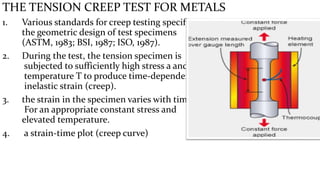

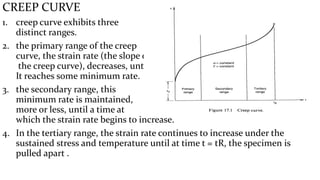

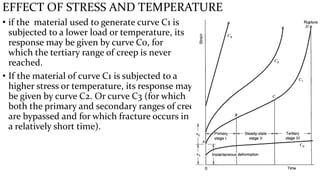

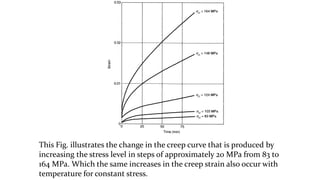

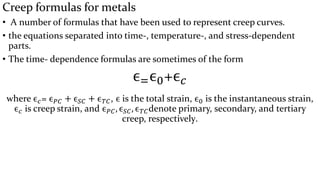

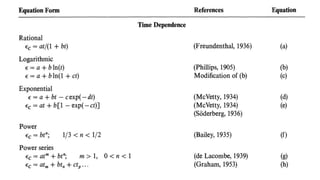

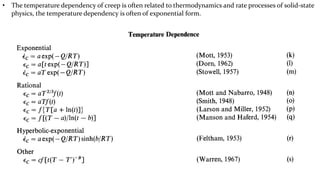

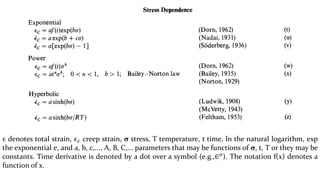

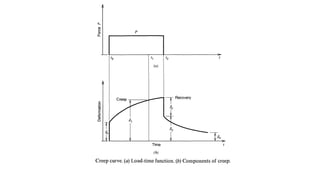

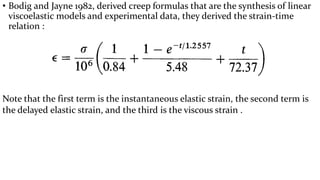

Creep is defined as time-dependent inelastic strain under sustained load and elevated temperature. Creep testing involves subjecting metal specimens to high stress and temperature to produce time-dependent inelastic strain. The creep curve exhibits three stages: primary, secondary, and tertiary. Creep is affected by stress, temperature, and time based on empirical formulas. Creep behavior is more complex for nonmetals like concrete and wood due to additional factors like aging, moisture content, and anisotropy. Creep testing and modeling helps understand material deformation over long periods under load.