This document discusses various gas power cycles used in engines. It describes the Otto, Diesel, dual, and Brayton cycles. The Otto cycle models spark ignition engines using four processes: isentropic compression, constant volume combustion, isentropic expansion, and constant volume exhaust. The Diesel cycle also uses four processes but replaces constant volume combustion with constant pressure combustion. The dual cycle combines aspects of the Otto and Diesel cycles. The Brayton cycle models gas turbines using constant pressure processes. Real examples of engines using these cycles are also provided.

![=49

=4.49%

3. The compression ratio o f an air standard dual cycle is 12 and the maximum

pressure on the cycle is limited to 70bar. Th e pressure and temperature of the

cycle at the b eginning of compression process are 1bar a nd 300K. Calculate the

thermal efficiency and M ean Effective Pressure. Assume cylinder bore = 250mm,

Stroke length = 300mm, Cp=1.005K J/Kg K, Cv=0.718KJ/Kg K.

Given data:

Assume Qs1 = Qs2

Compression ratio (r) = 12

Maximum pressure (P3) = (P4) = 7000 KN/m2

Temperature (T1) = 300 K

Diameter (d) = 0.25m

Stroke length (l) = 0.3m

To find:

Dual cycle efficiency (ηdual)

Mean Effective Pressure (P m)

Solution:

By Process 1-2:

= [r]γ-1

300[12

T2 = 810.58K

P2 = 3242.3KN/m2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eded8073dpvpnotes-180418075812/75/ED8073-dpvp_notes-17-2048.jpg)

![By process 2-3:

T3 = 1750K

Assuming Qs1 = Qs2

mCv[T3-T2] = mCp[T4-T3]

0.718 [1750-810.58] = 1.005 [T4-1750] T4 = 2421.15K

By process 4-5:

We know that, = 1.38

T5 = 1019.3K](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eded8073dpvpnotes-180418075812/75/ED8073-dpvp_notes-18-2048.jpg)

![Heat supplied Qs = 2

Q s = 1349KJ/Kg

Heat rejected

T1

]

Qr

= 516.45 KJ/Kg

ηdual

η dual = 61.72%

Stroke volume (Vs) =

Vs = 0.0147m3

Mean Effective Pressure (Pm)

= 832.58/0.0147

Pm = 56535 KN/m2

4. A diesel engine

operating

30cmstroke.the clearance volu

me is the air standard

efficiency.

an air standard

diesel cycle has

20cm bore

and

420cm3

.if the fuel is injected at

5%

of the

stroke,find

Given Data:-

Bore diameter (d) =20cm=0.2mk

Stroke, (l) =30cm=0.3m

Clearance volume, (v2 ) =420cm3

=420/1003

= m3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eded8073dpvpnotes-180418075812/75/ED8073-dpvp_notes-19-2048.jpg)

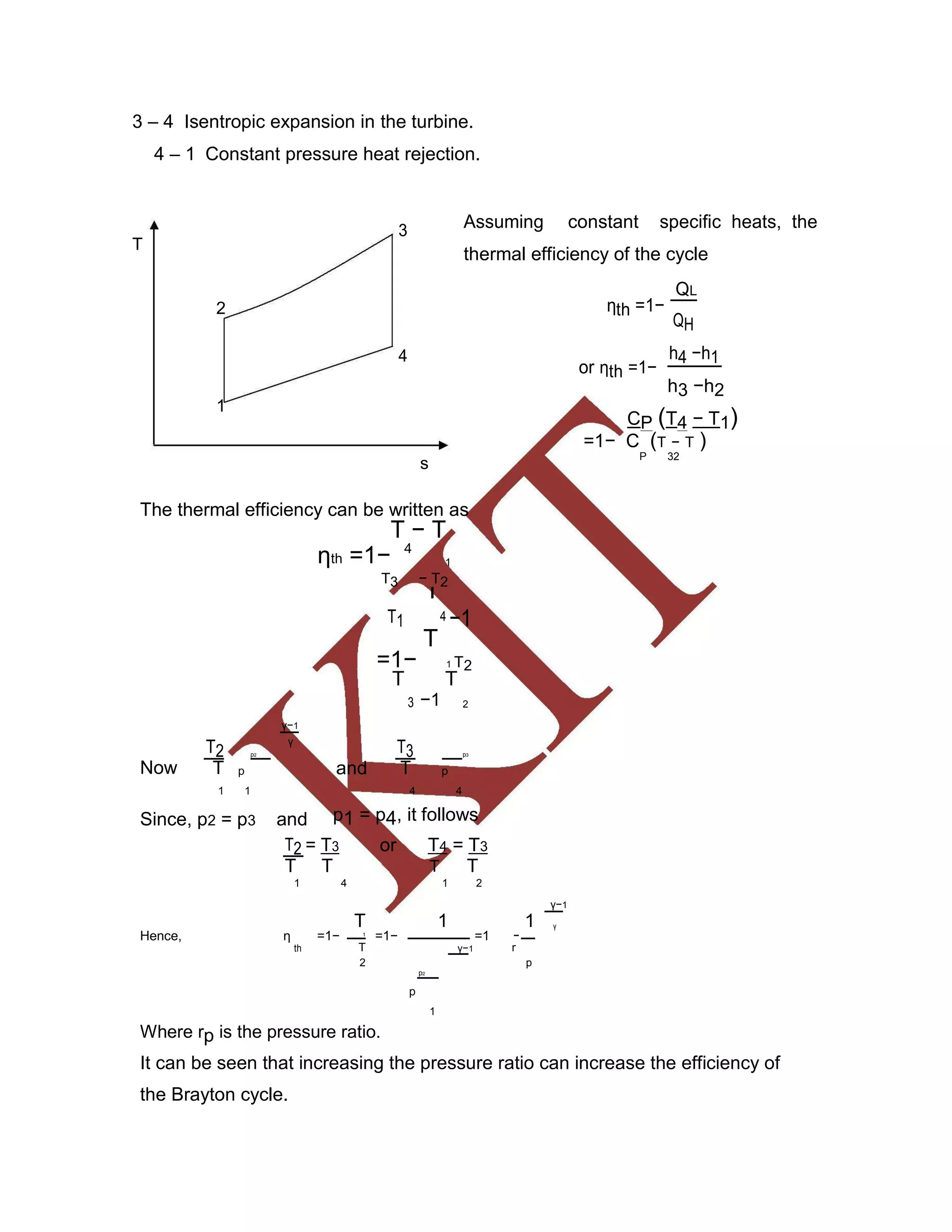

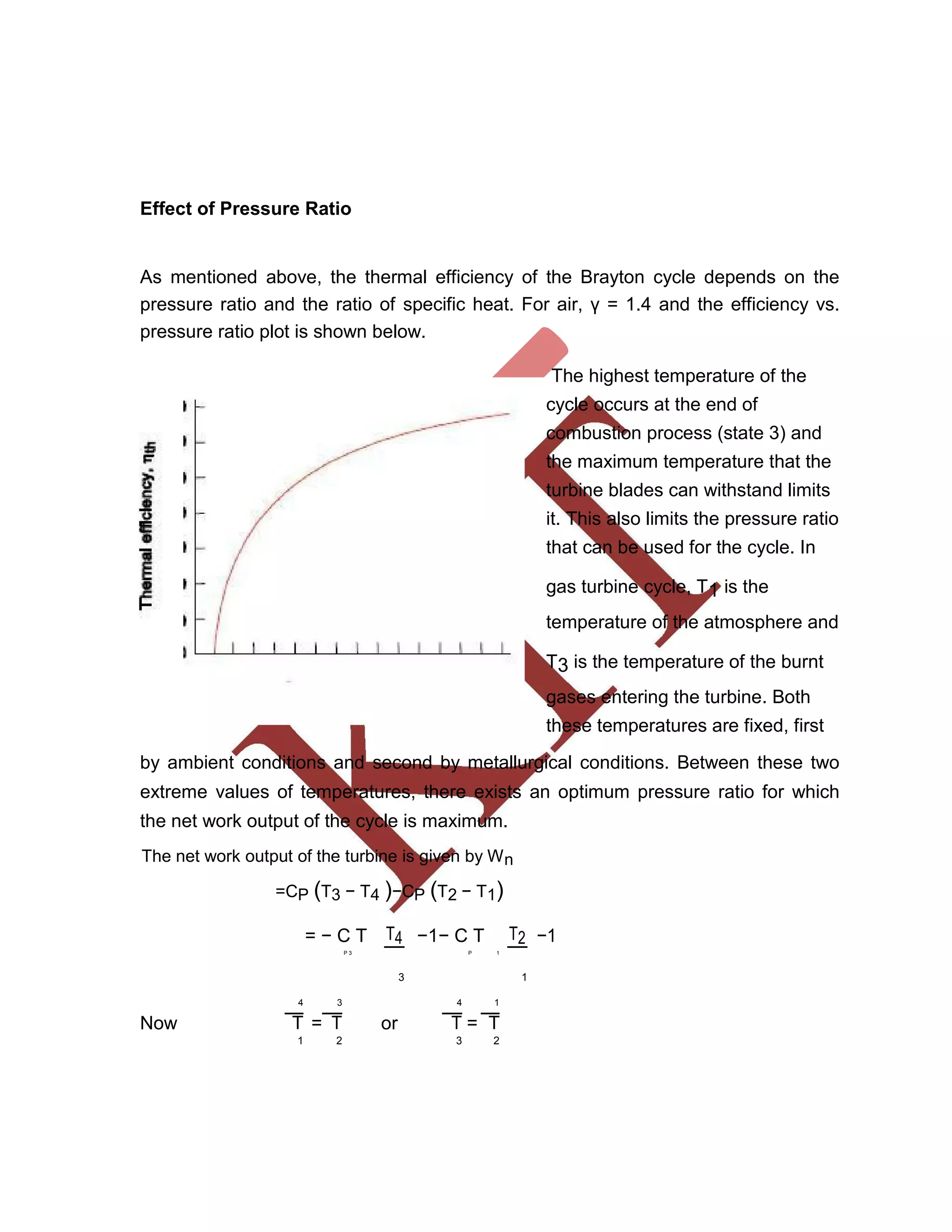

![∴ W = −C T T1 −1 − C T

T

2 −1

n P 3 P 1

2 1

γ−1

1 p2 γ

= − C T −1 − C T −1

P 3 γ−1 P 1

p

p 2 1

1

= − C T 1 −1 −C T (r ) γ

γ

−1

−1

P 3 γ−1 P 1 P

(rP ) γ

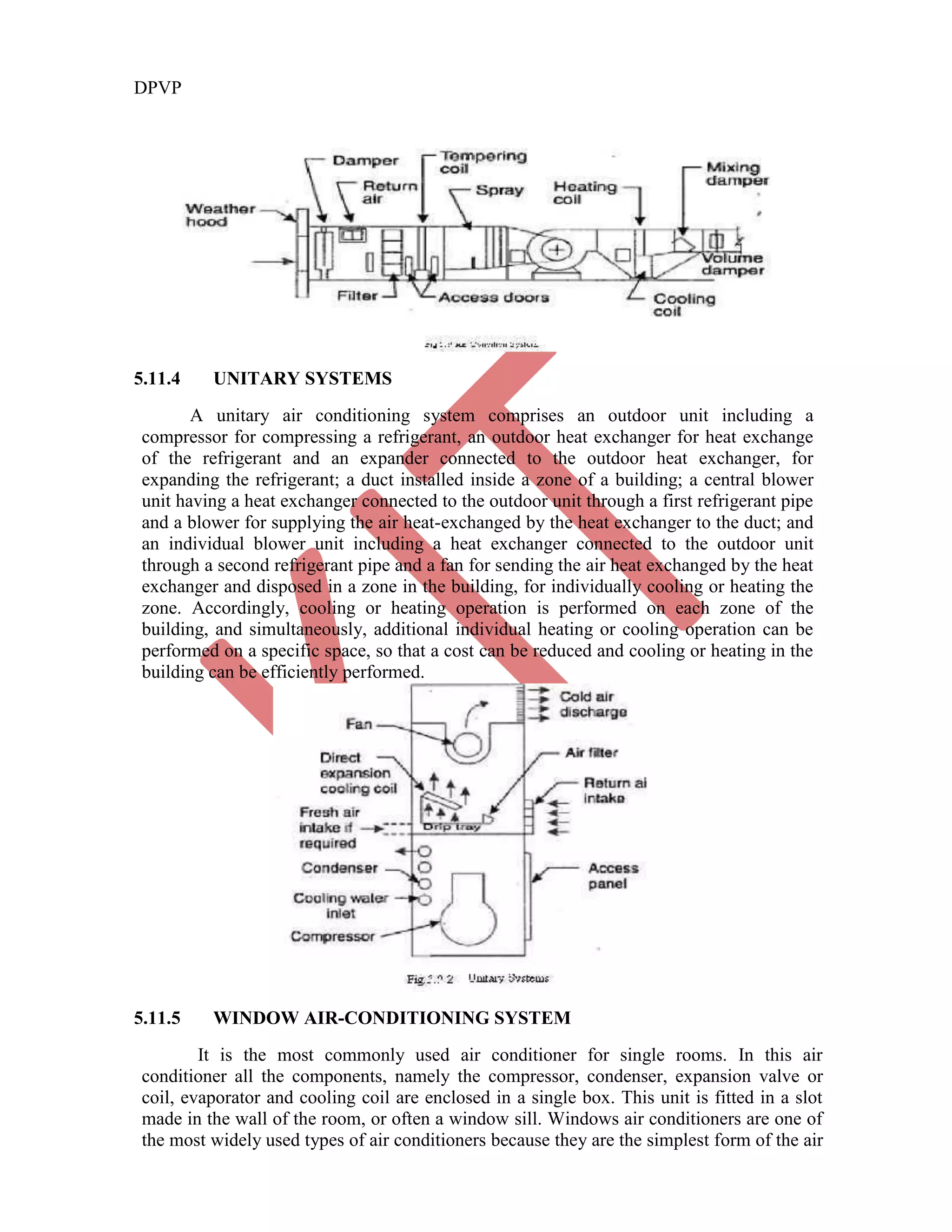

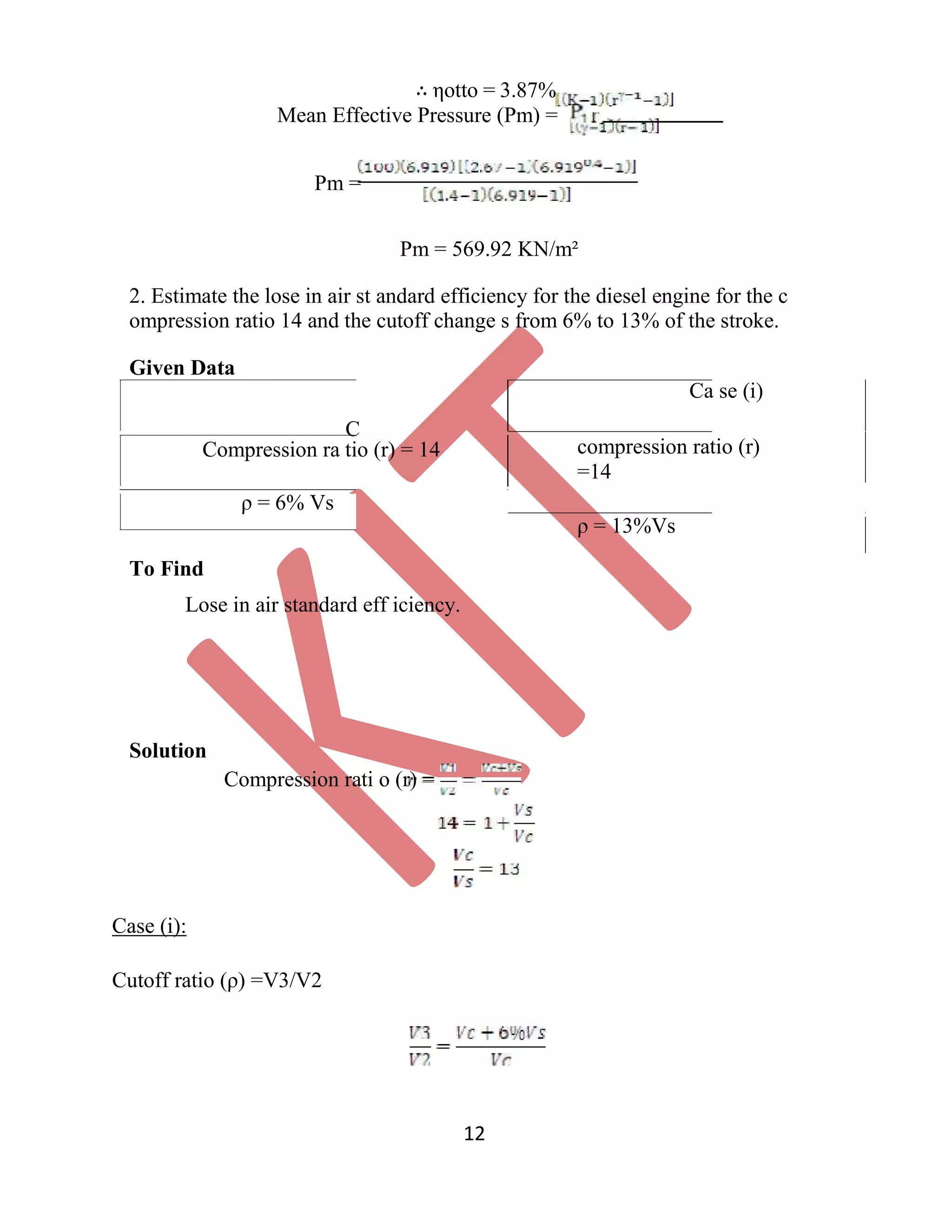

The optimum pressure ratio is obtained by differentiating the net work with respect

to pressure ratio, rP and putting the derivative as zero.

Let

γ −1

γ =n

1

Wn = −CP T3 rP n −1 −CP T1 [(rP )

n

−1]

( )

or dWn= −CP T3 [−n rP

−n−1

]−CP T1 [n rP

n−1

]

dr

P

or 0 =C T nr

−n−1

−C T n r

n−1

P 3 P P 1 P

or T nr−n−1 = T n r

n−1

3 P 1 P

or r( − n−1) − (n −1) = 1

TP

3

or r−2n = 1

P

T3

T

or r2n

=

3

P

T1

T 1

3 2n

i.e. (rP )optimum =

T

1

T3 2

γ (

γ −1

)

or (

r

P )optimum

=

T

UNIT –V

PIPING](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eded8073dpvpnotes-180418075812/75/ED8073-dpvp_notes-71-2048.jpg)