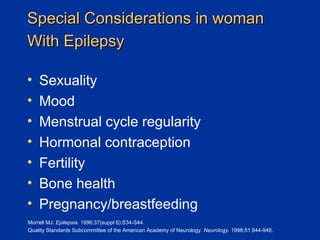

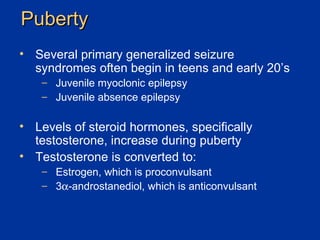

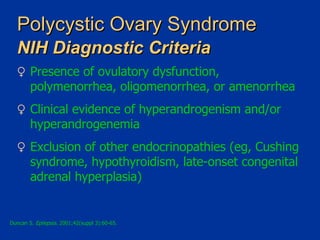

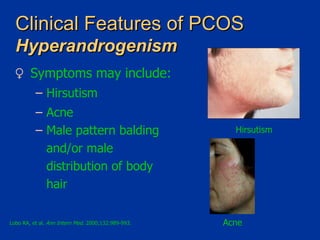

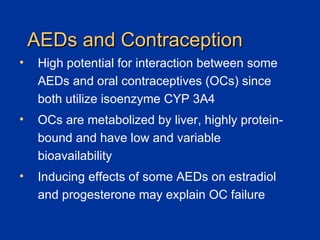

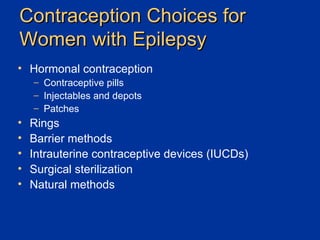

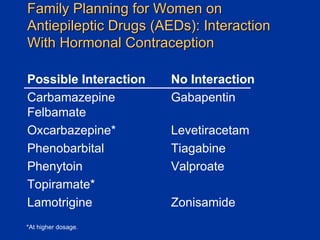

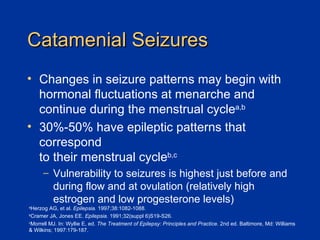

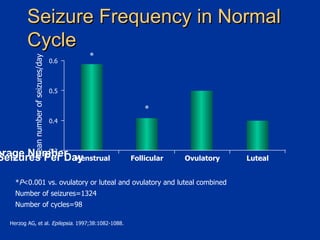

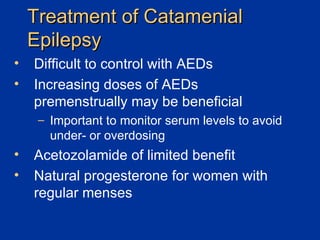

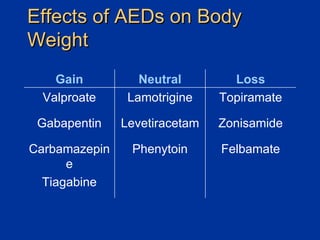

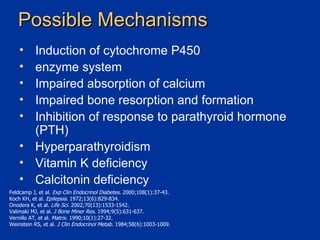

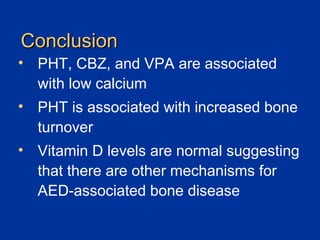

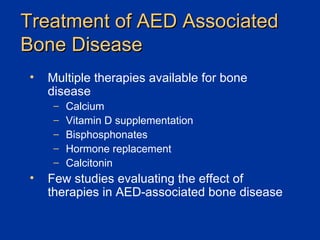

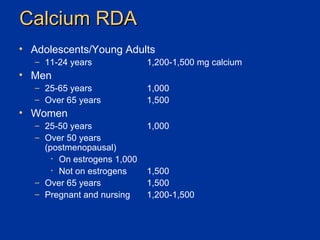

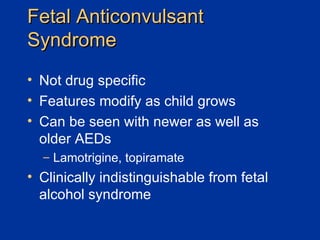

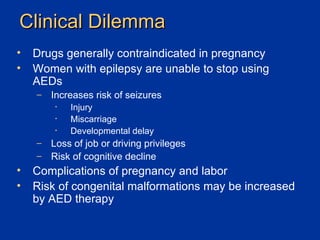

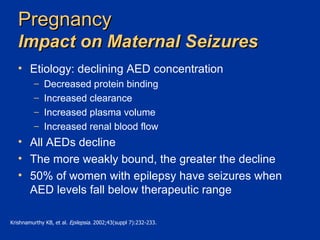

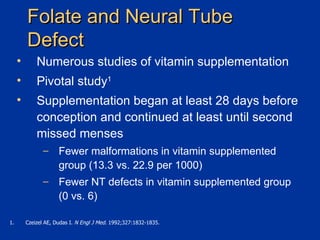

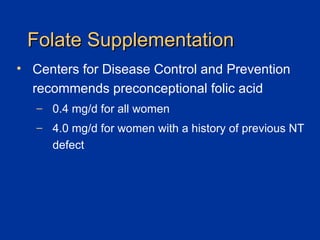

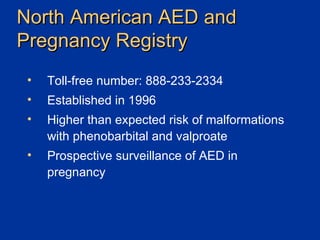

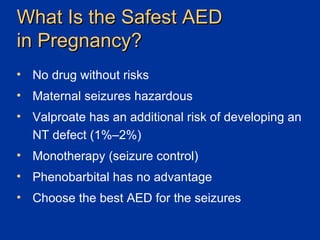

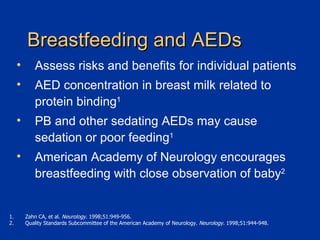

This document summarizes special considerations for women with epilepsy across the reproductive years, including effects on sexuality, mood, menstruation, fertility, bone health, pregnancy, breastfeeding, and menopause. It discusses how epilepsy and antiepileptic drug use can impact these areas through mechanisms like hormonal changes, drug interactions, teratogenic risks, and bone loss. Management involves counseling, supplementation, contraception guidance, monitoring for side effects, and registry participation for pregnant patients.