The document is an educational workbook on the basic principles of internal combustion engines. It was prepared by Engineer Nazar Faisal Ouda Al-Obaidi for the Technical Training Institute's Machinery and Equipment Department. The workbook contains information on key concepts related to internal combustion engines like:

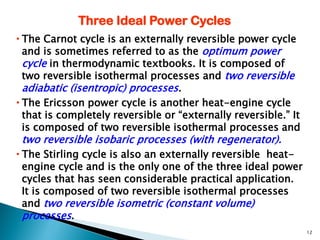

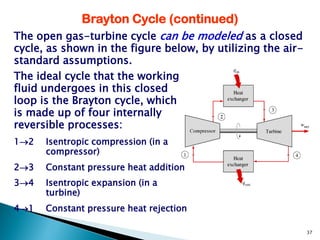

- Conversion of thermal energy to mechanical energy in heat engines through thermodynamic power cycles.

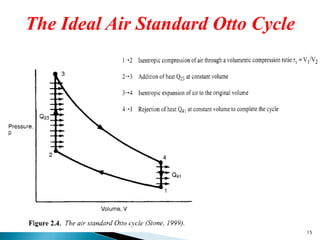

- Analyzing engine cycles using pressure-volume and temperature-entropy diagrams.

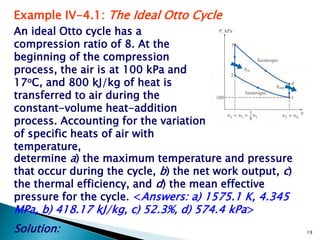

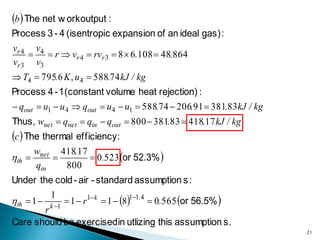

- Characterizing the ideal Otto cycle that models spark-ignition engines and the ideal Diesel cycle that models compression-ignition engines.

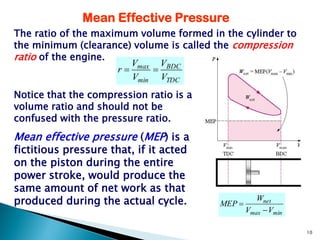

- Explaining engine parameters like compression ratio, mean effective pressure, and thermal efficiency.

![• Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC) is a measure of fuel

efficiency within a shaft reciprocating engine. It is the rate

of fuel consumption divided by the power produced. Specific

fuel consumption is based on the torque delivered by the

engine in respect to the fuel mass flow delivered to the engine.

Measured after all parasitic engine losses is brake specific fuel

consumption [BSFC] and measuring specific fuel consumption

based on the in-cylinder pressures (ability of the pressure to do

work) is indicated specific fuel consumption [ISFC].

94](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/random-120819095427-phpapp02/85/slide-94-320.jpg)