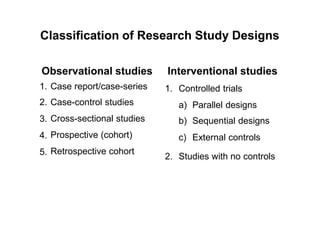

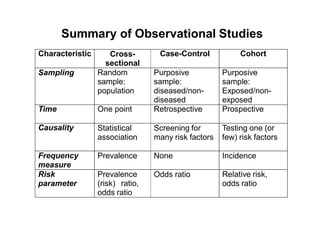

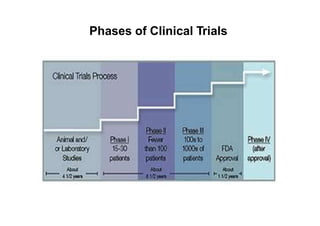

This document provides an overview of different types of clinical study designs, including observational studies and experimental studies. It discusses the key aspects and objectives of different phases of clinical trials, including:

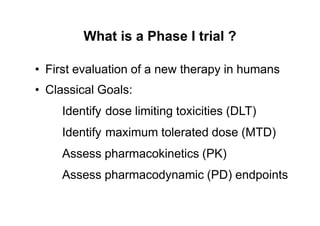

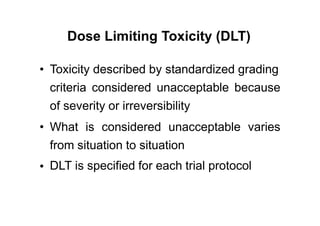

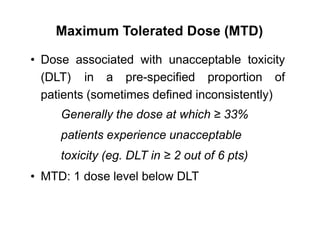

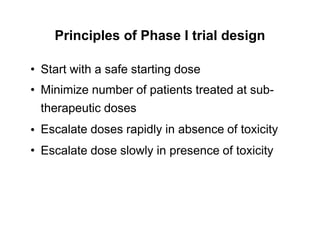

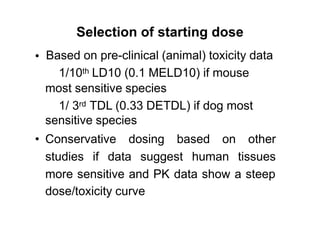

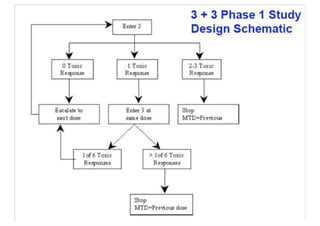

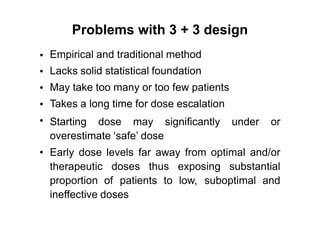

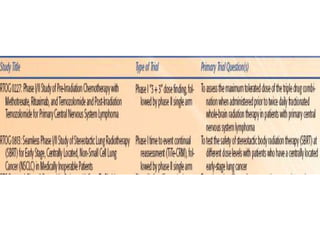

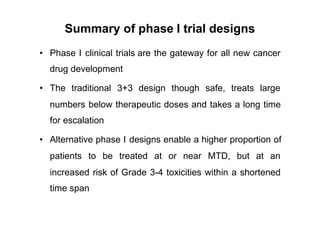

1. Phase I trials which aim to determine safety and maximum tolerated dose of new therapies.

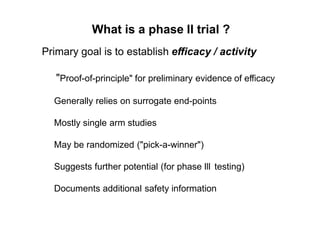

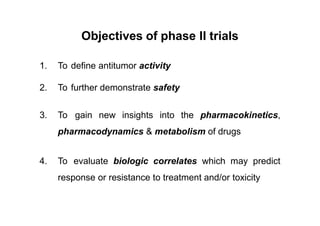

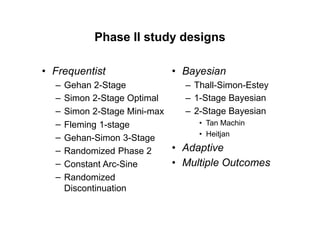

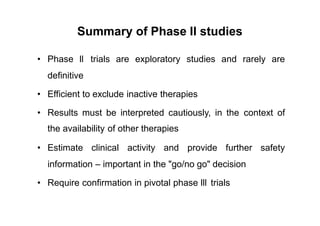

2. Phase II trials which provide preliminary evidence of efficacy through surrogate endpoints and further evaluate safety.

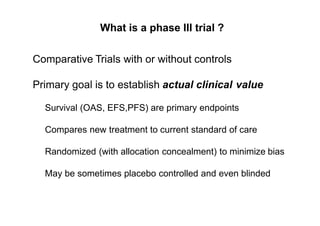

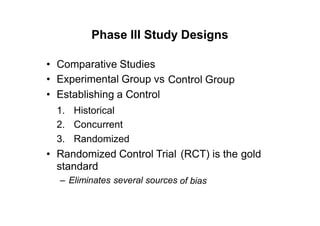

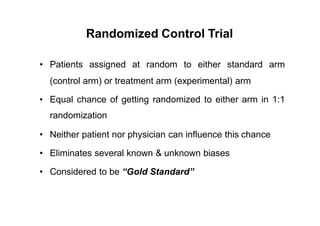

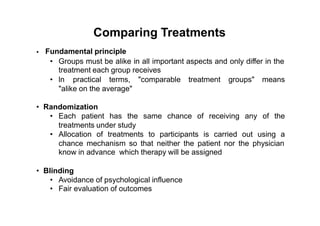

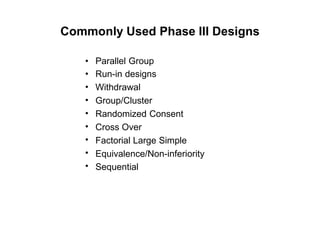

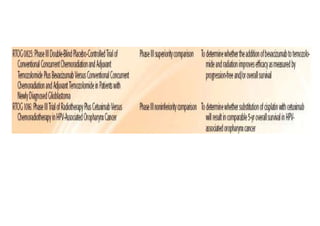

3. Phase III trials which are comparative effectiveness trials that use clinical outcomes like survival to compare new treatments to standard of care through randomized controlled designs.