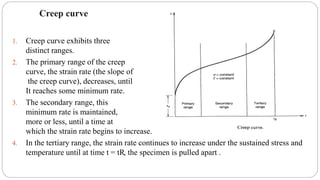

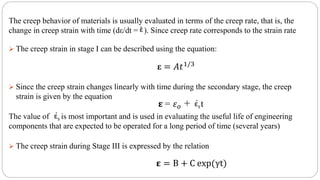

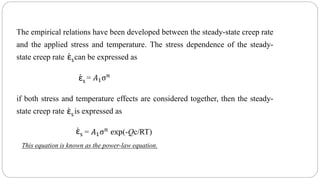

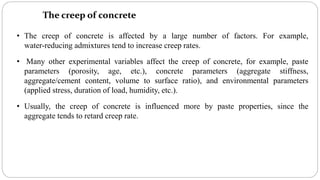

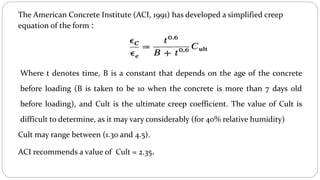

This document discusses creep, which is the time-dependent deformation of materials under sustained stress and elevated temperature. It provides background on creep testing and defines the three stages of creep: primary, secondary, and tertiary. Equations to describe creep behavior and the effect of stress and temperature on creep curves are presented. Creep properties of metals, nonmetals like concrete, and factors that influence concrete creep are examined through examples. The document is authored by Salih Khudair for a class on the theory of elasticity and references additional sources on experimental techniques and mechanics of materials.

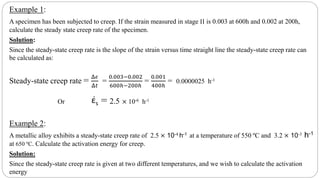

![The temperature need to be expressed in degrees K. therefore 550ºC =550+273=823K and

650ºC =650+273=923K. Substituting the appropriate values into this equation at those temperature, we obtain

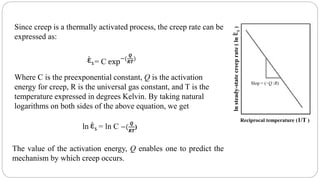

= C exp(-Q/RT)…… (Mott, 1953)

3.2 ×10-3 h-1 = C exp(- 𝑄

8.314 j mol−1 K−1×(923𝐾)

)

2.5 ×10-3 h-1 = C exp(- 𝑄

8.314 j mol−1 K−1 ×(823𝐾)

)

Dividing the above equations with each other, we get :

3.2 ×10−3 h−1

2.5 ×10−3 h−1 = exp[ -

𝑄

8.314 j mol−1 K−1 (

1

923

-

1

823

)]

1.28 ×10 h-1 = exp[ -

𝑄

8.314 j mol−1 K−1 ( −1.316 10-4 )]

Taking natural logarithms on both sides

Ln(1.28 ×10) = [(-

𝑄

8.314

)(−1.316 ×10-4 )]

2.55= Q ×1.583 ×10-5

Q =1.611 ×105 J mol−1, that is , 161 kJ mol−1

.

εs](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/creepfinal123-181216094949/85/Creep-final-123-19-320.jpg)