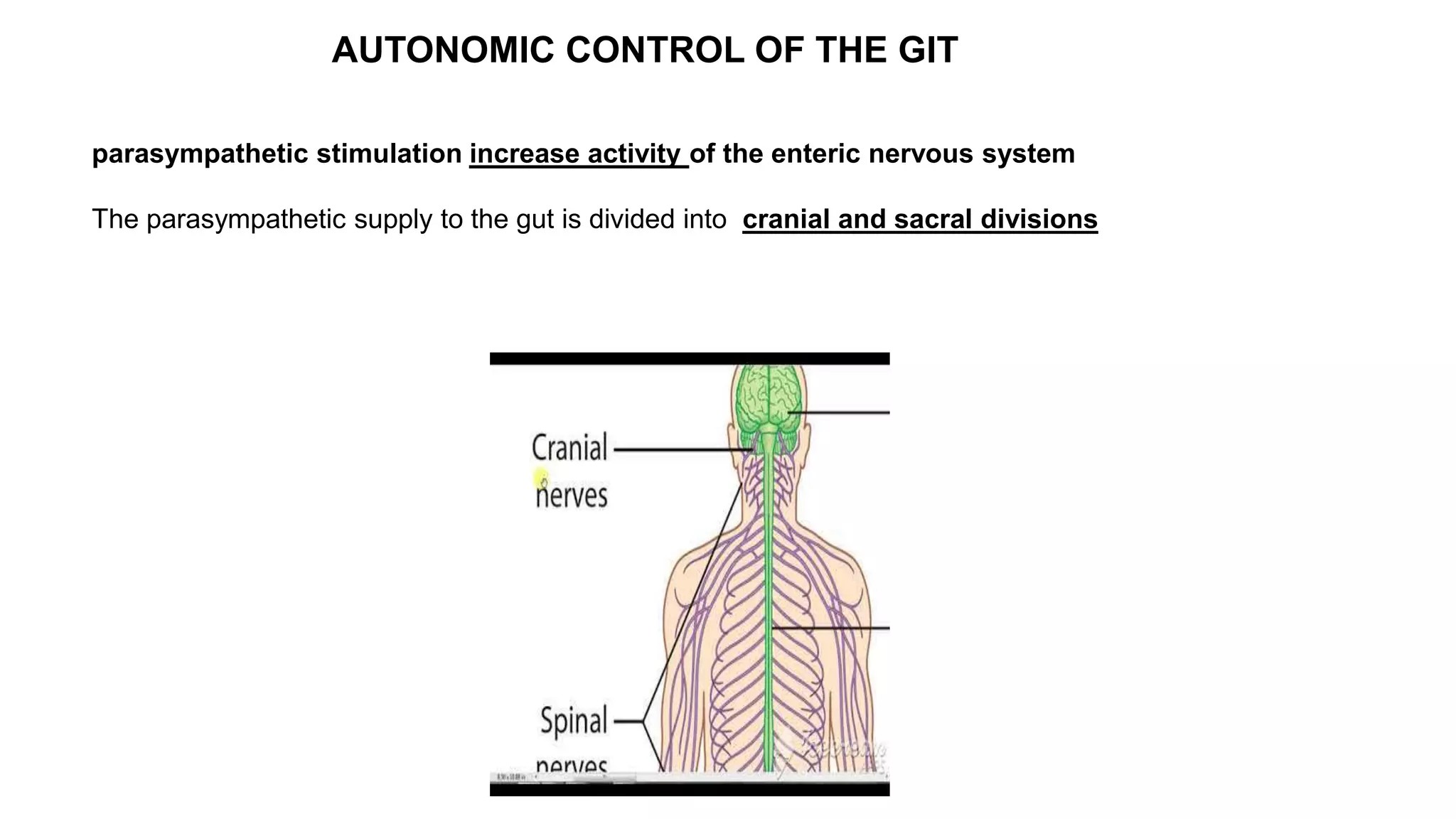

The gastrointestinal tract has its own nervous system called the enteric nervous system. It contains around 100 million neurons located in the gut wall. This system controls gastrointestinal movements and secretion. It contains two main plexuses - the myenteric plexus between the gut muscles and the submucosal plexus in the submucosa. The myenteric plexus mainly controls movements while the submucosal plexus controls secretion and blood flow. The enteric nervous system communicates with the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems to regulate gastrointestinal functions.