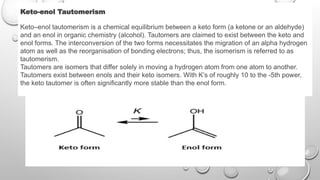

Enols are organic compounds featuring a hydroxyl group directly bonded to an alkene, serving as tautomers of carbonyl compounds, while enolates are their more reactive conjugate bases formed by deprotonation. Enolate formation occurs through the abstraction of alpha-hydrogens by strong bases, leading to their crucial role in various synthetic reactions, notably in aldol condensations. The document discusses the mechanisms of enol and enolate formation, their reactivity, and differences, emphasizing their importance in organic chemistry.