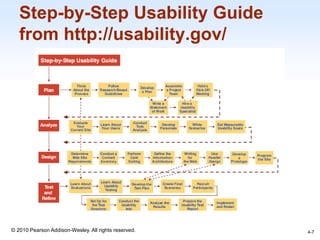

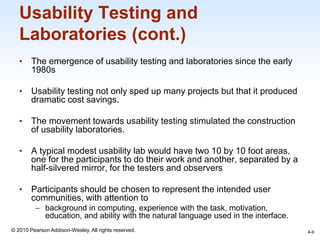

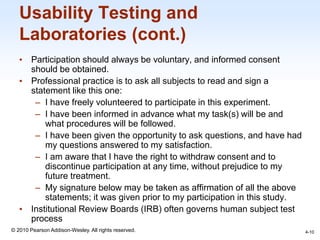

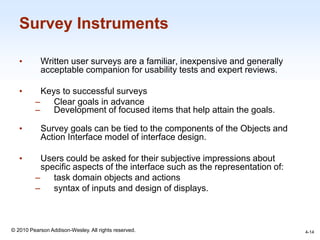

This document discusses methods for evaluating interface designs from the book "Designing the User Interface" by Ben Shneiderman and Catherine Plaisant. It describes expert reviews, usability testing, surveys, acceptance tests, and evaluating interfaces during active use to identify issues and improve designs. Evaluation methods range from informal reviews to rigorous multi-phase testing depending on the project. Gathering user feedback is important throughout the design and development process.