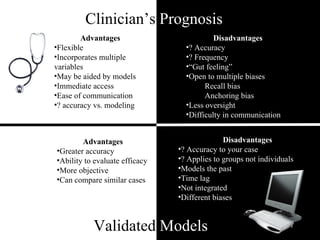

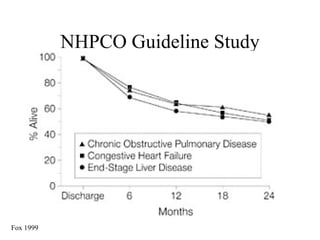

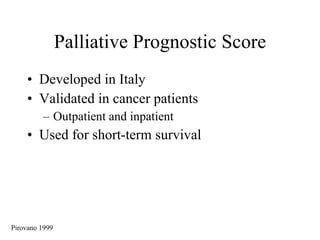

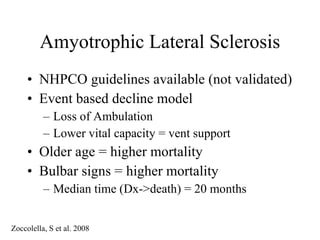

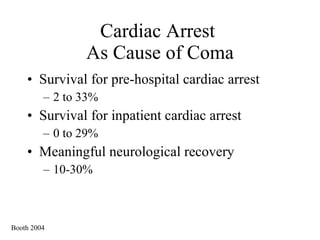

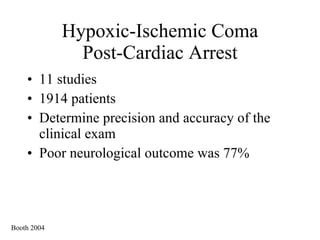

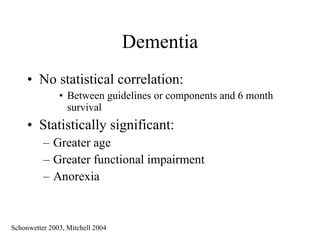

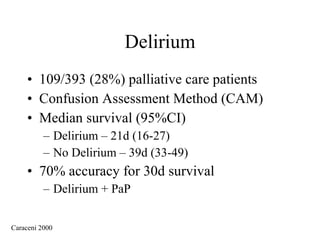

This document discusses the importance and methodology of evidence-based prognostication in medical settings, noting its benefits and limitations. It outlines various prognostic tools and models, emphasizes the necessity for accurate and compassionate communication of prognosis to patients, and reviews specific prognostic factors across different diseases. The conclusion reinforces that effective prognostication is a skill that can be improved with appropriate tools and practices.

![Contributors Michelle Affield, MD Fellow, Univ of Kansas – Hem/Onc FellowKansas City Hospice & Palliative Care, Kansas City, MO Michael Salacz, MD Saint Luke’s Hospital, Kansas City, MO Assistant Professor, University of Missouri, Kansas City, MO msalacz@saint-lukes.org Christian Sinclair, MD Assoc Fellowship Director & Assoc. Med. Dir., Kansas City Hospice & Palliative Care, KC, MO Medical Director, Palliative Care Team, Providence Medical Center, Kansas City, KS [email_address]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ebmprognosticationpeoria20101-100430075253-phpapp01/85/Evidence-Based-Prognostication-Peoria-2010-1-2-320.jpg)