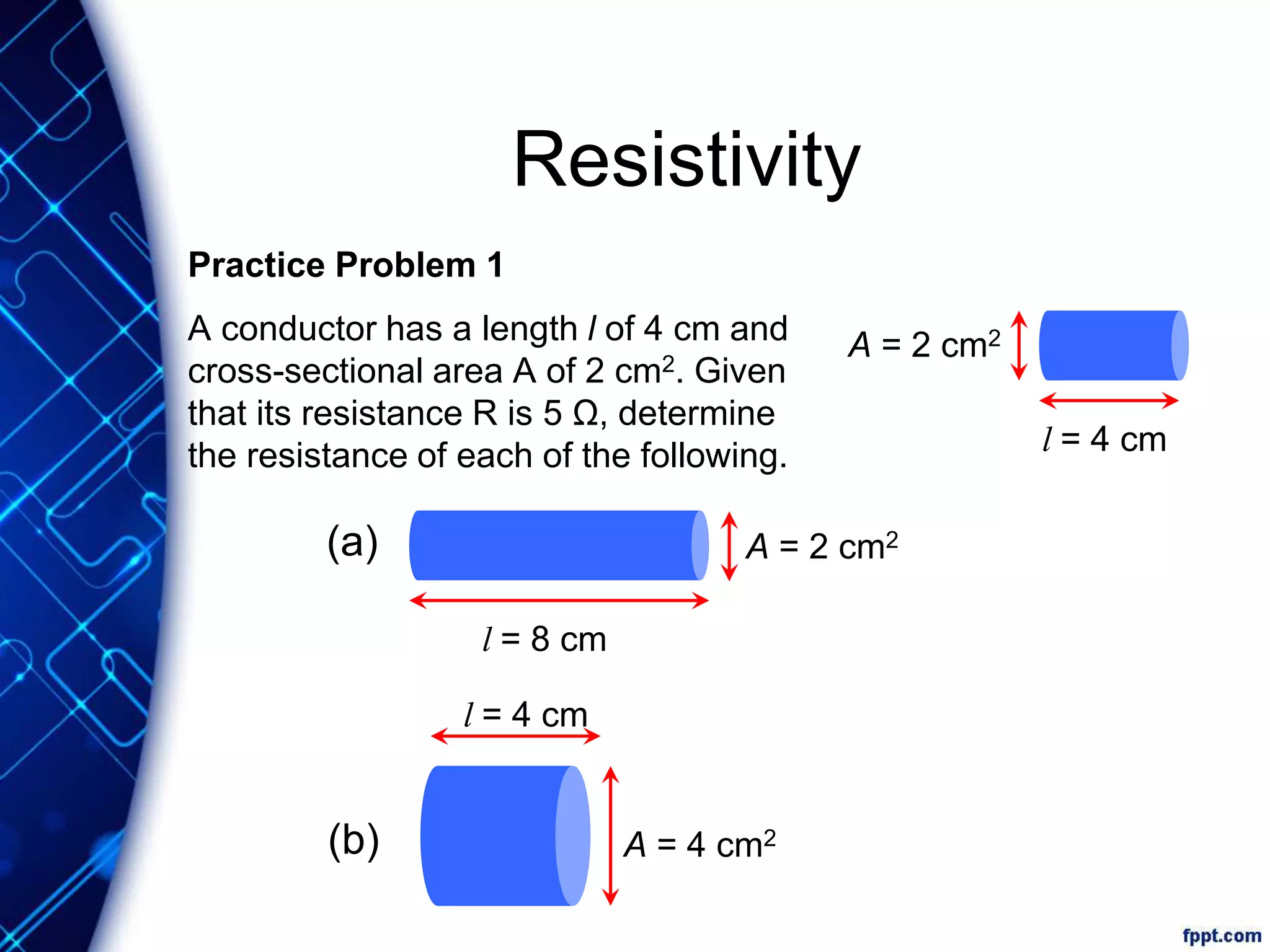

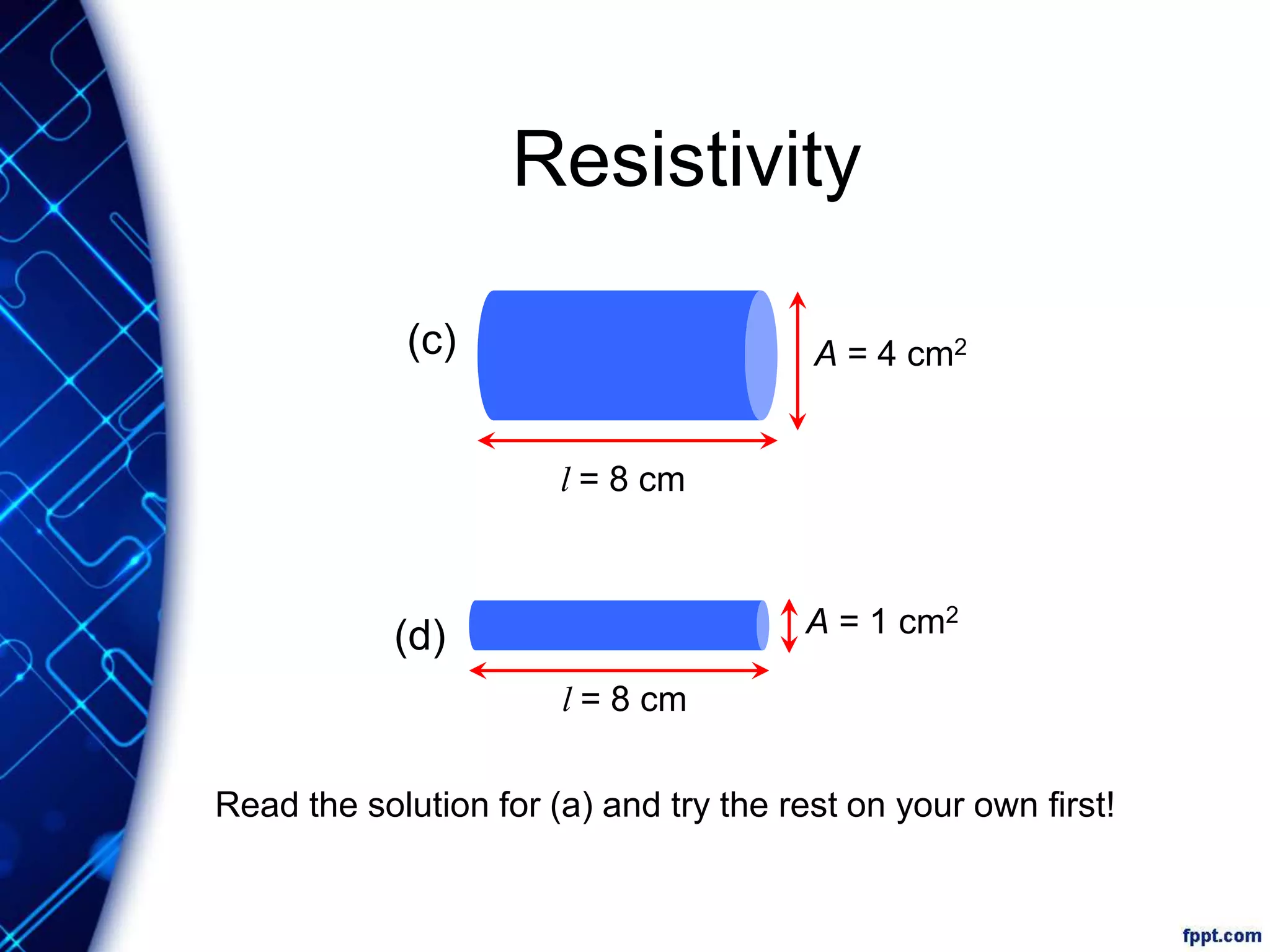

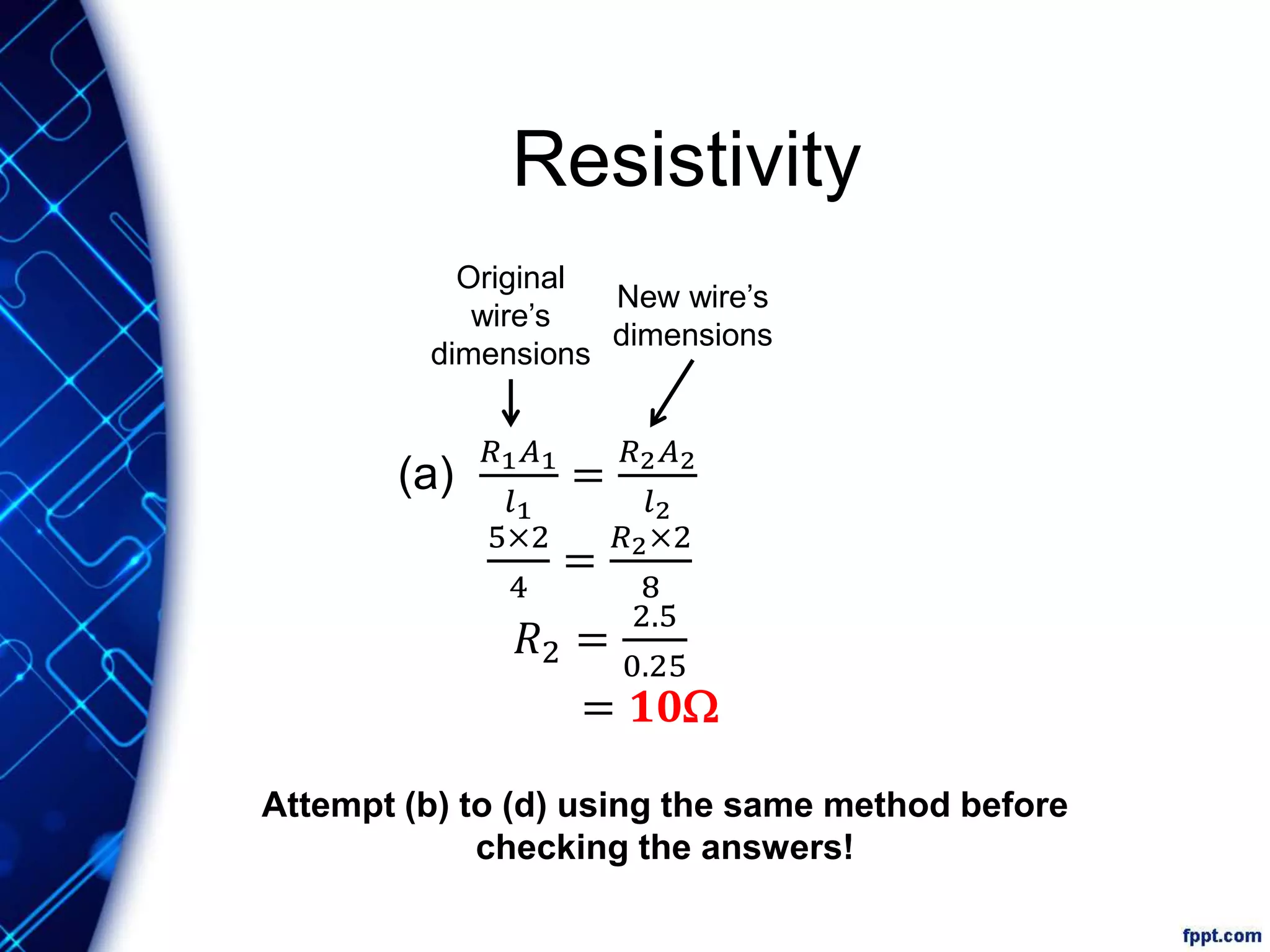

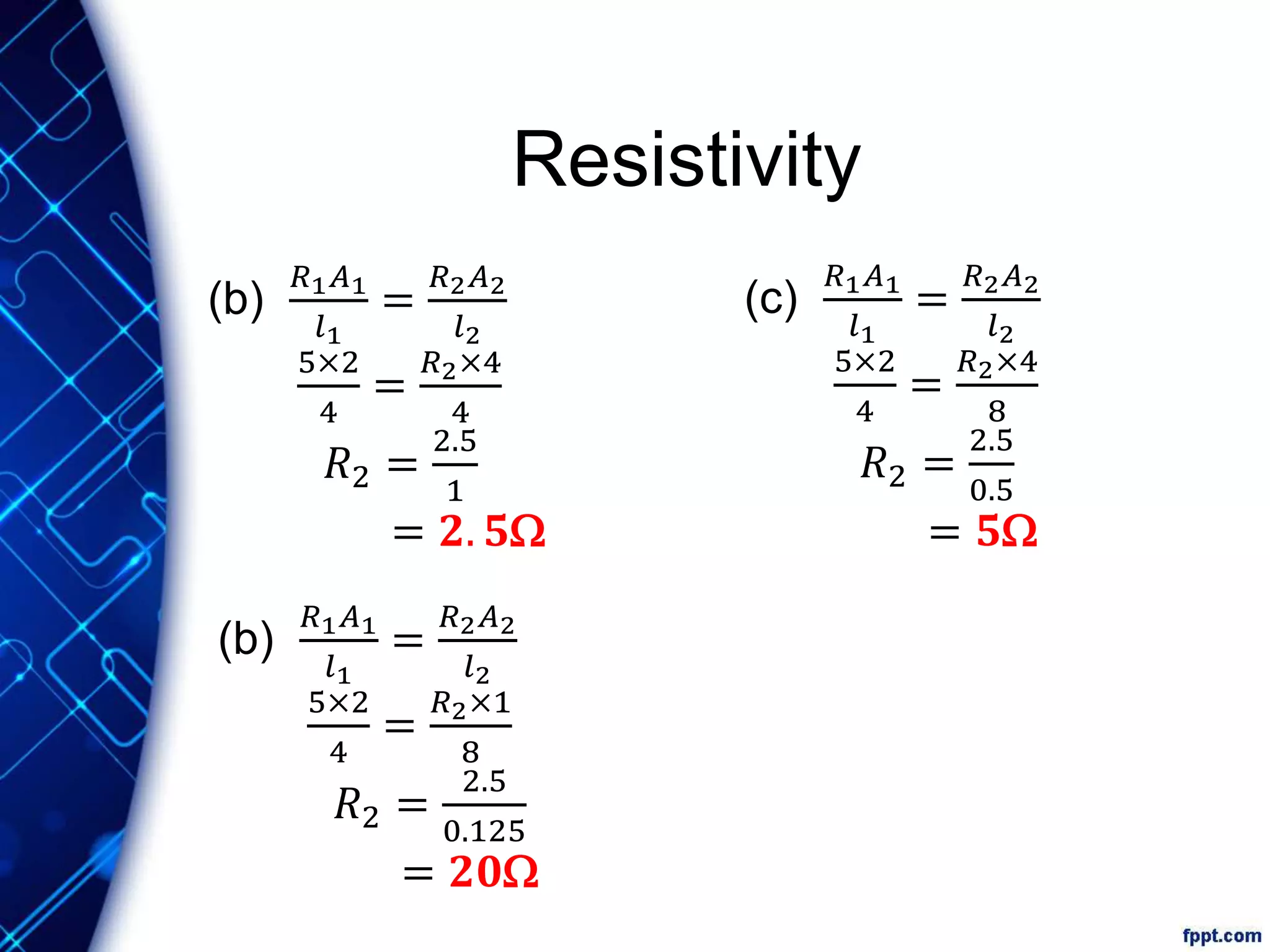

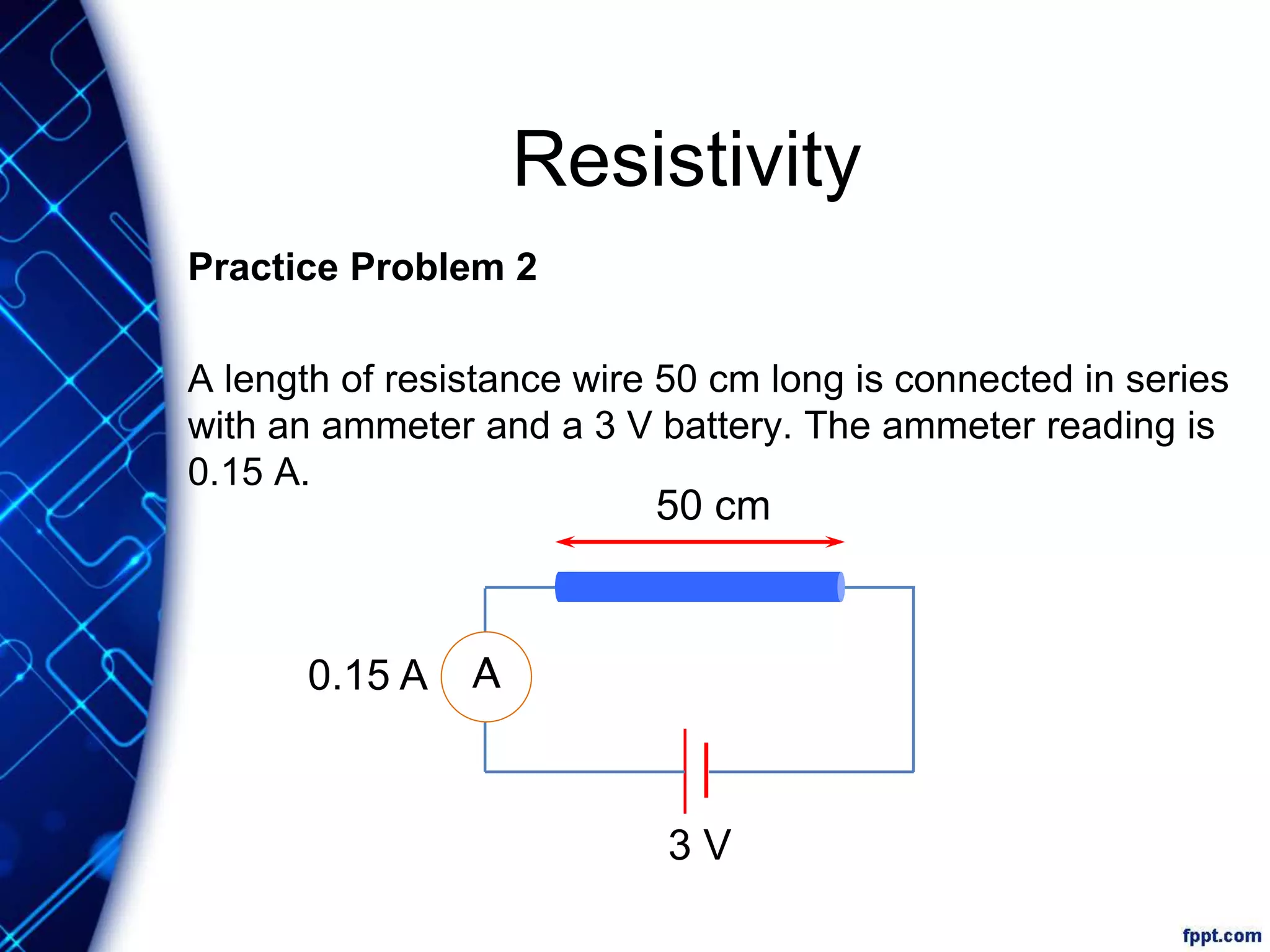

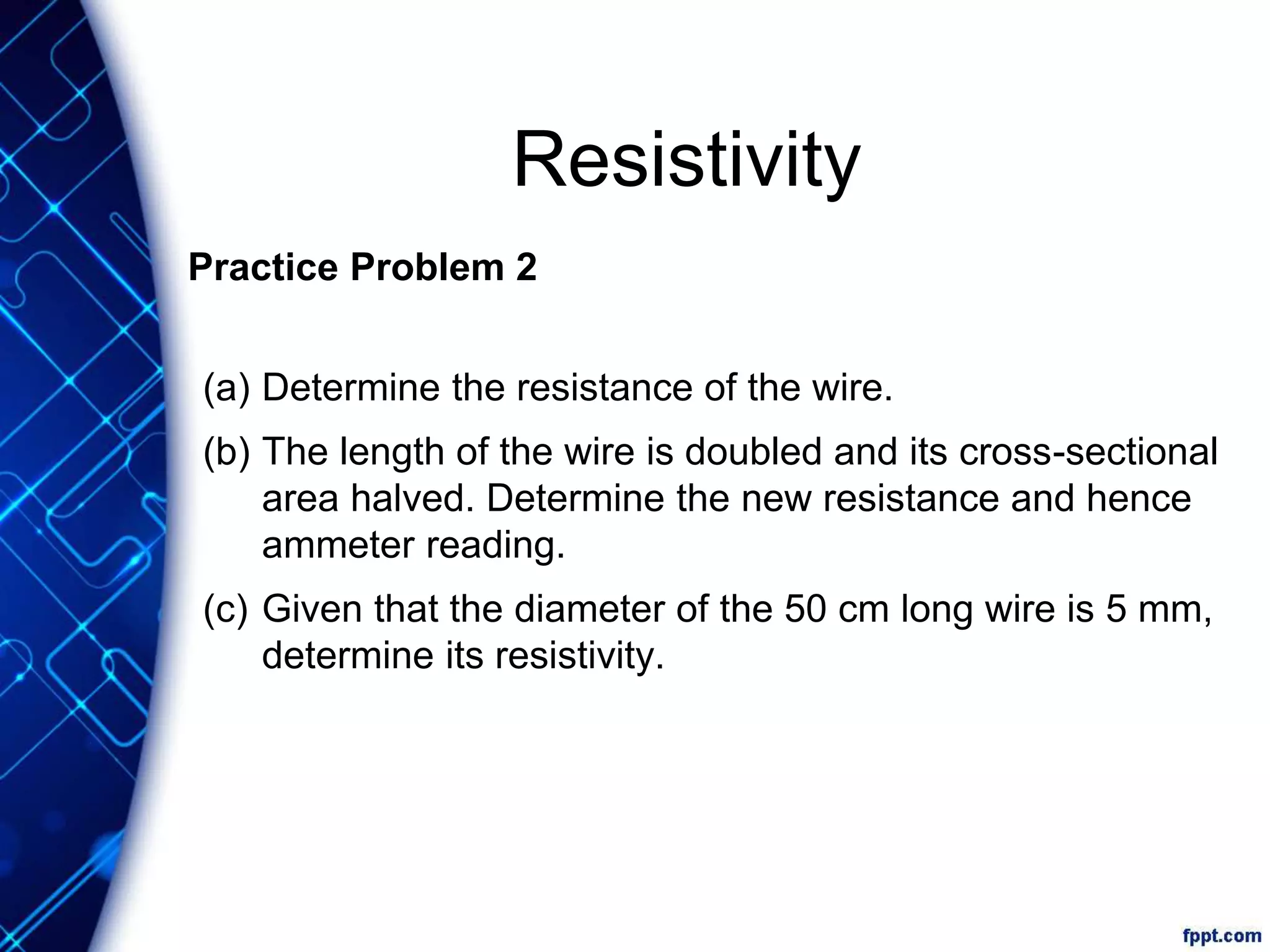

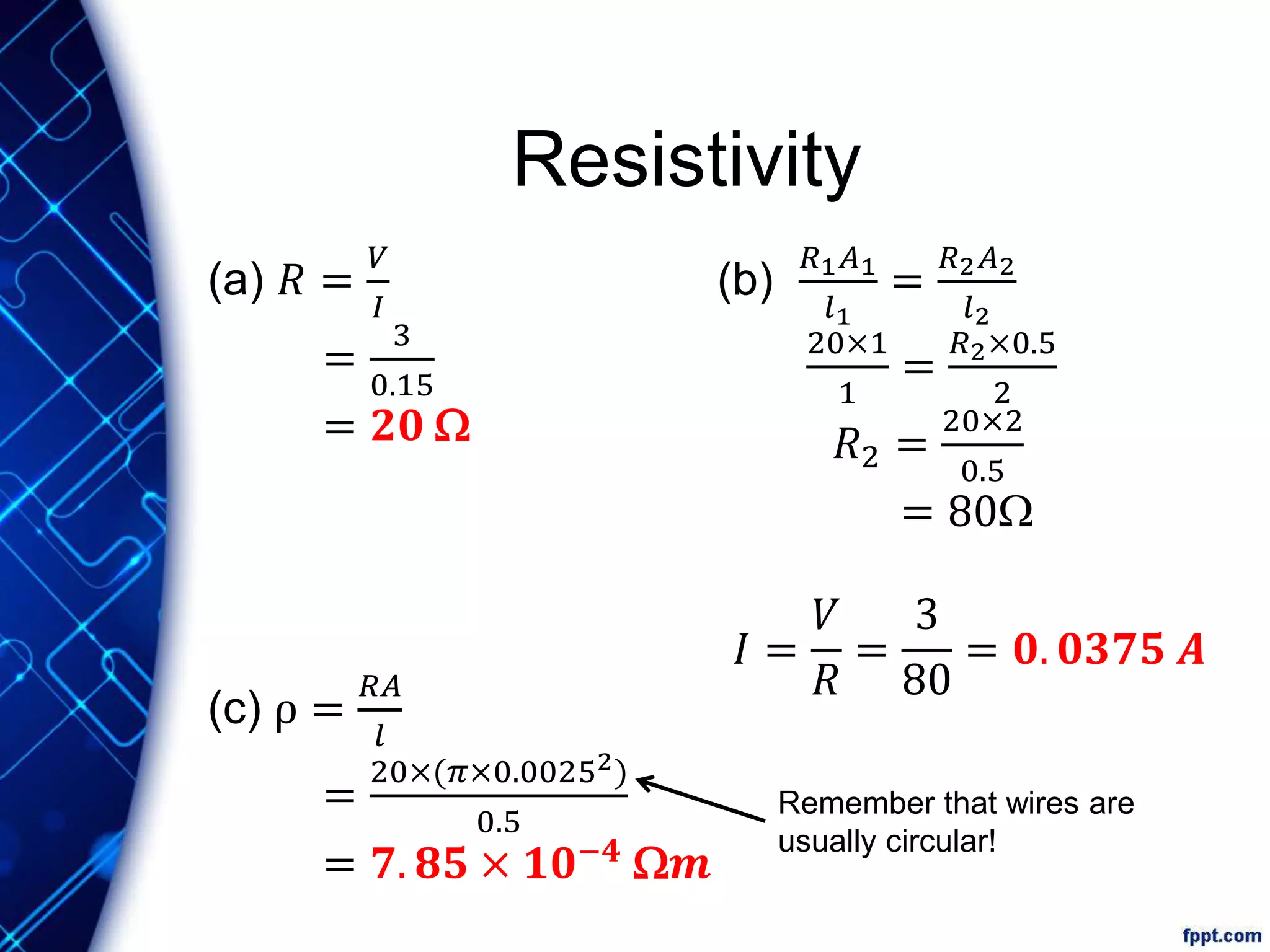

Electric current is the flow of electric charge through a conductor. It is measured in amperes. Current is directly proportional to the rate of flow of charge and inversely proportional to the time taken. Resistance is a measure of how difficult it is for current to flow through a material. It depends on the material's resistivity as well as the conductor's length and cross-sectional area. Ohm's Law states that current is directly proportional to voltage for conductors that obey Ohm's Law. Resistance increases with length or decreases with cross-sectional area for a given material according to the formula for resistivity.