The document provides an overview of the endocrine system, including:

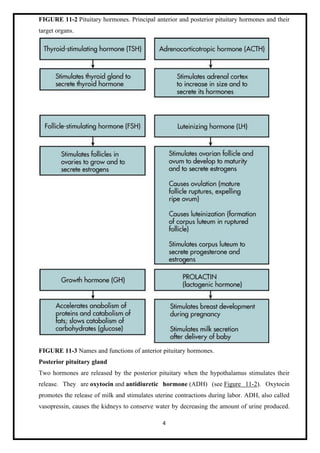

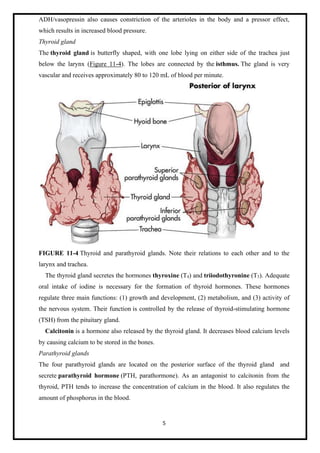

- The endocrine system is composed of ductless glands that secrete hormones directly into the bloodstream to regulate bodily functions like metabolism and growth.

- The major glands are the pituitary, thyroid, parathyroid, adrenal, pancreas, ovaries/testes, thymus, and pineal glands.

- Common endocrine disorders affect hormone balance and can cause symptoms ranging from fatigue and weight changes to neurological or organ issues depending on the gland impacted.