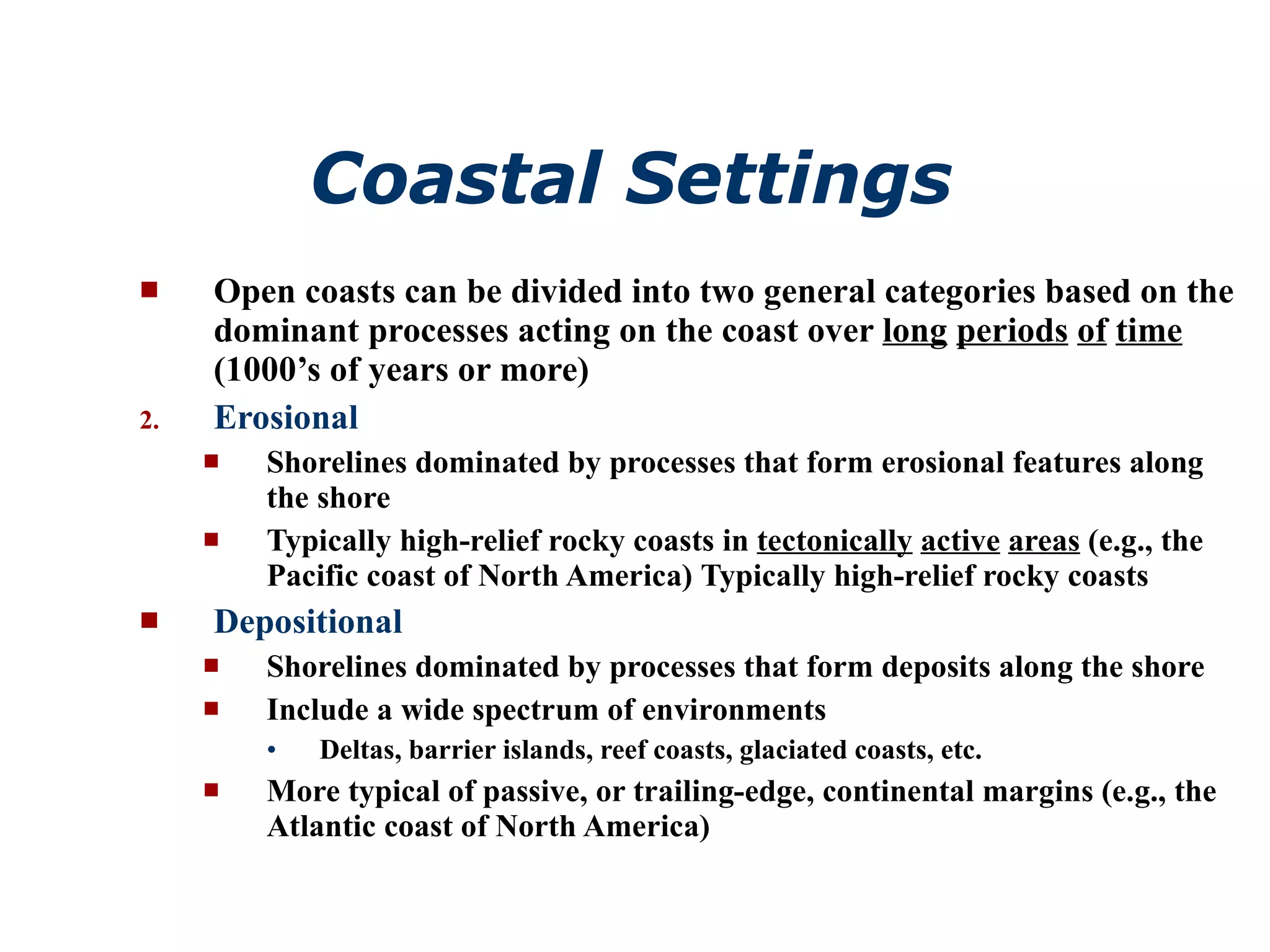

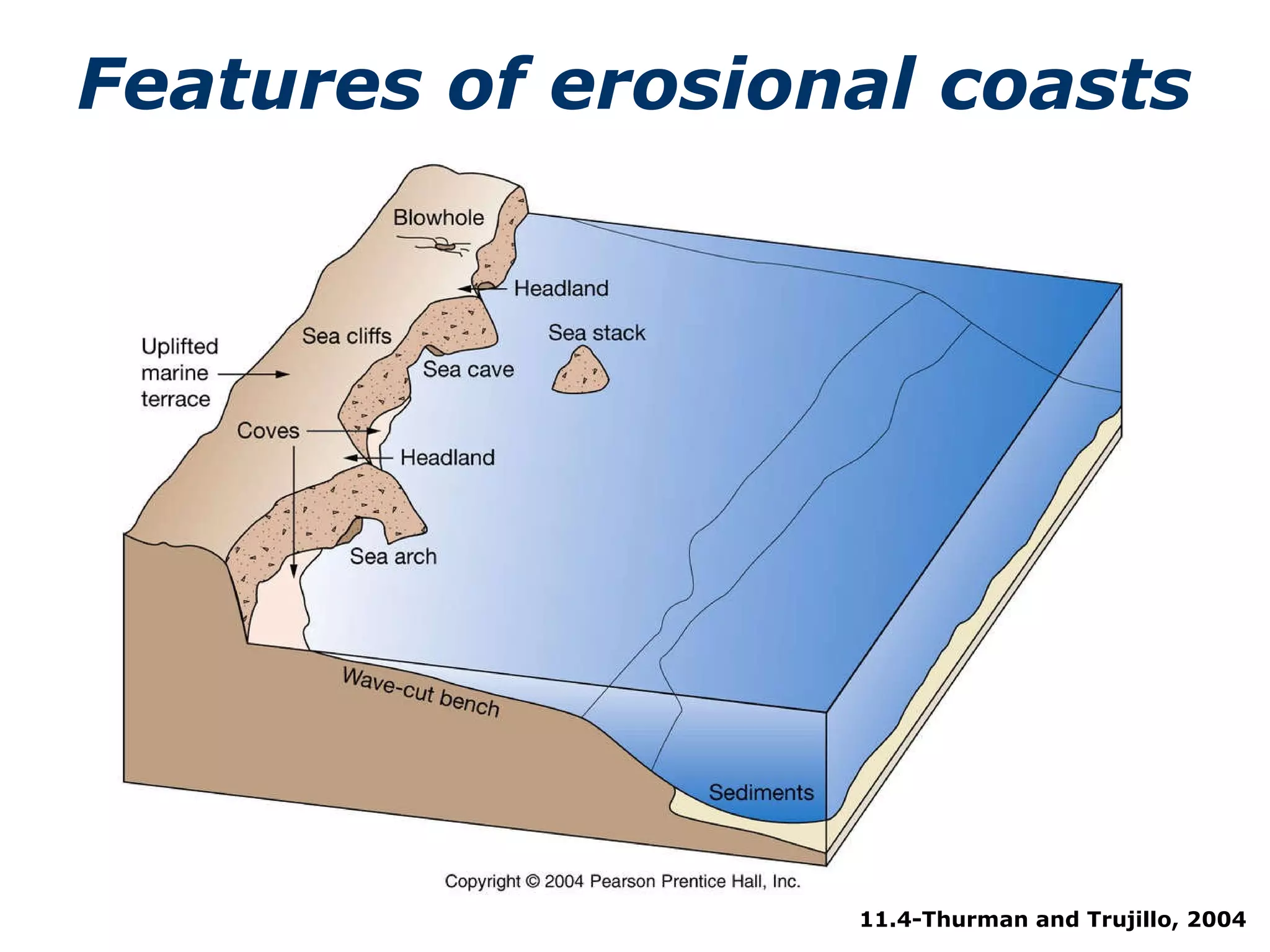

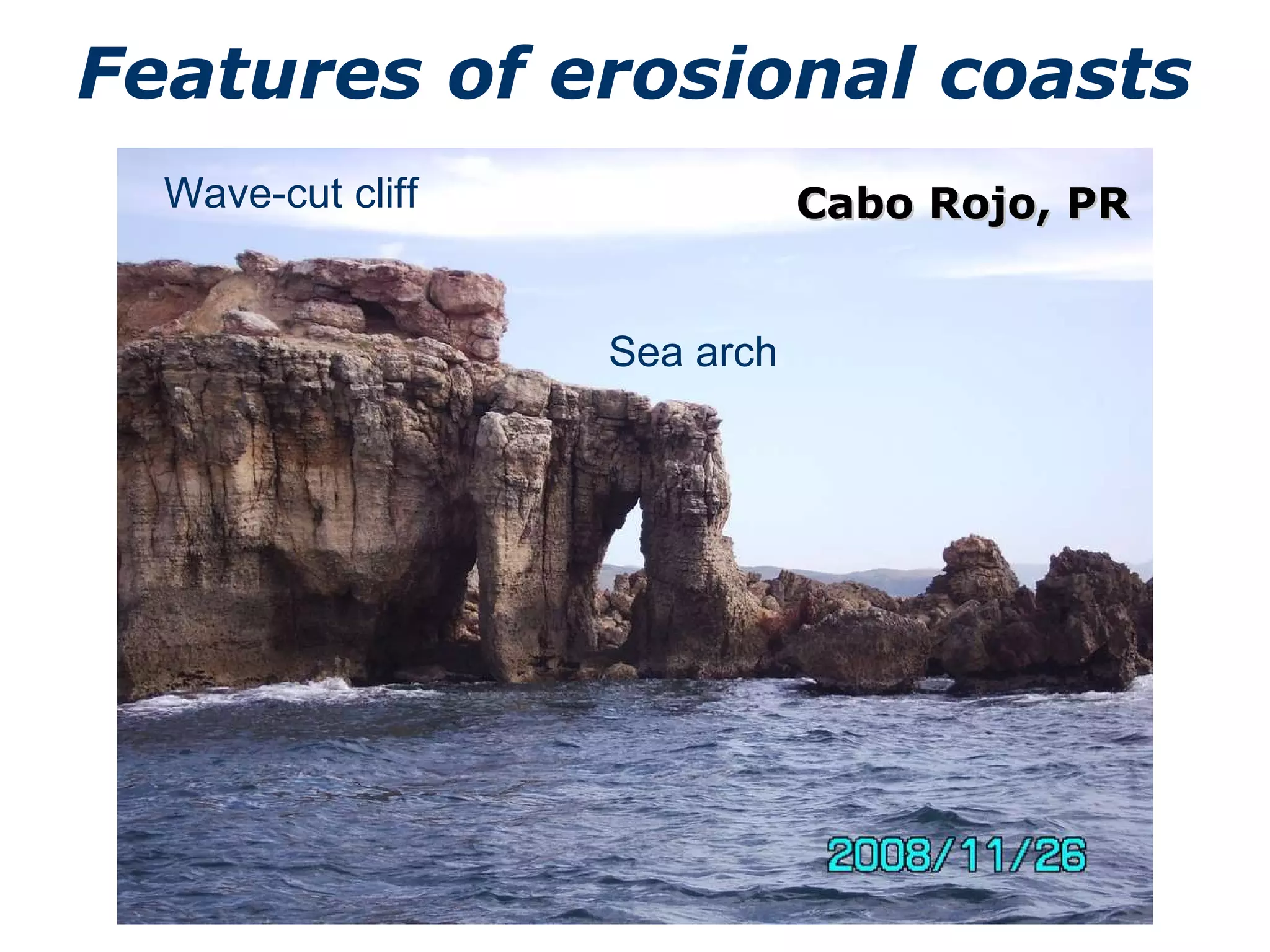

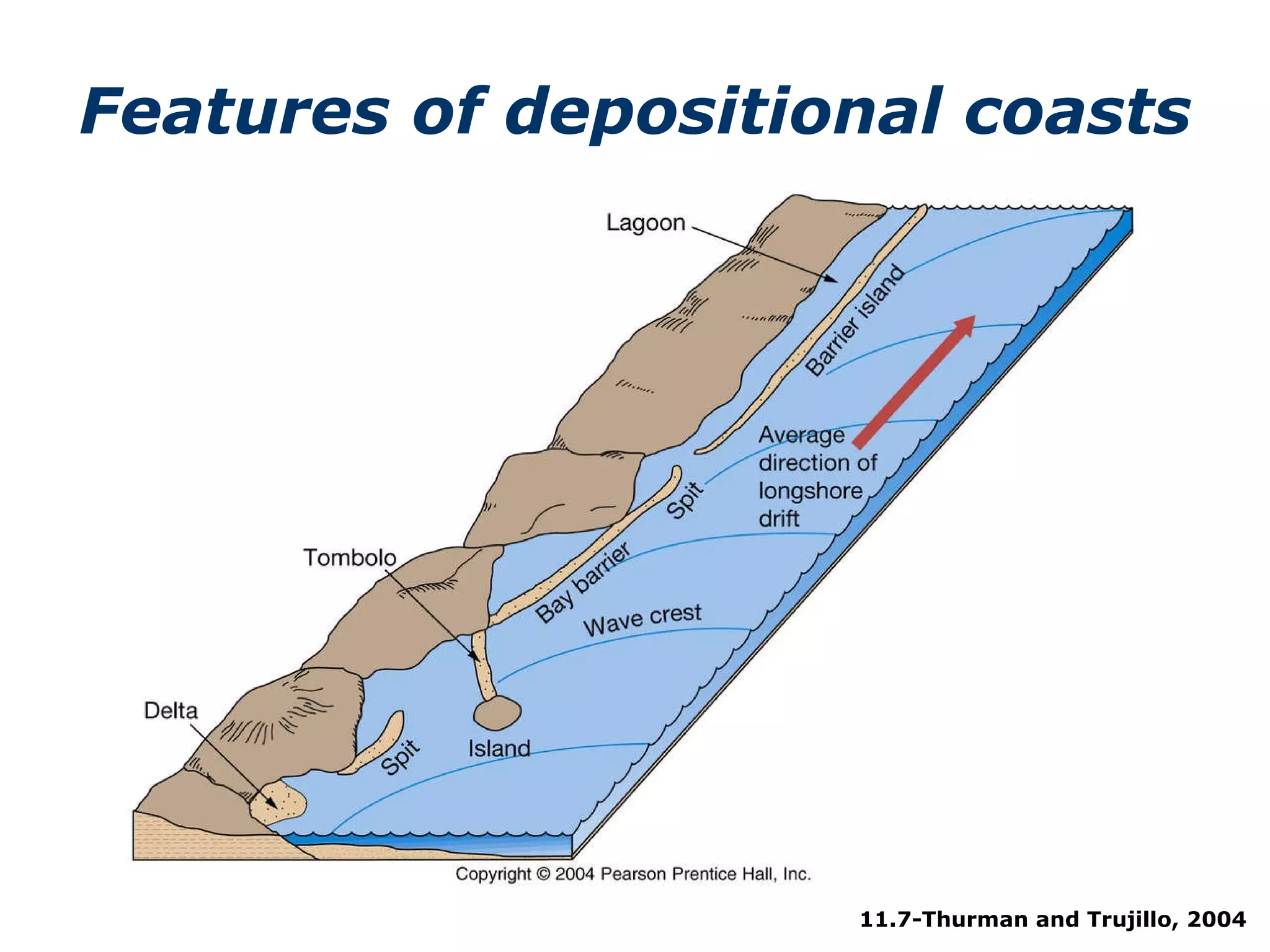

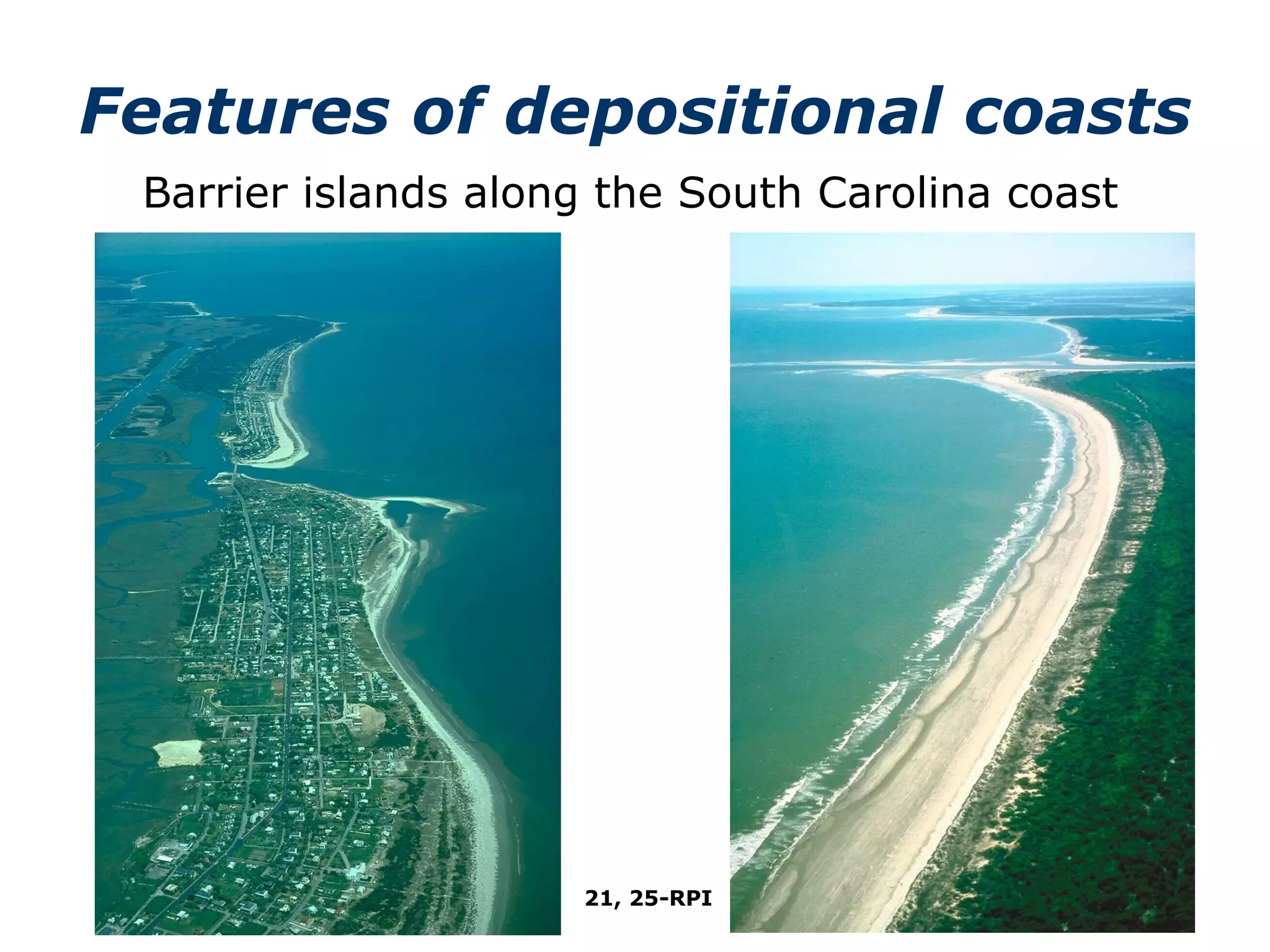

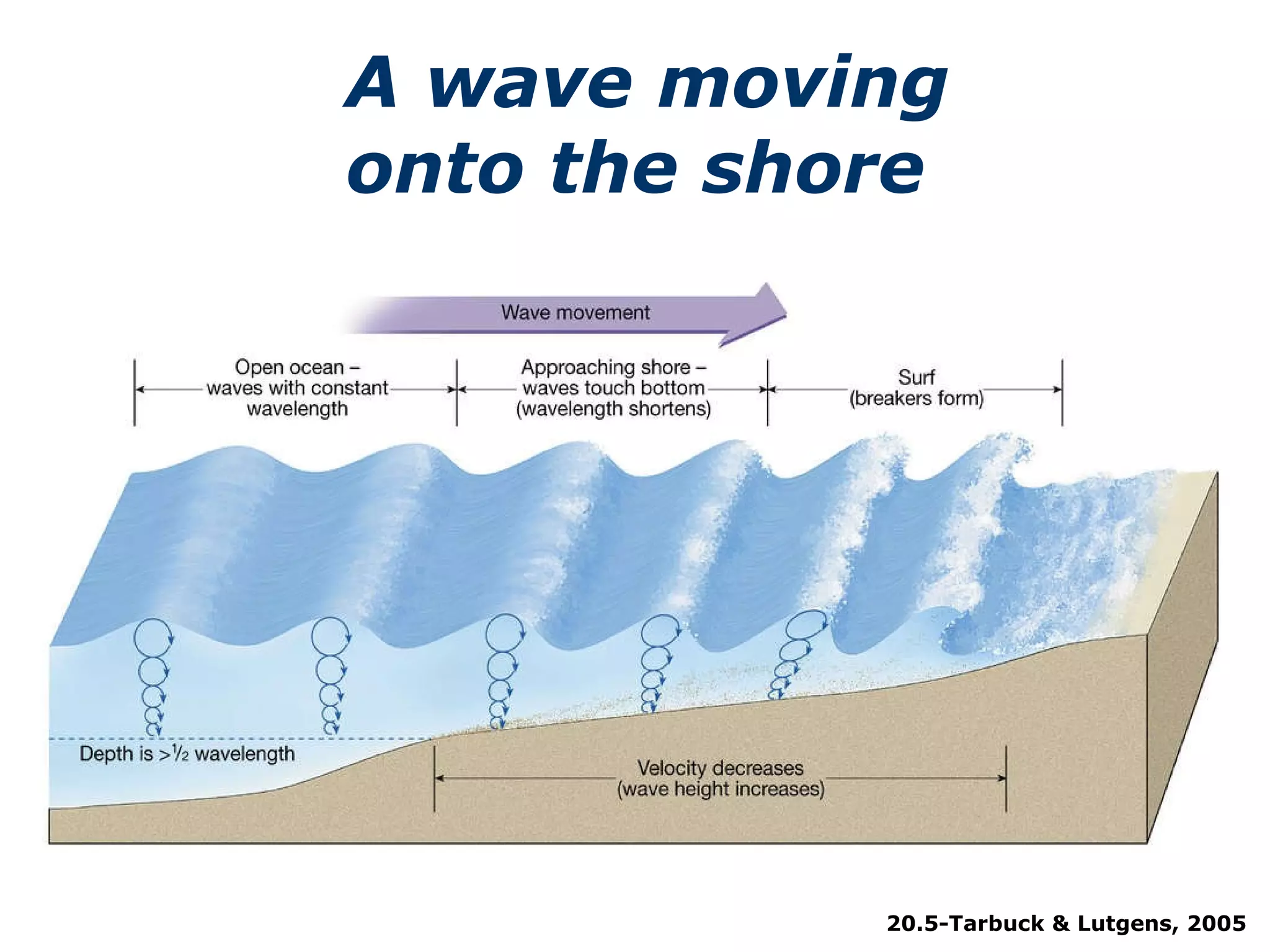

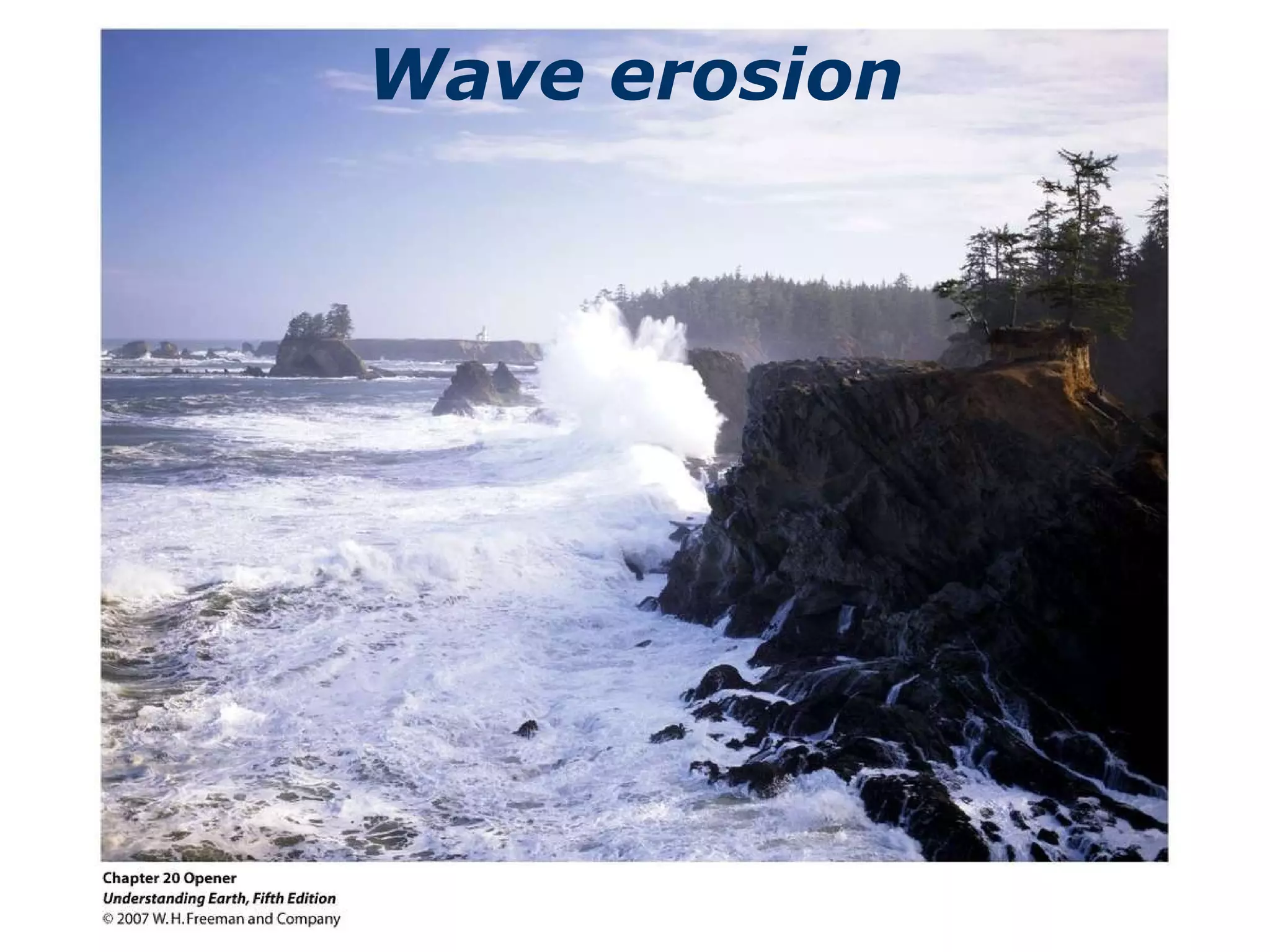

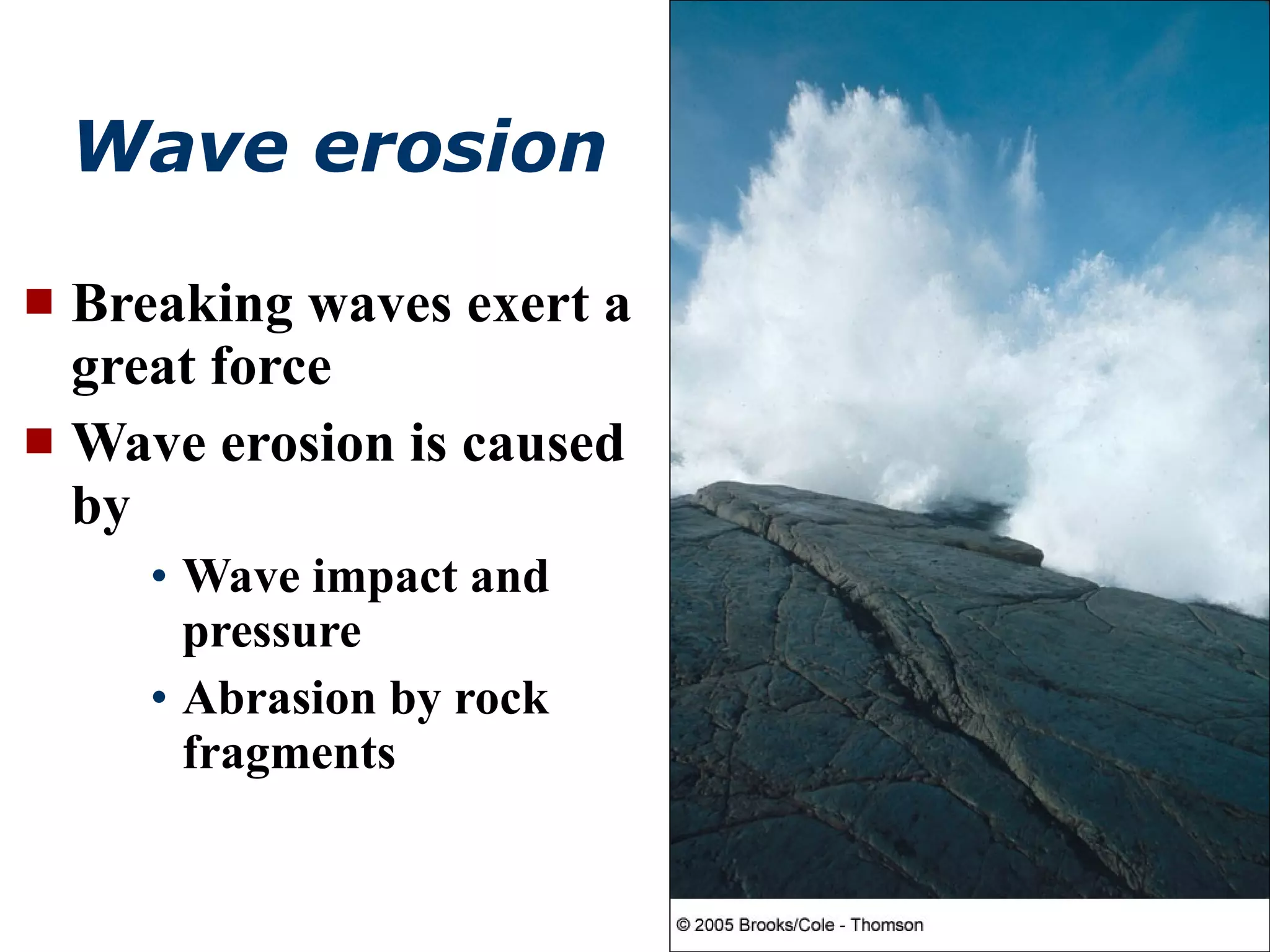

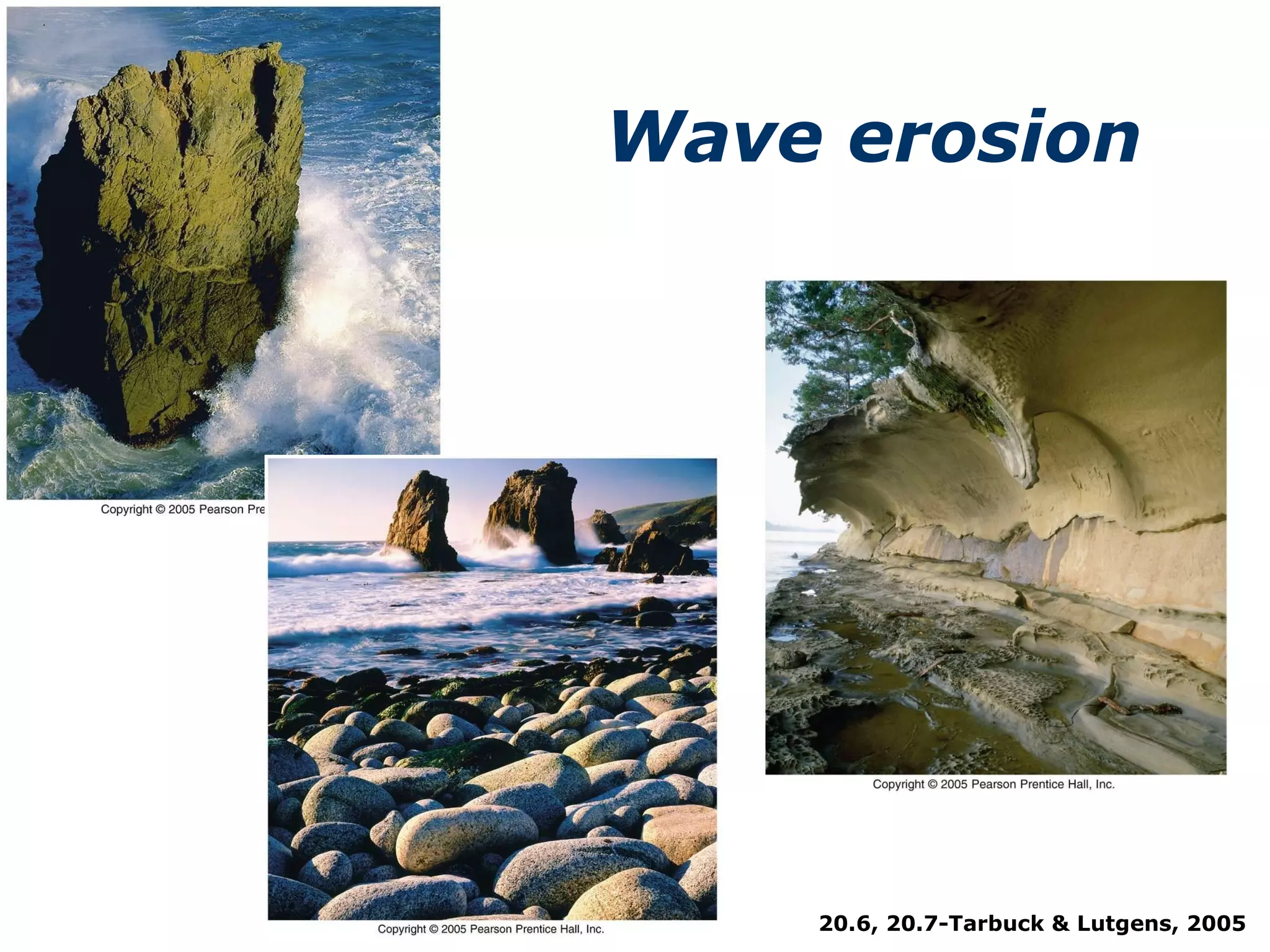

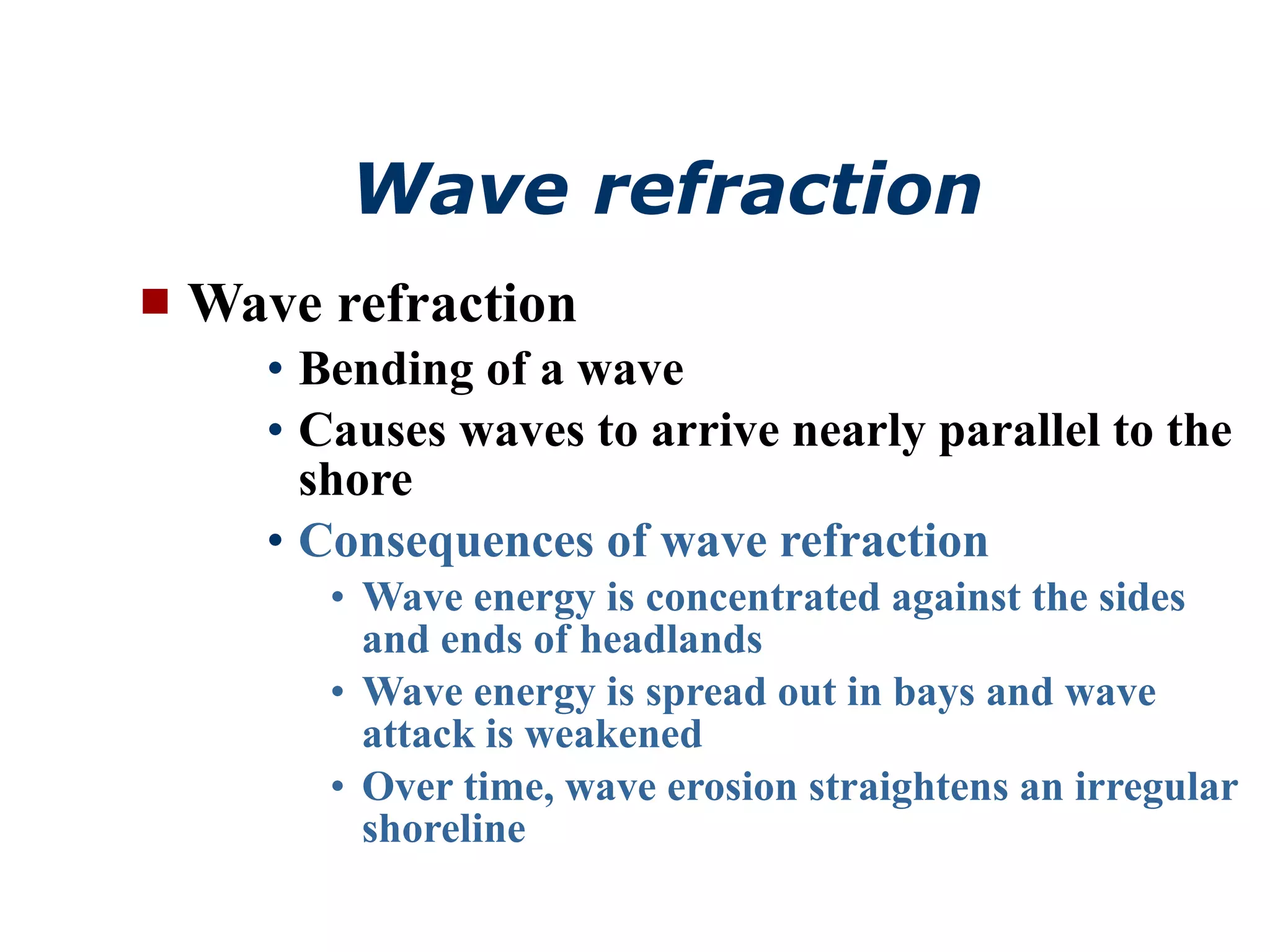

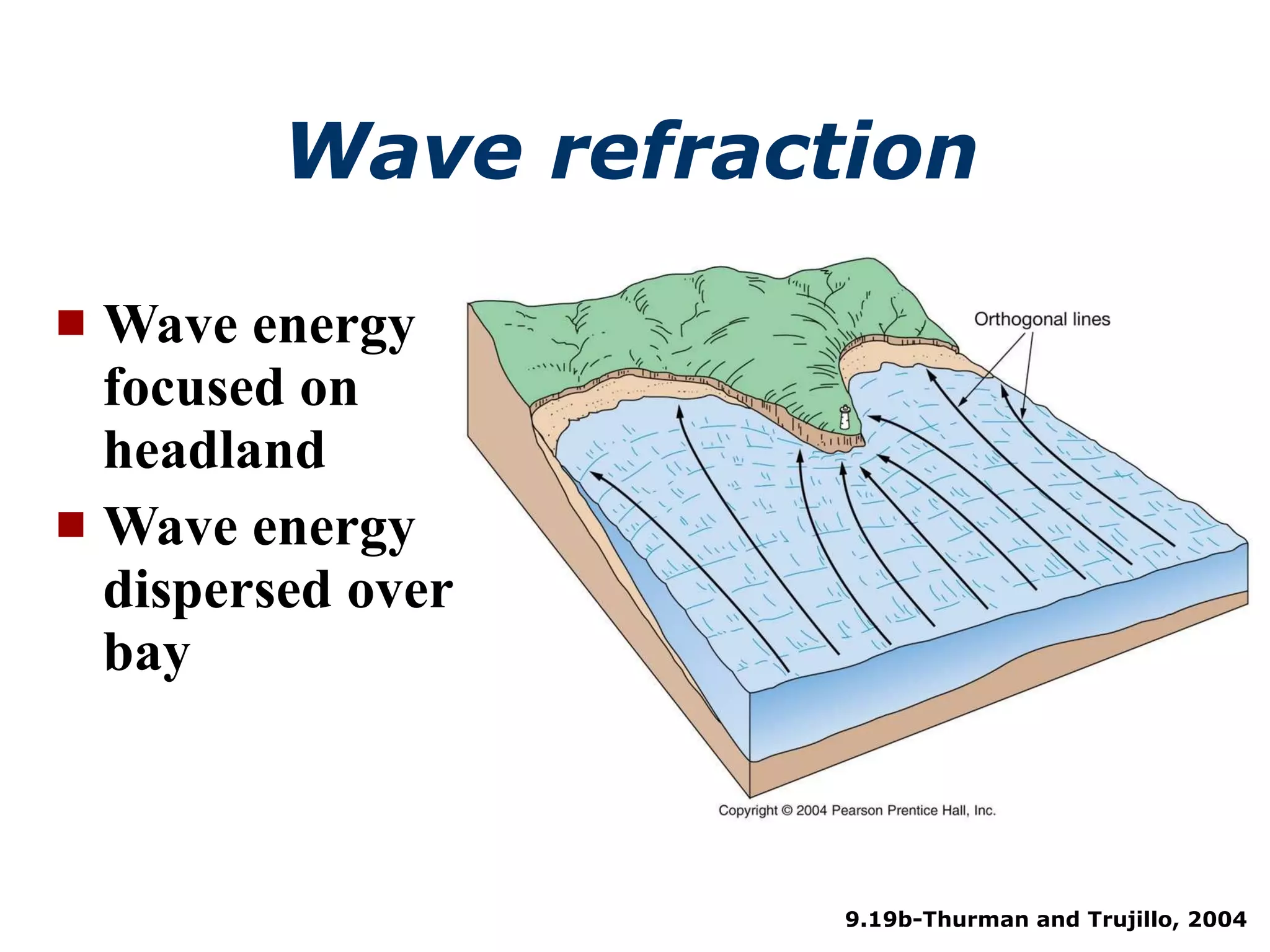

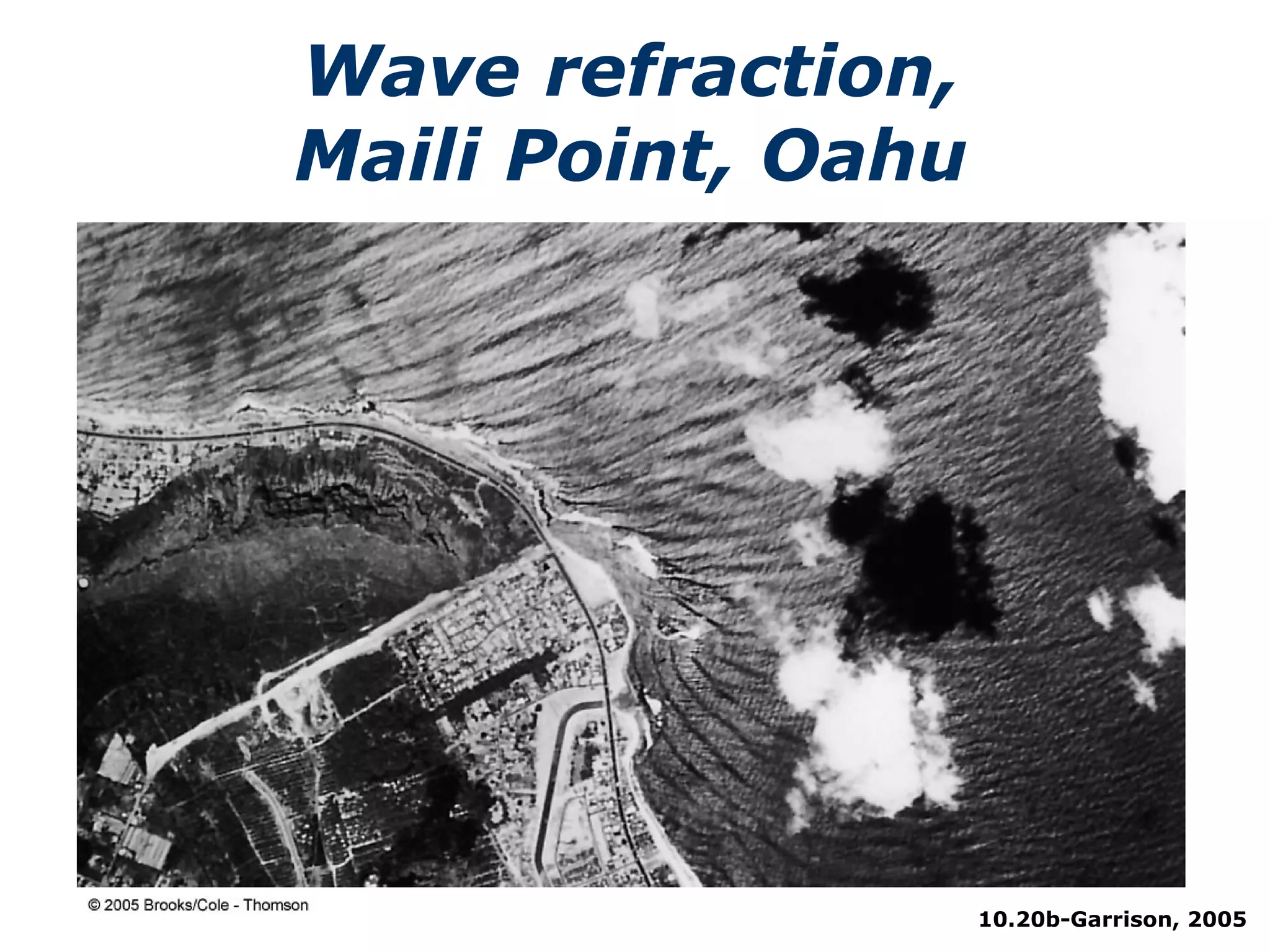

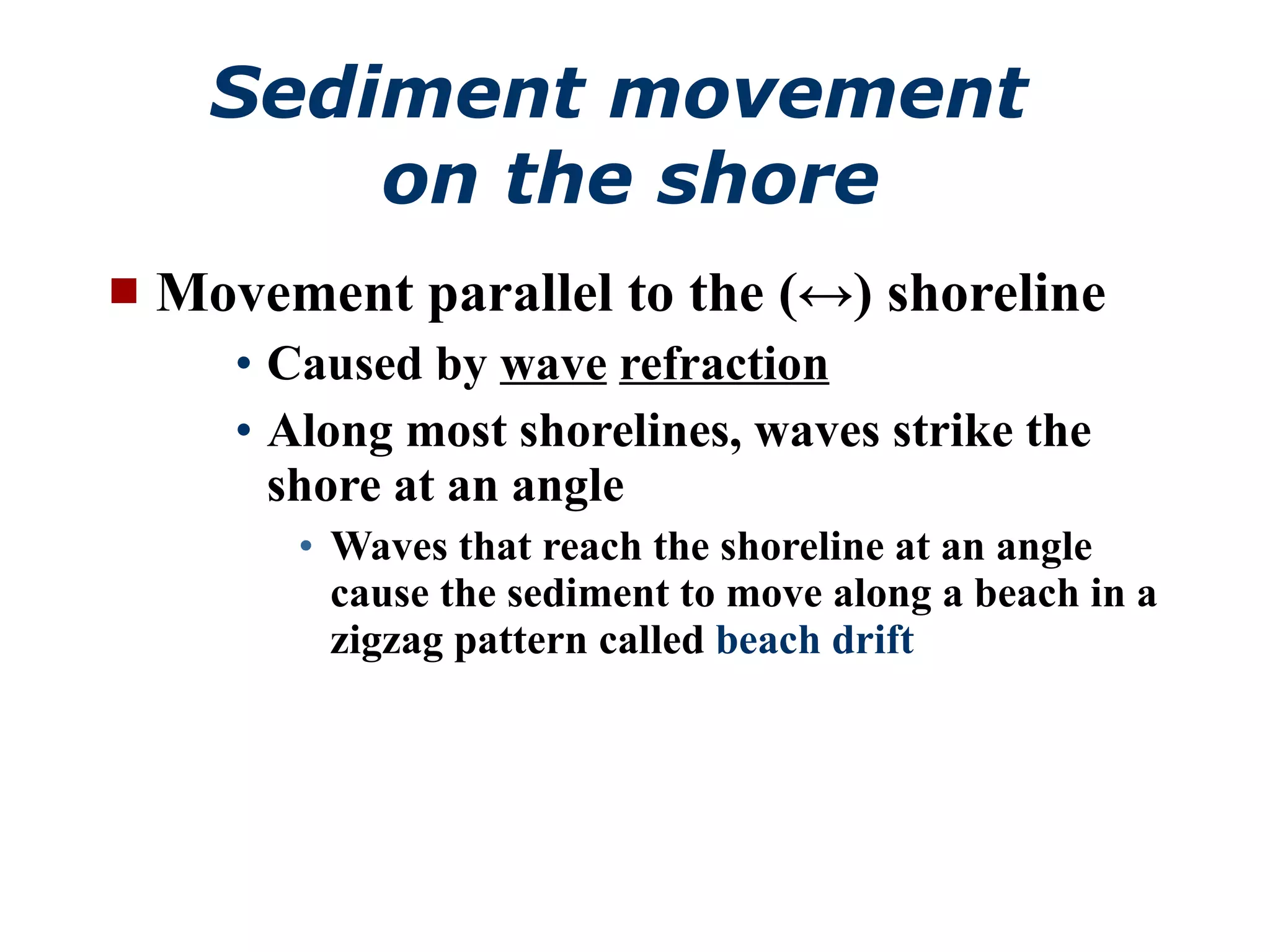

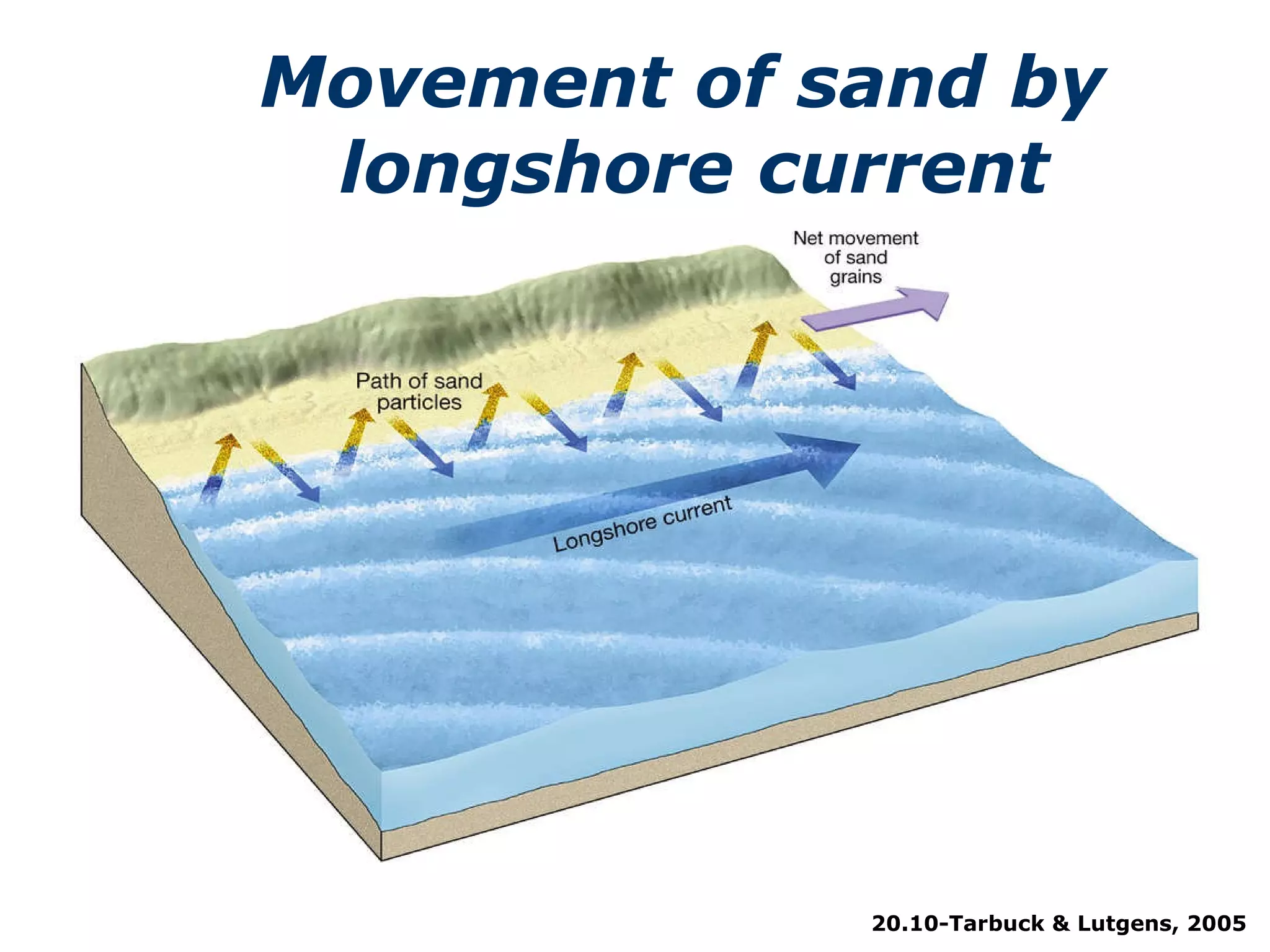

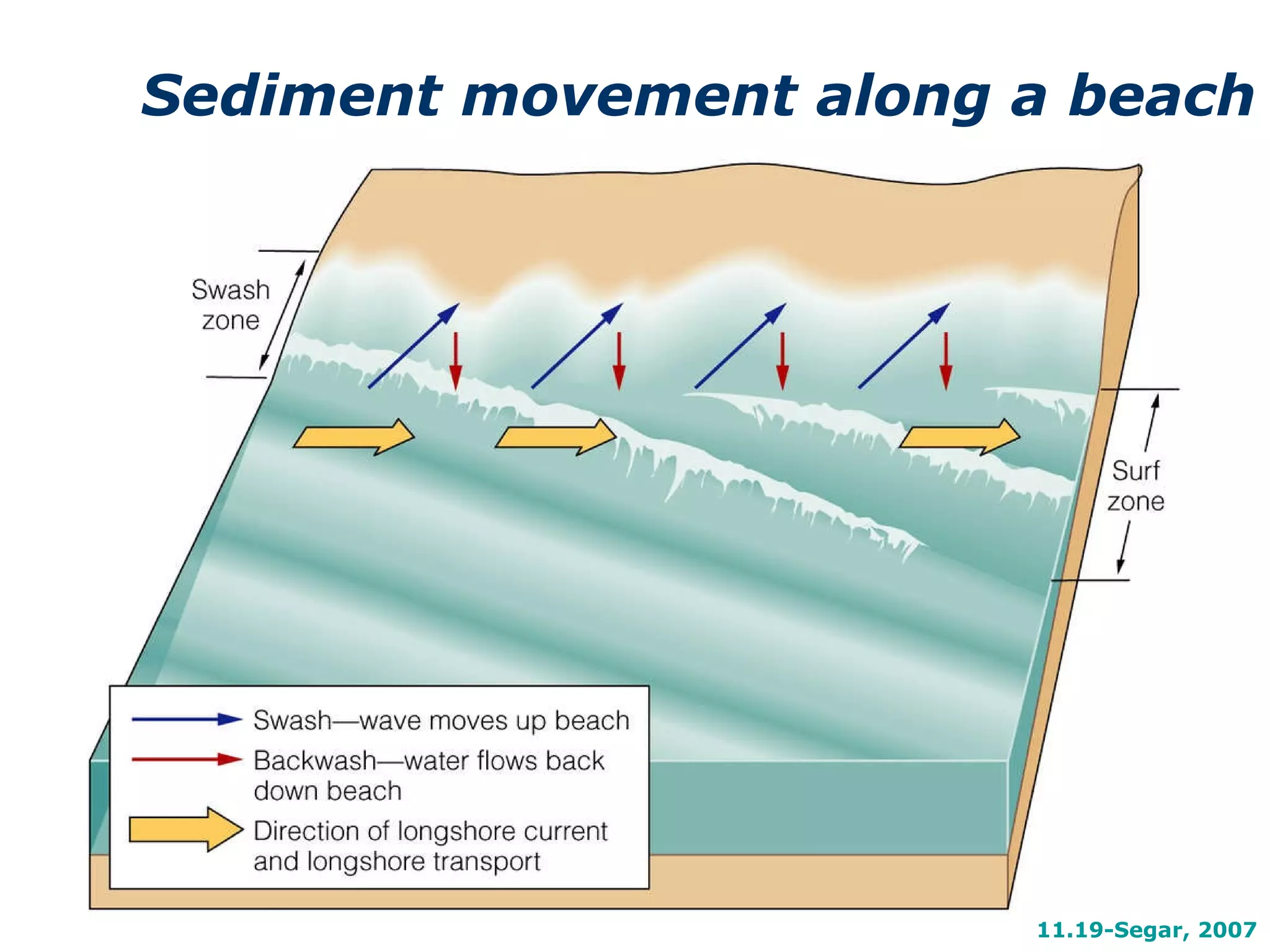

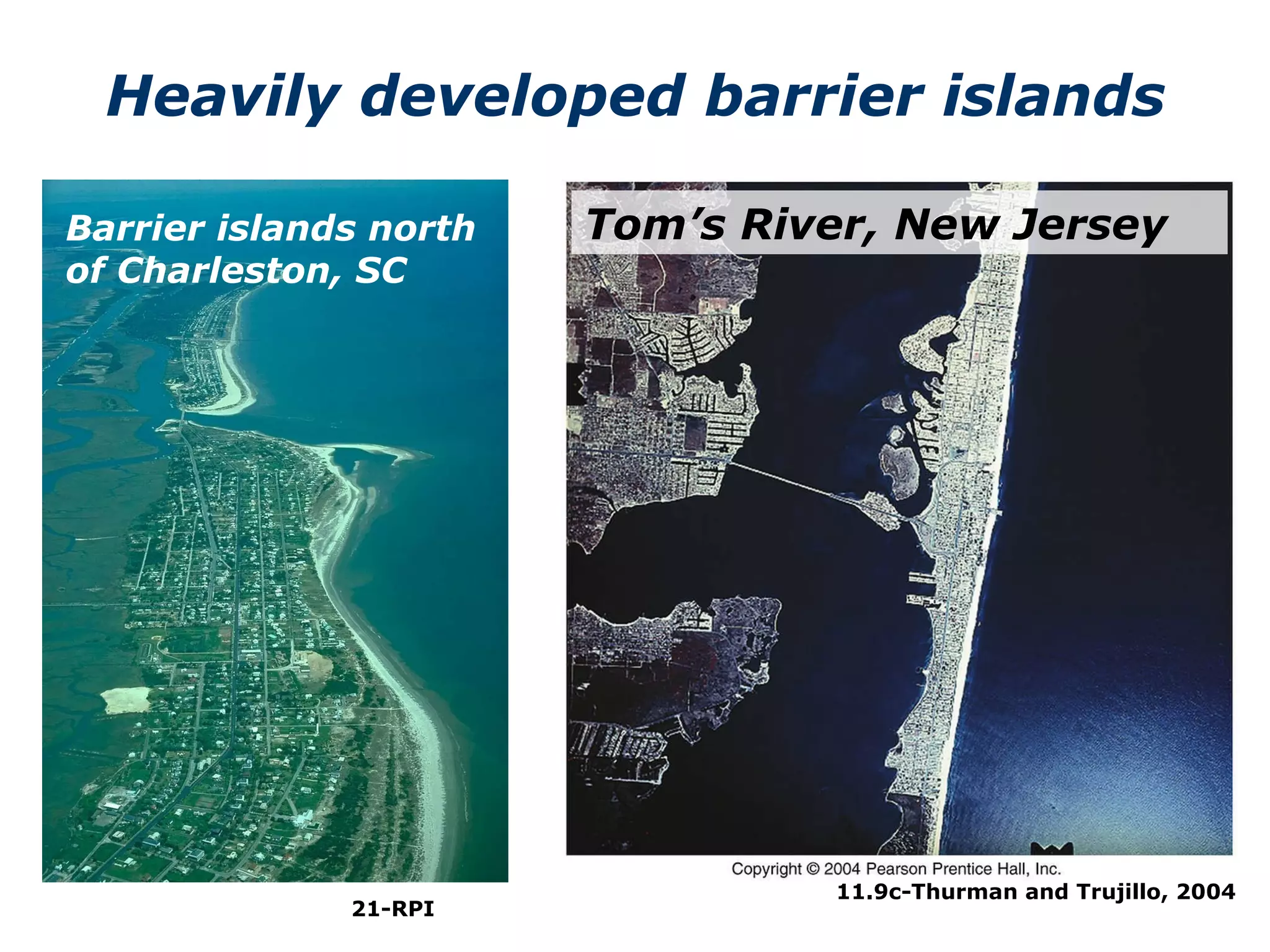

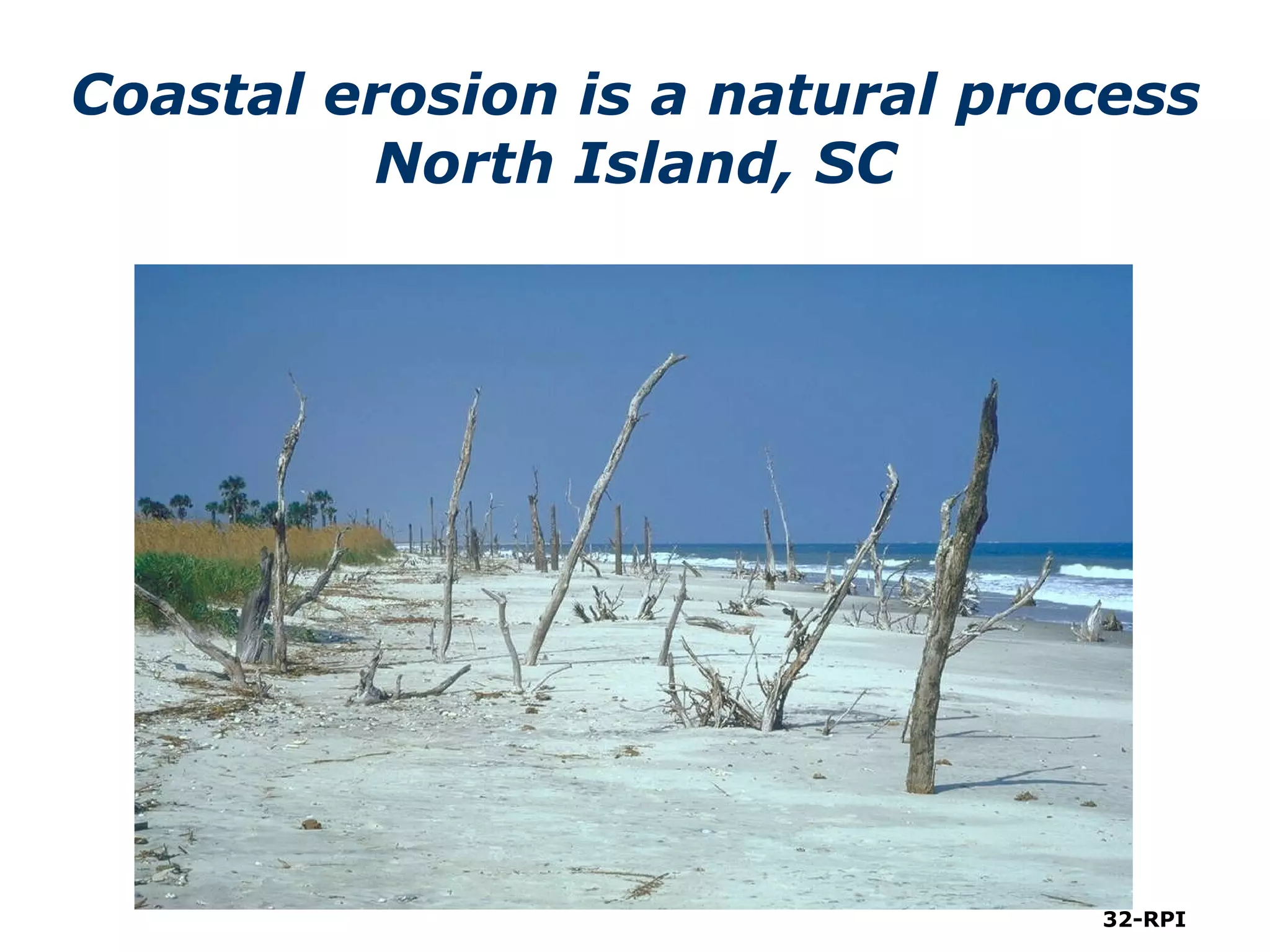

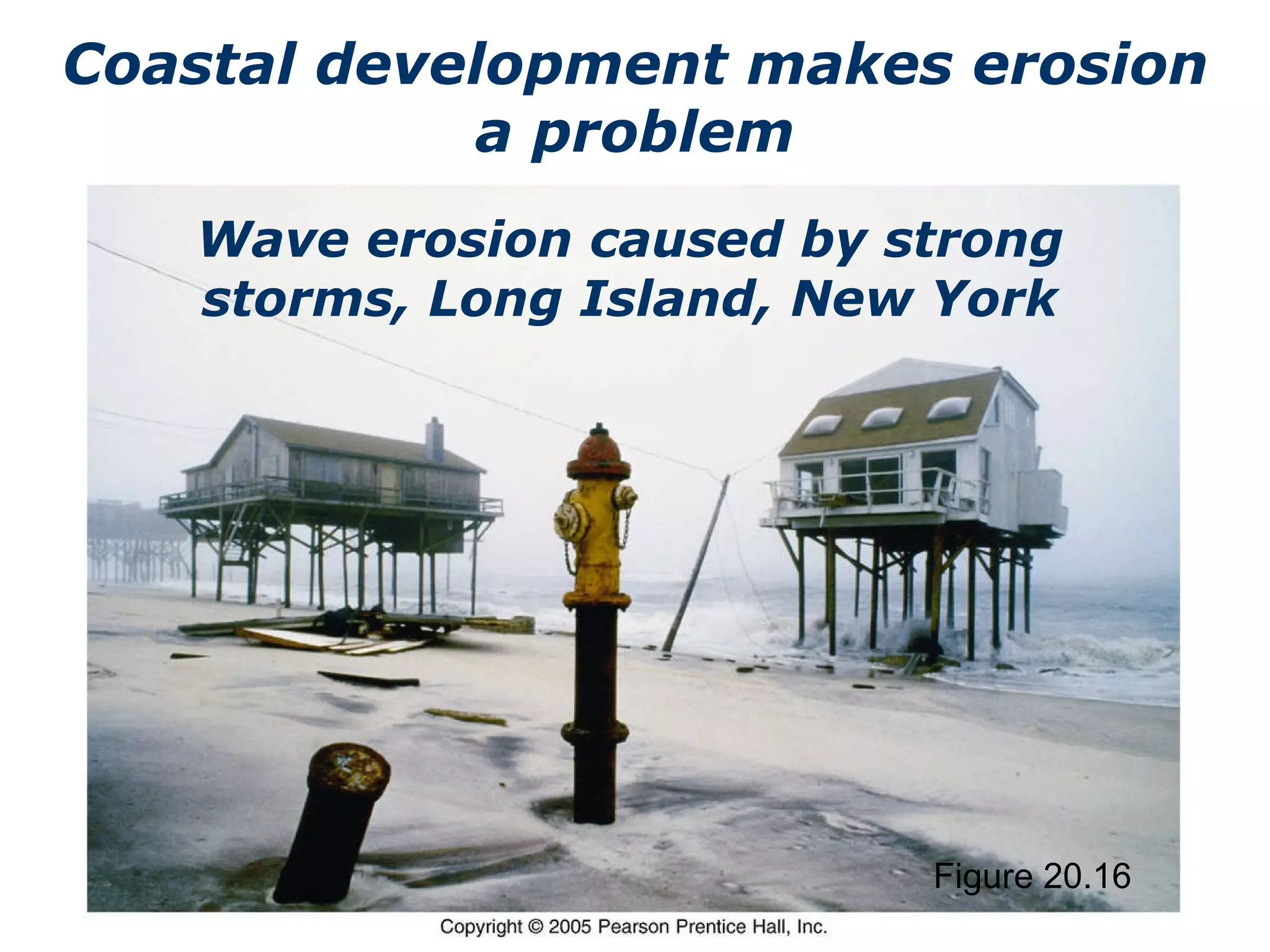

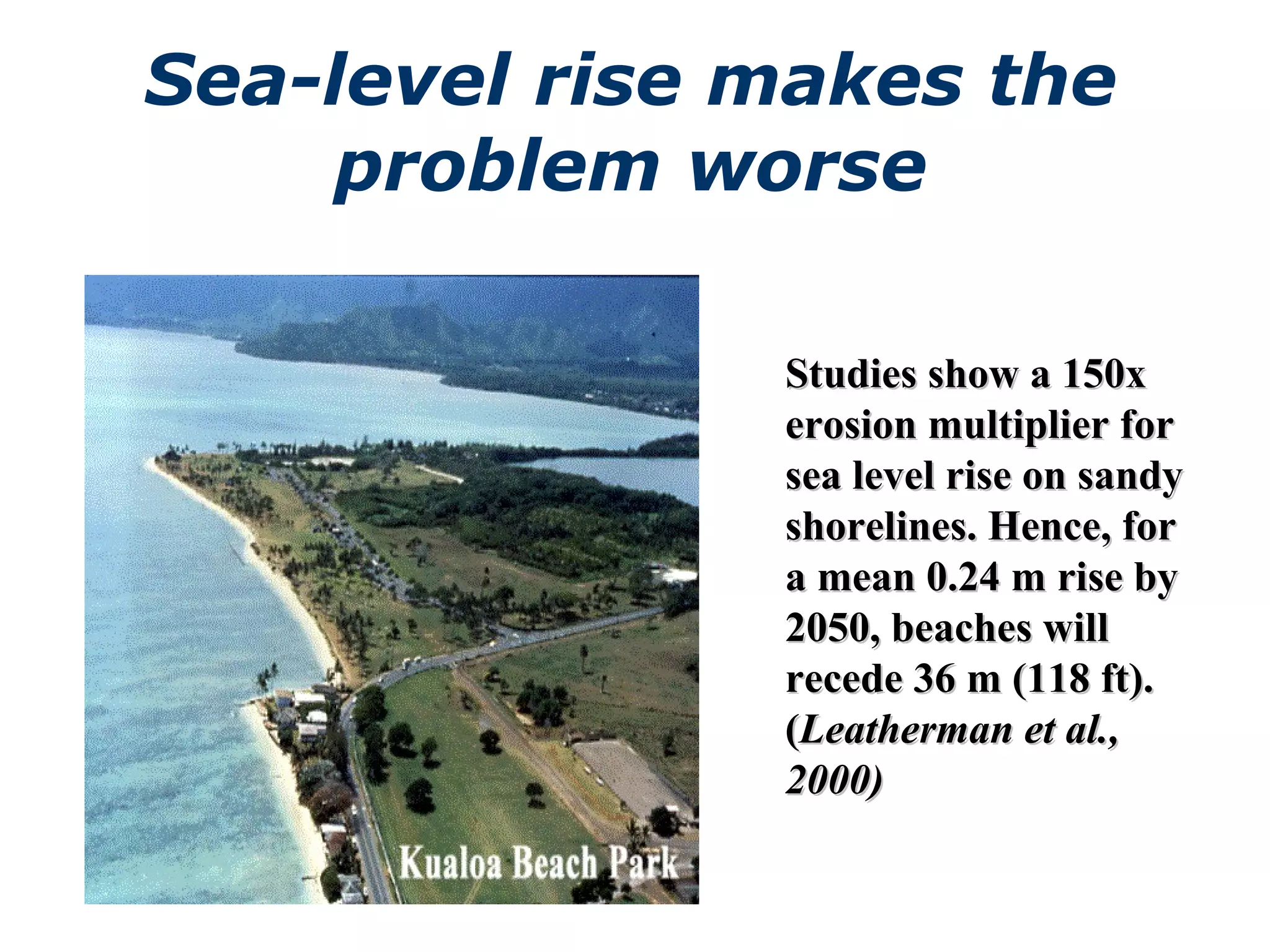

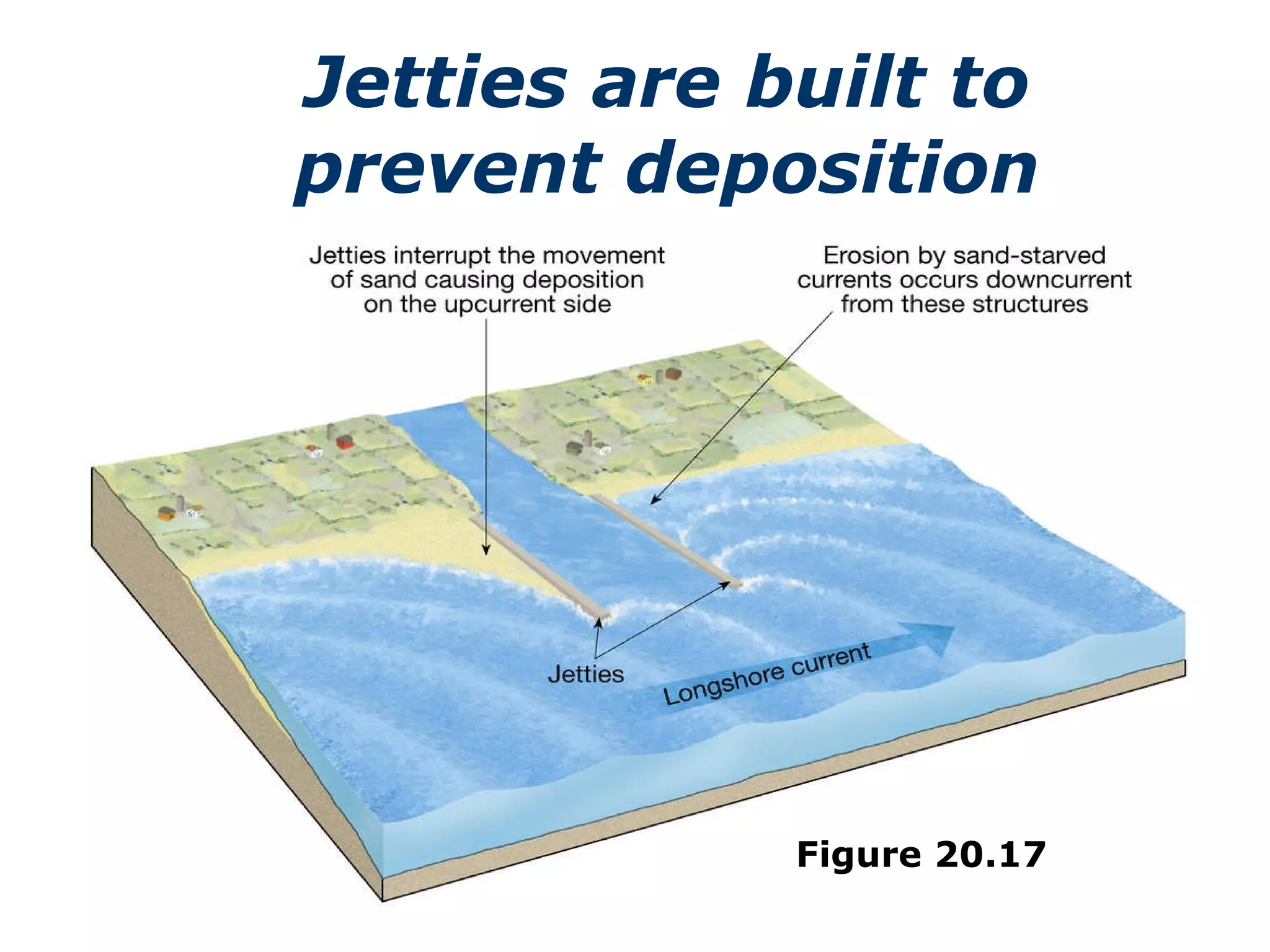

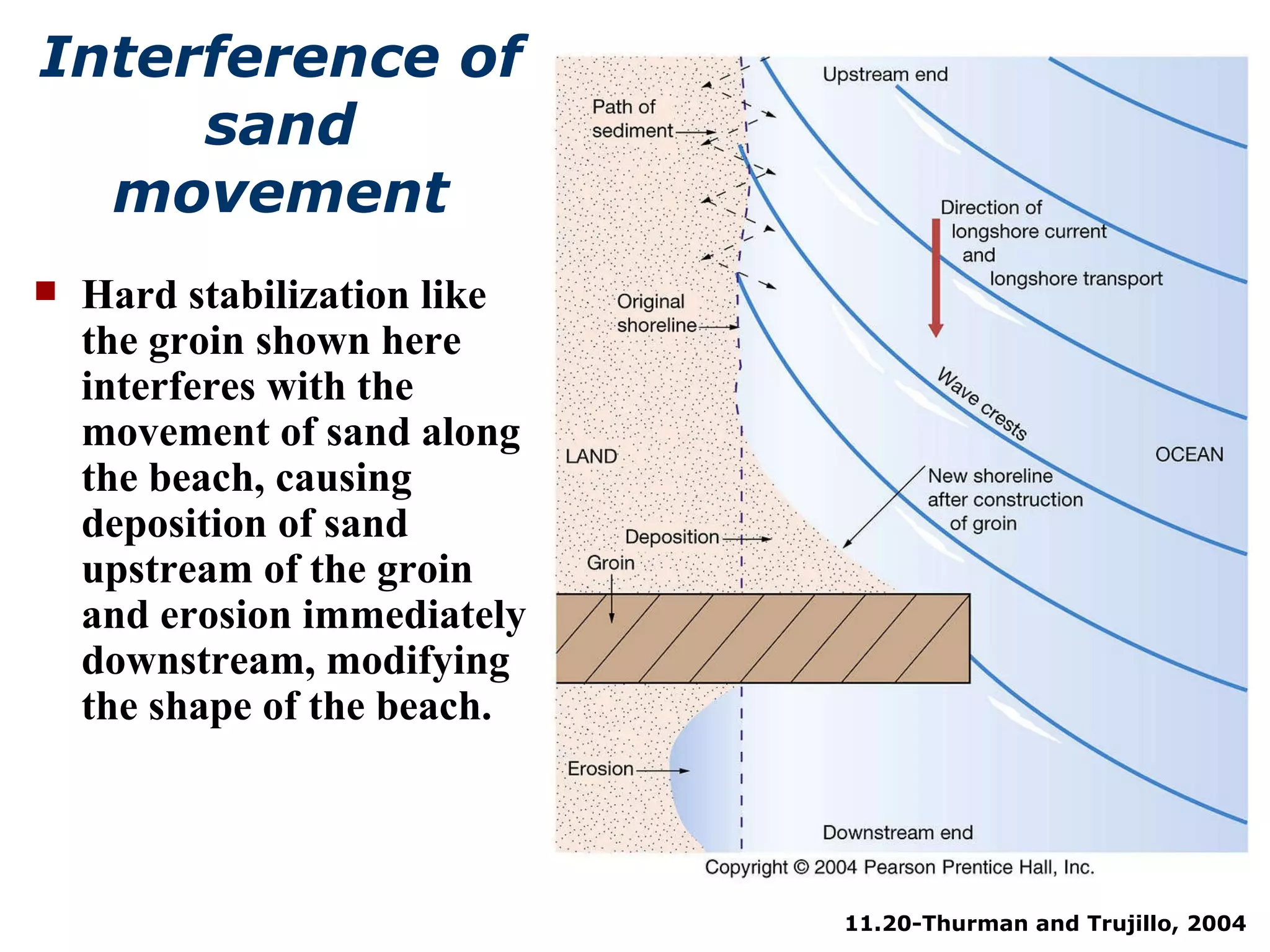

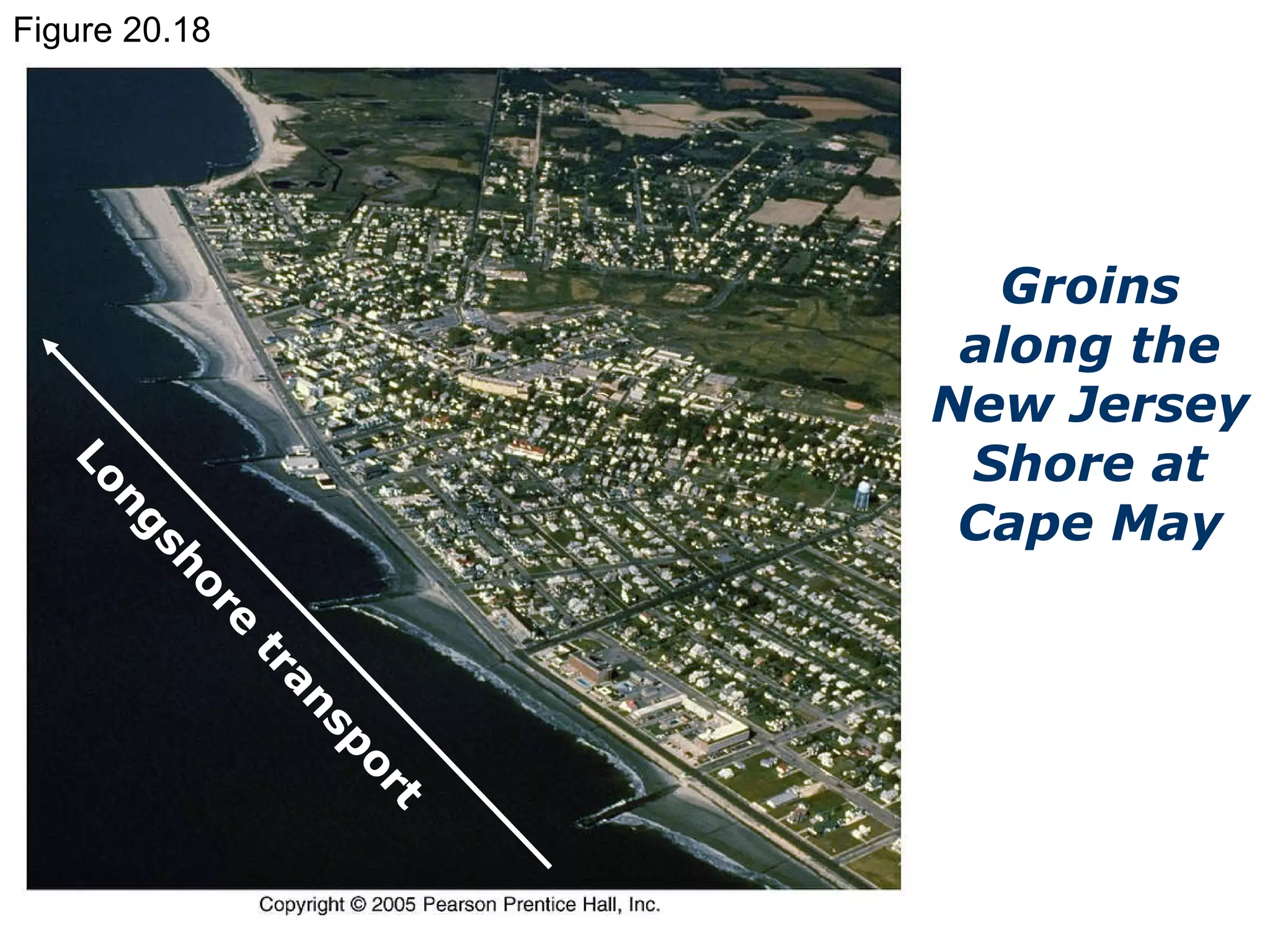

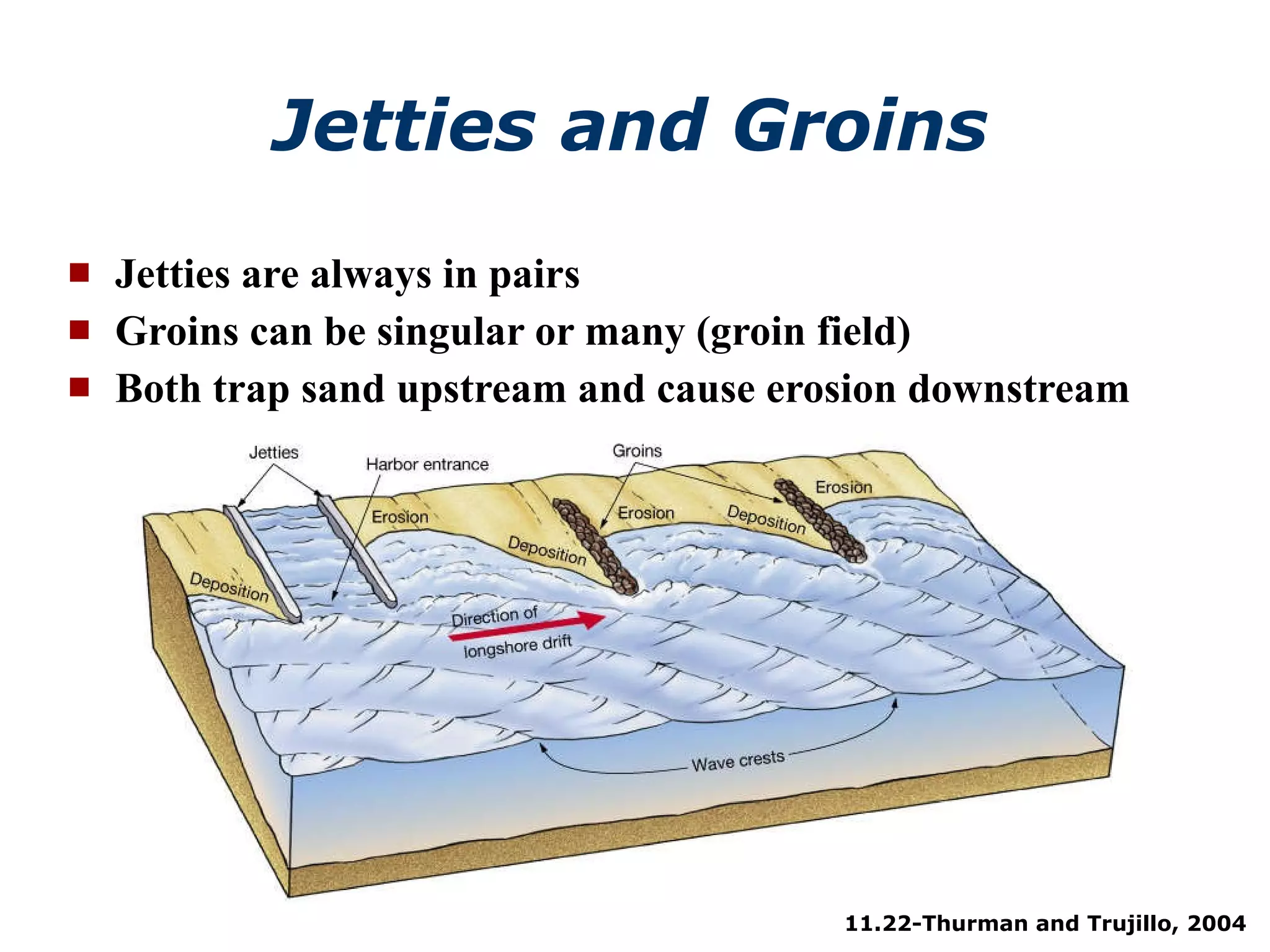

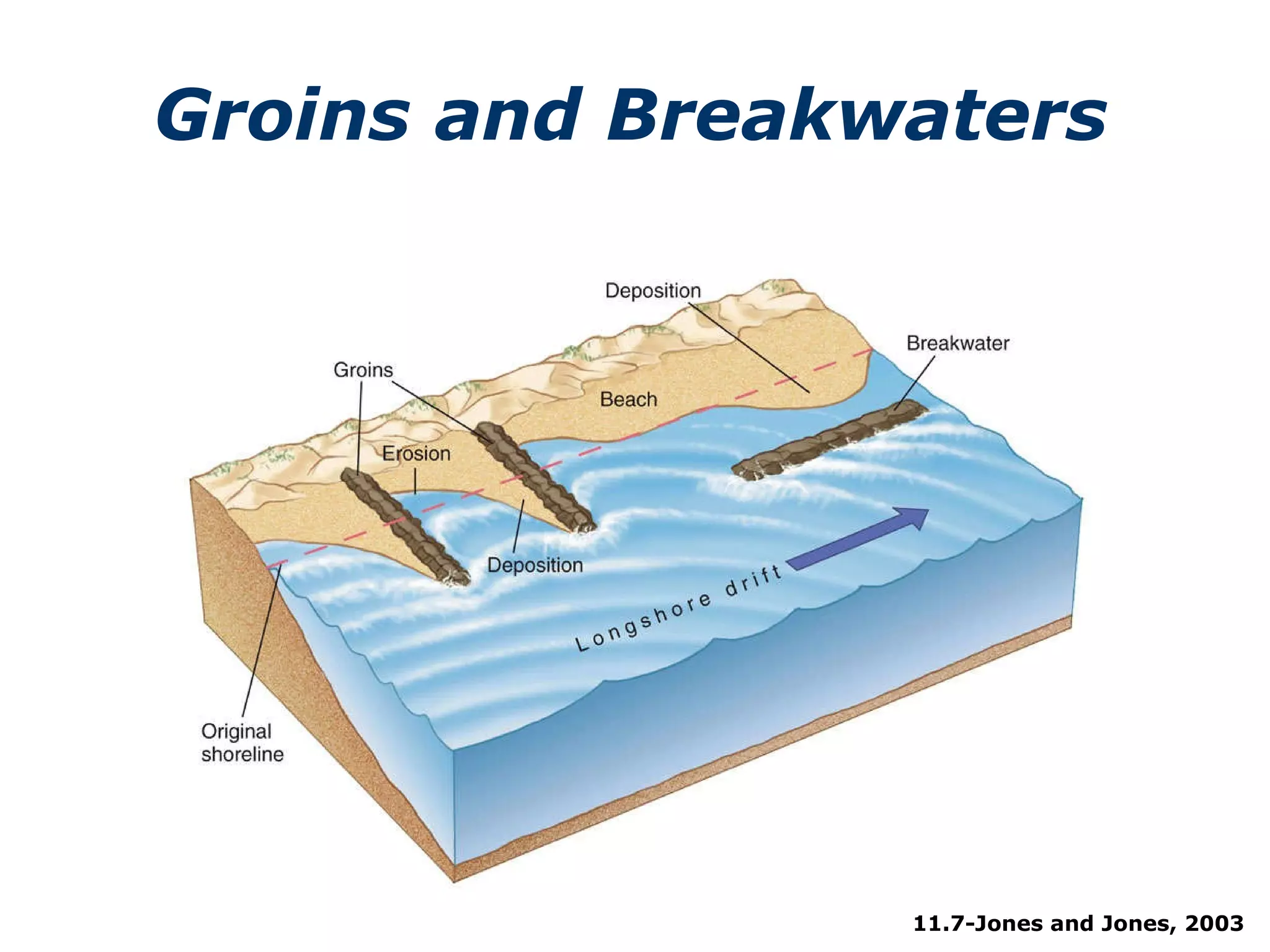

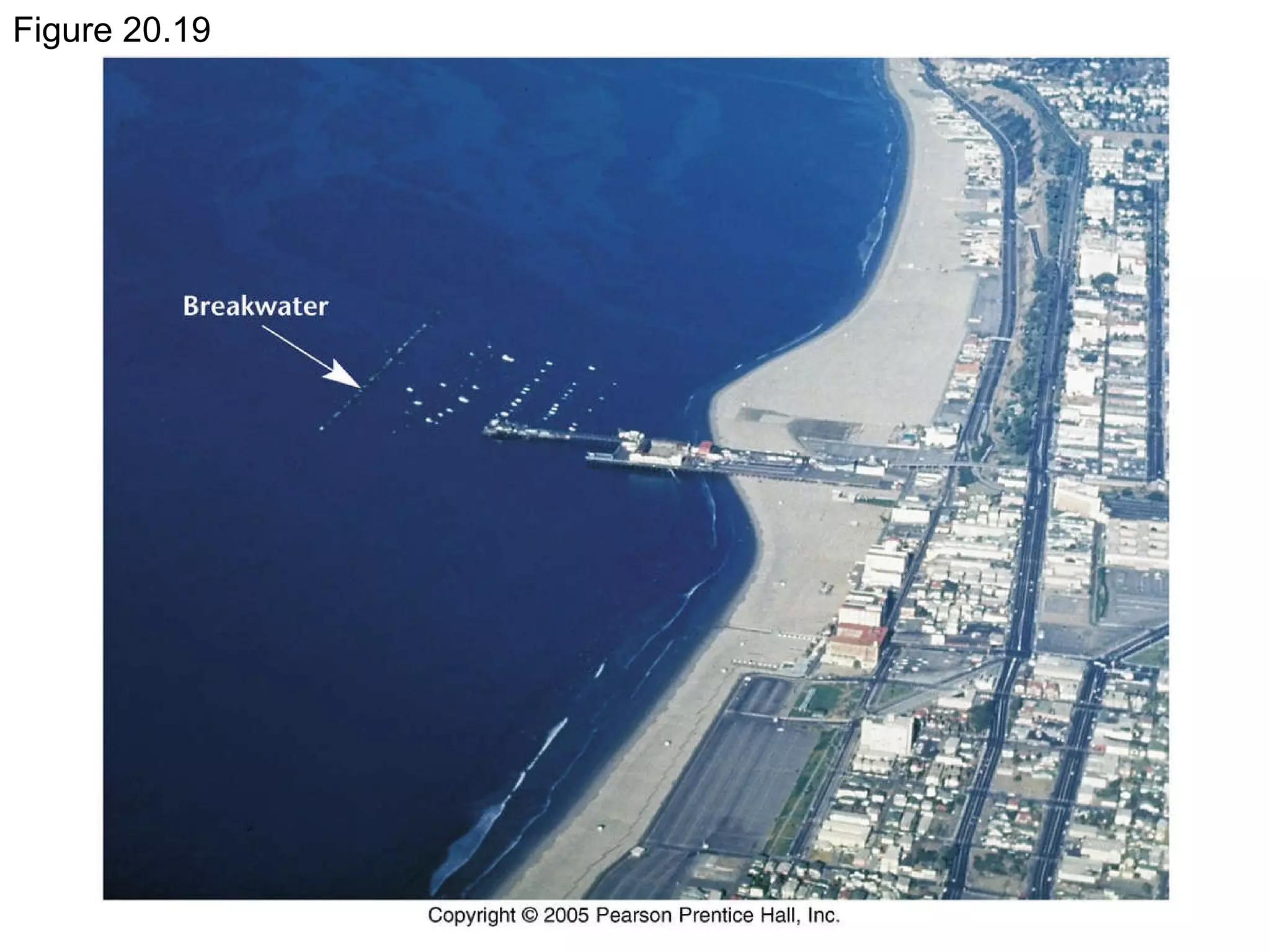

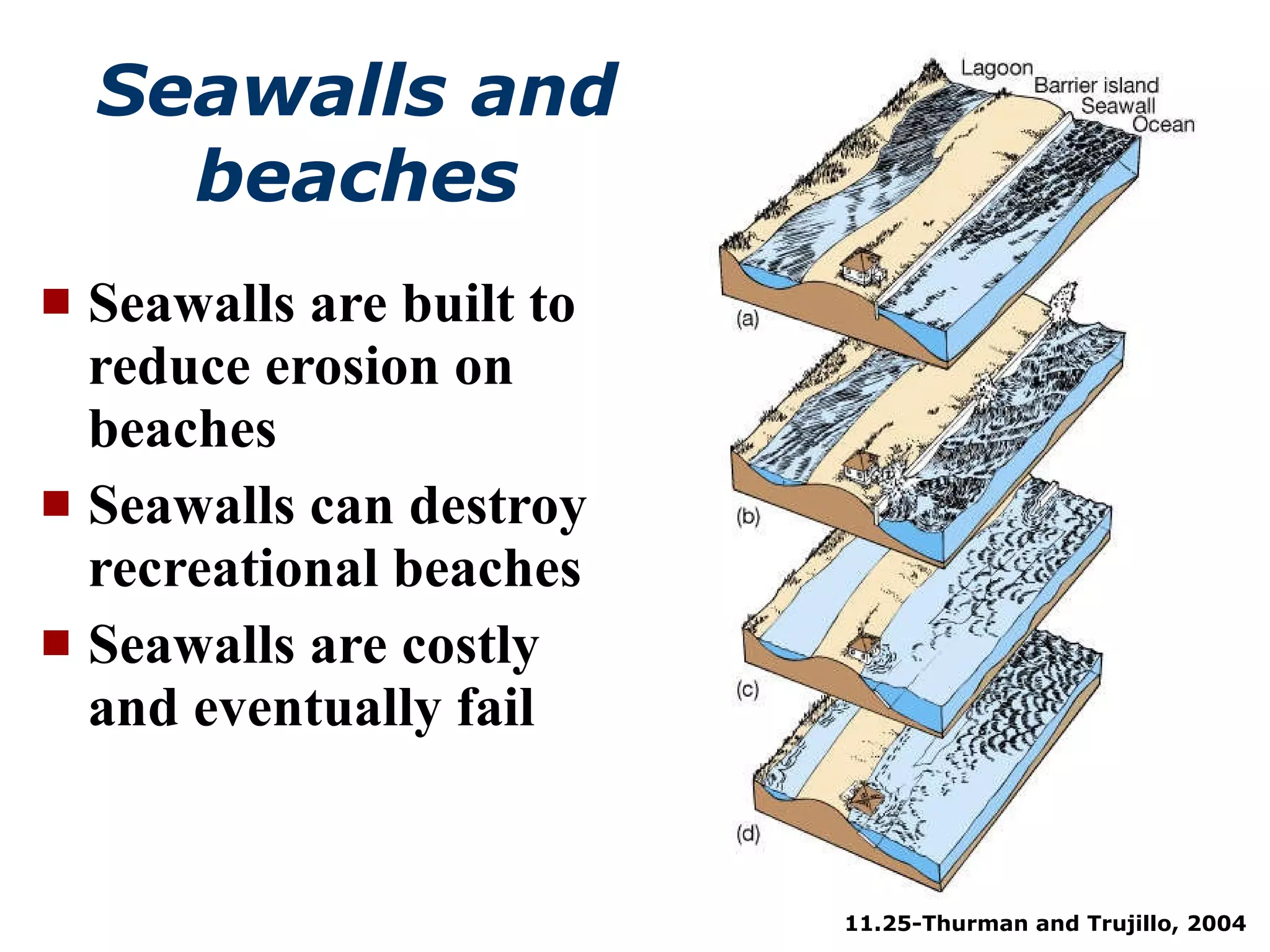

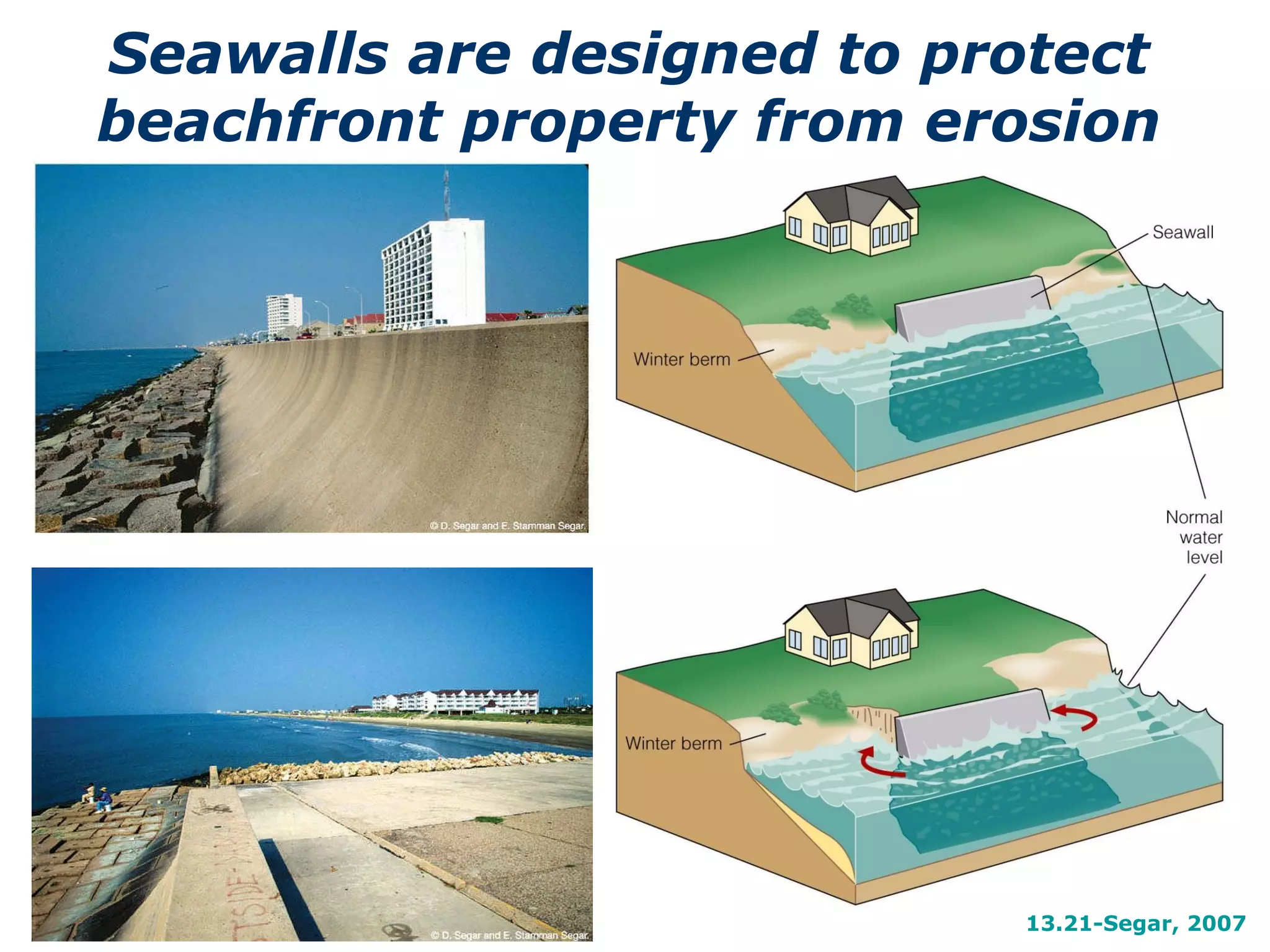

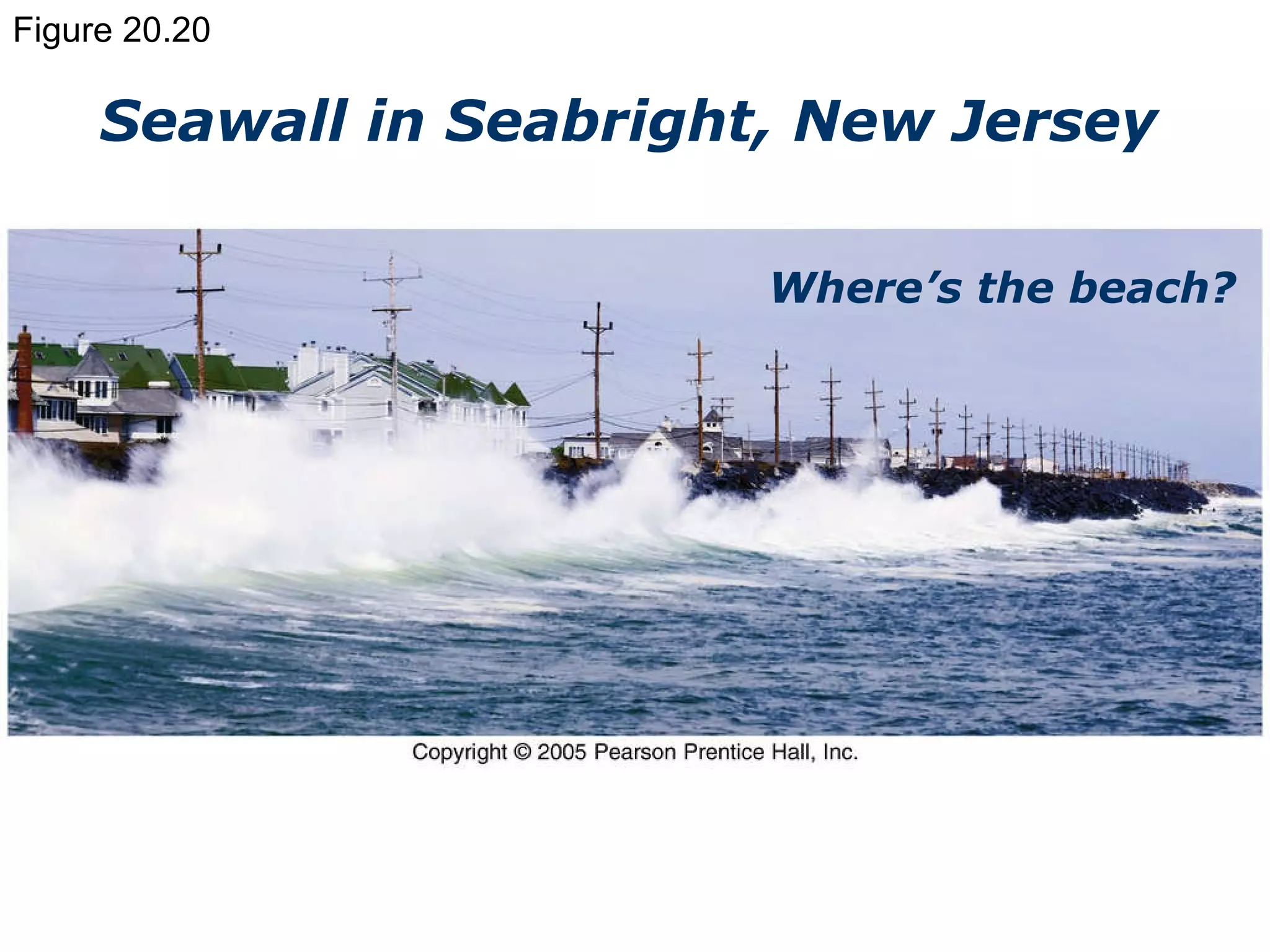

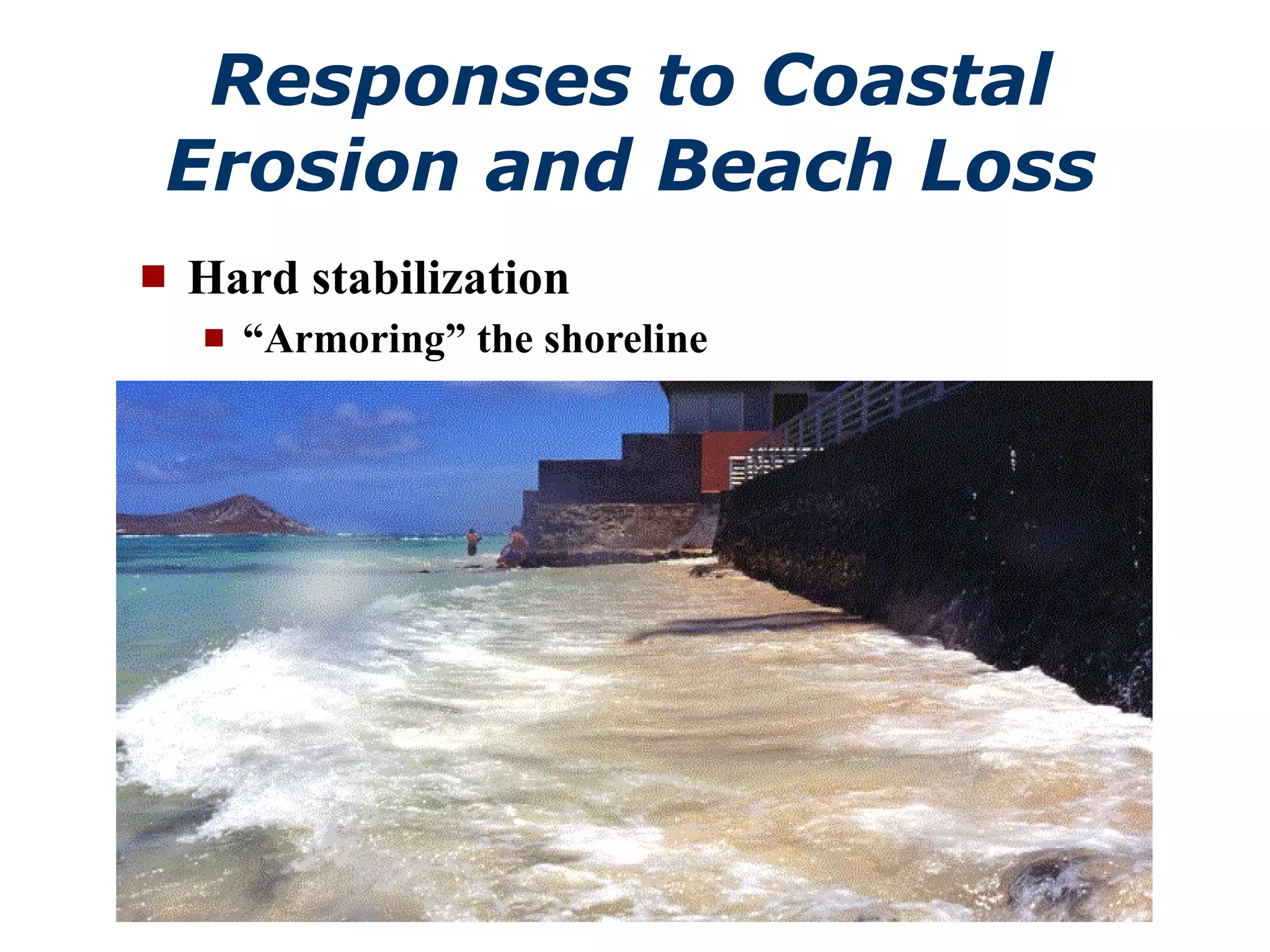

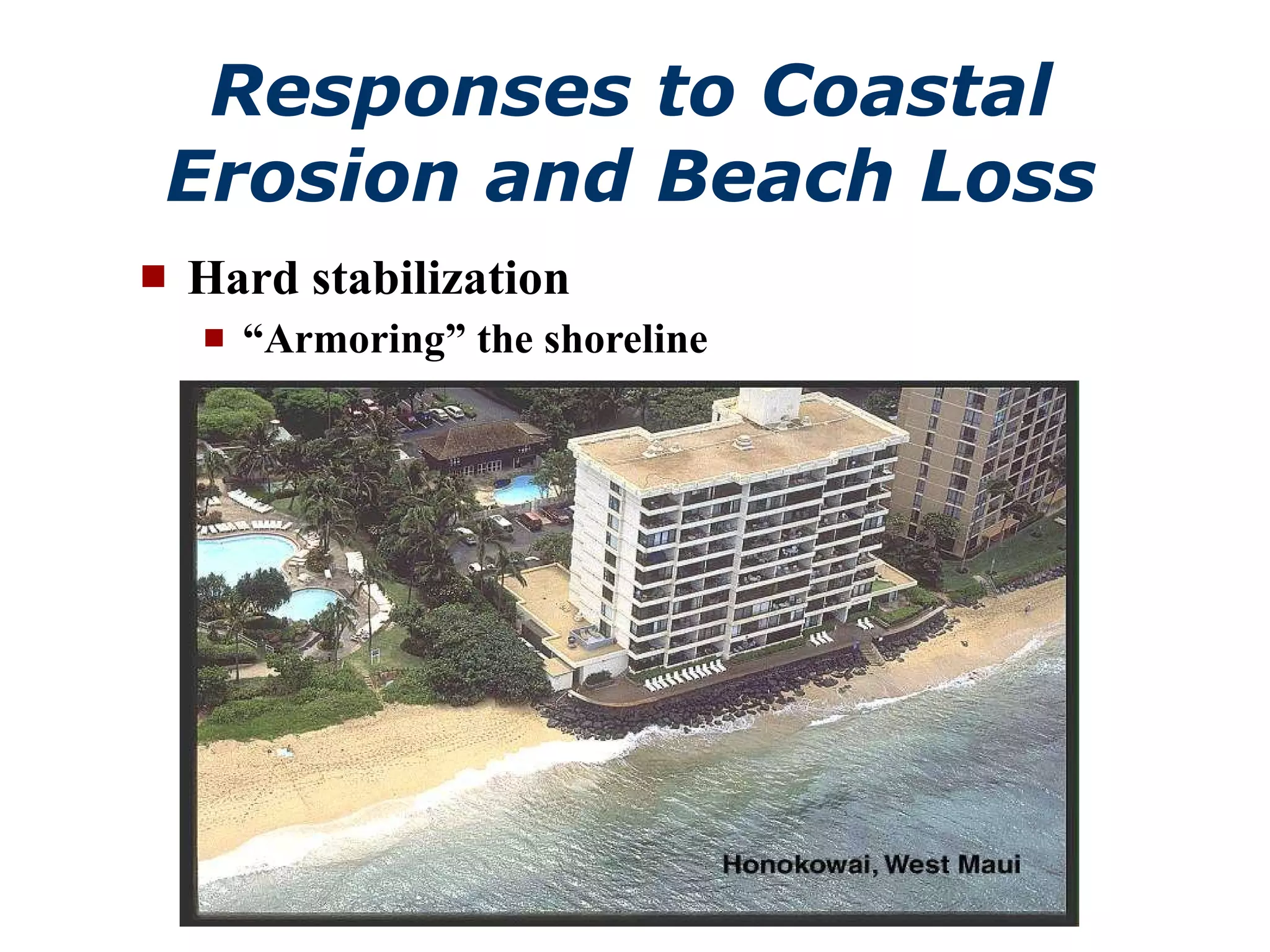

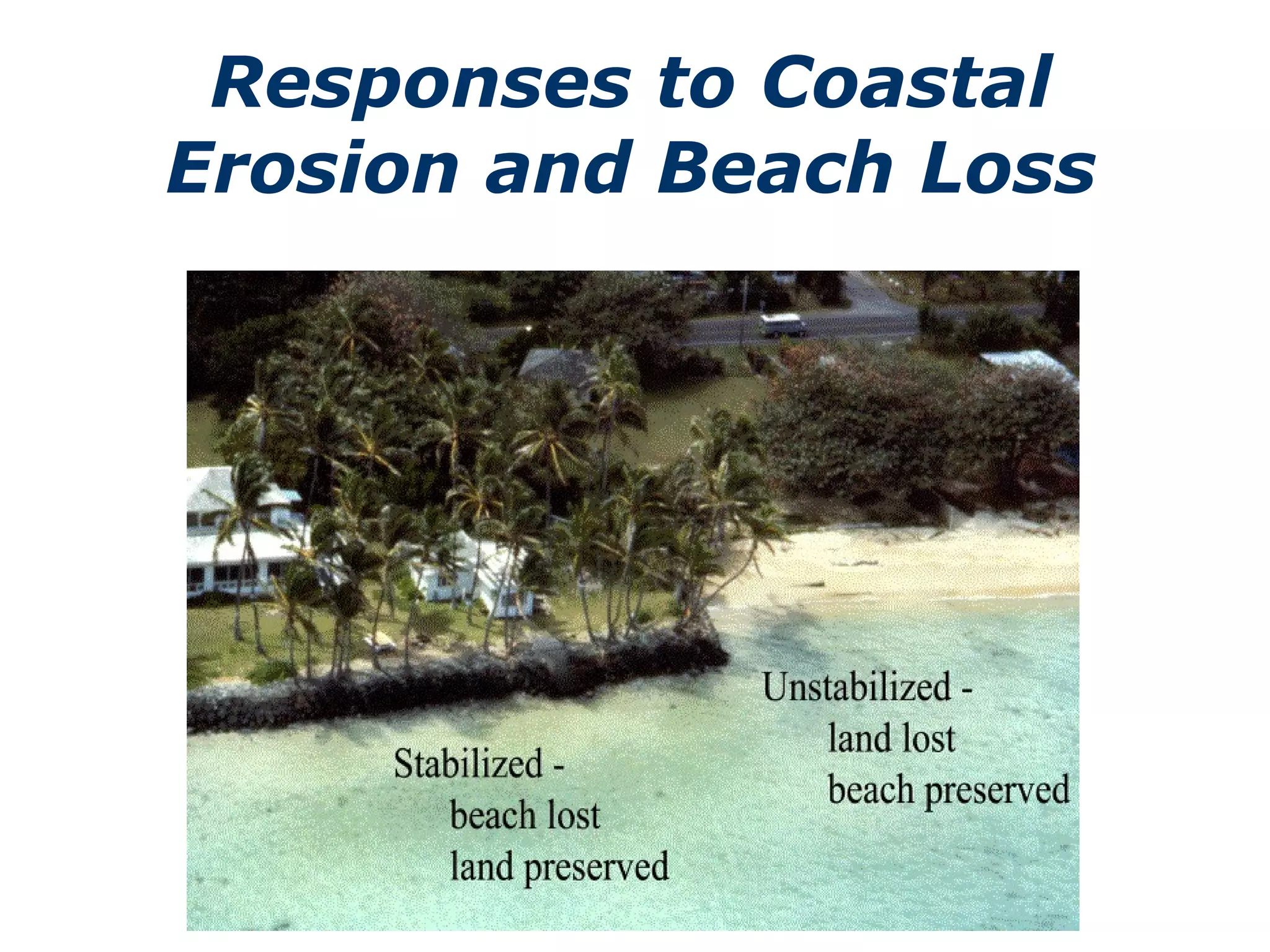

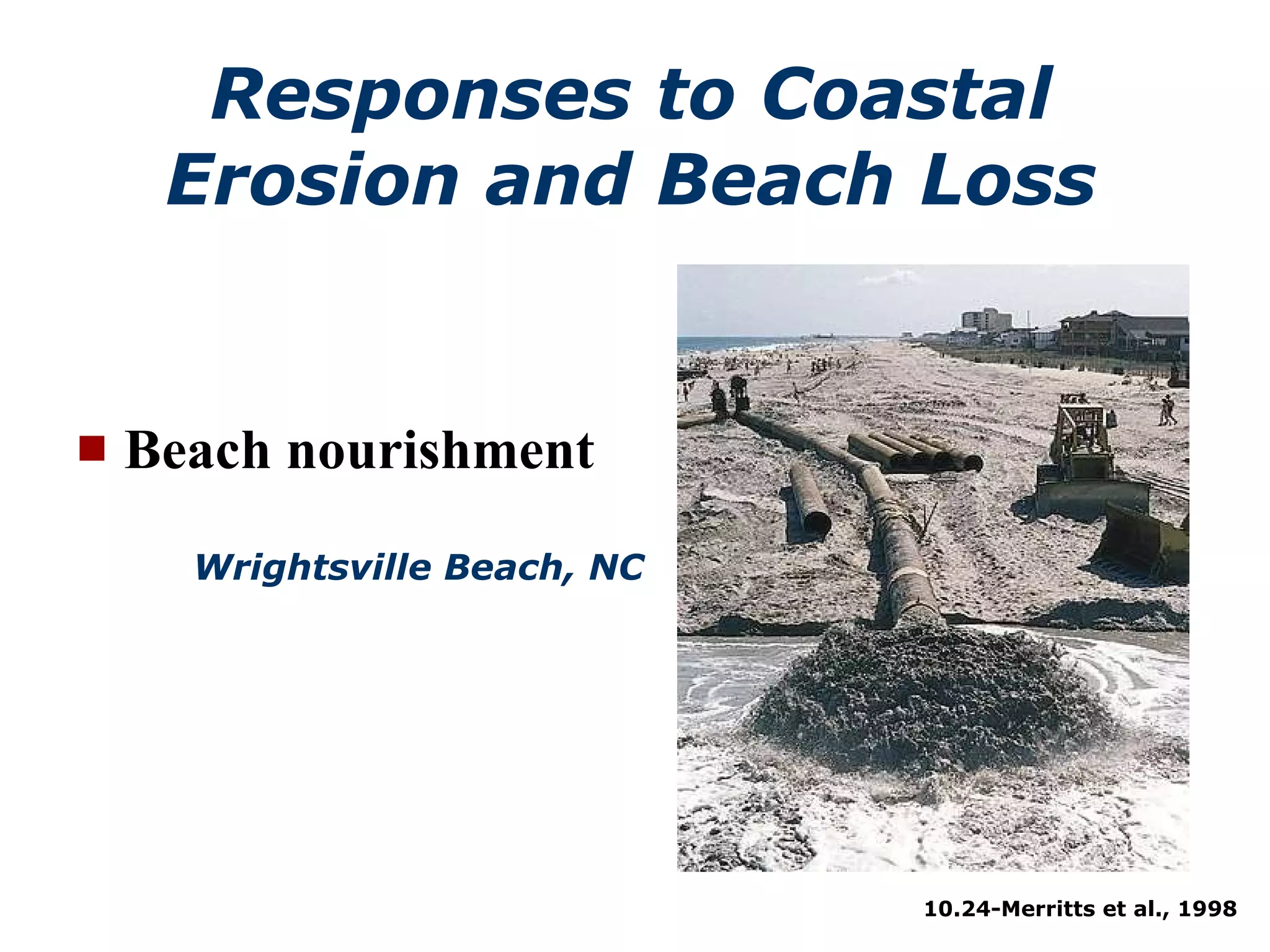

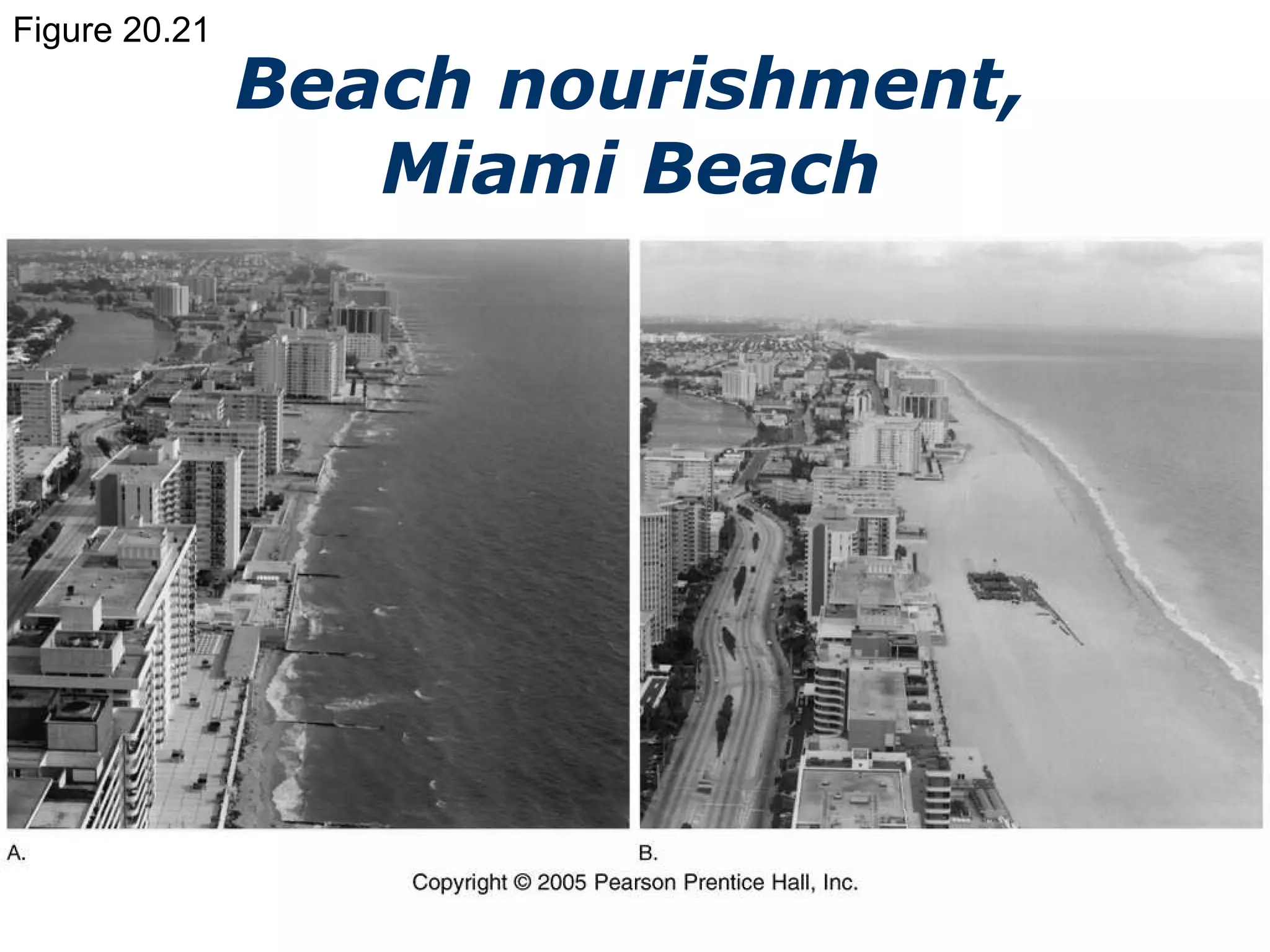

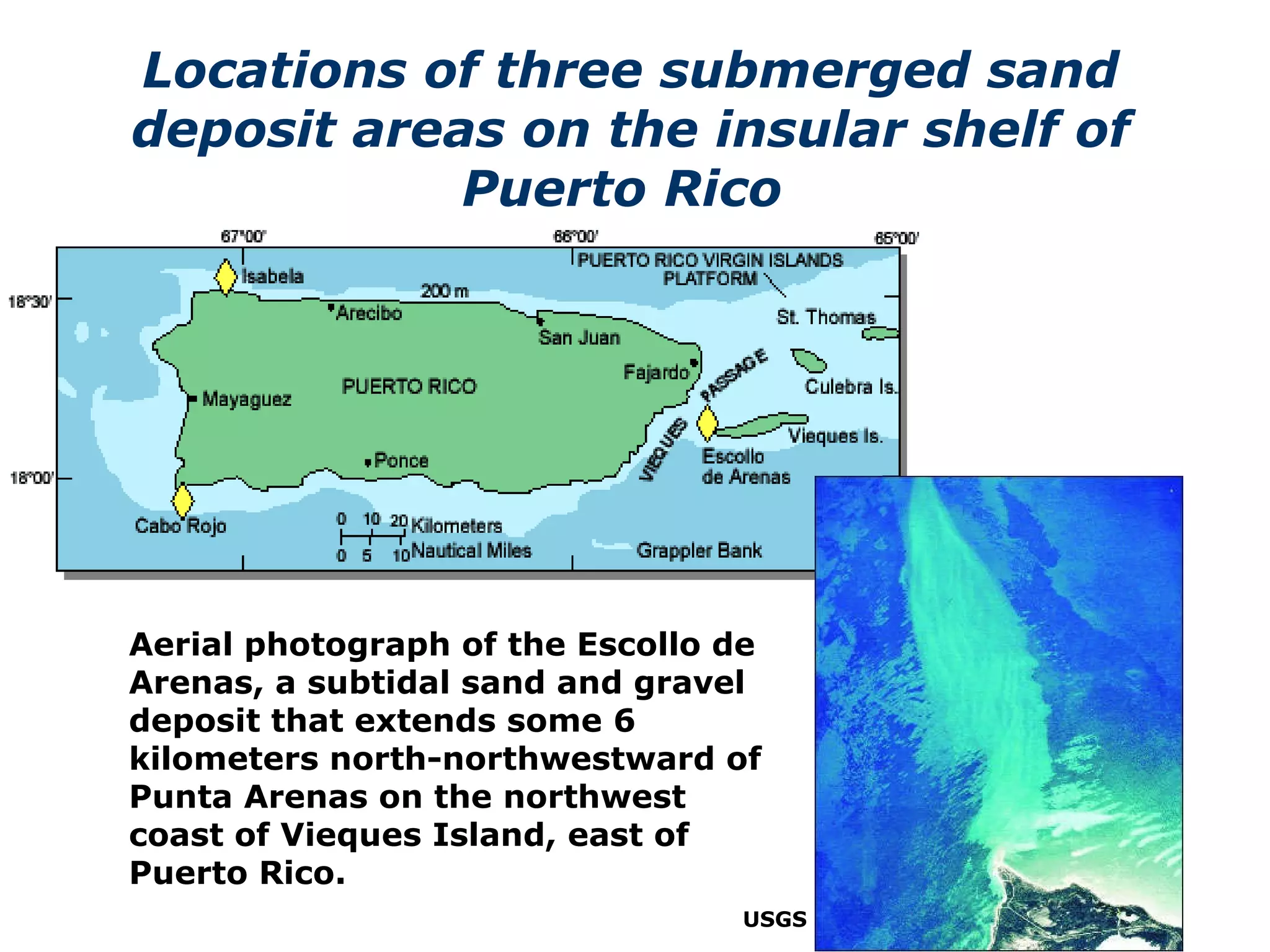

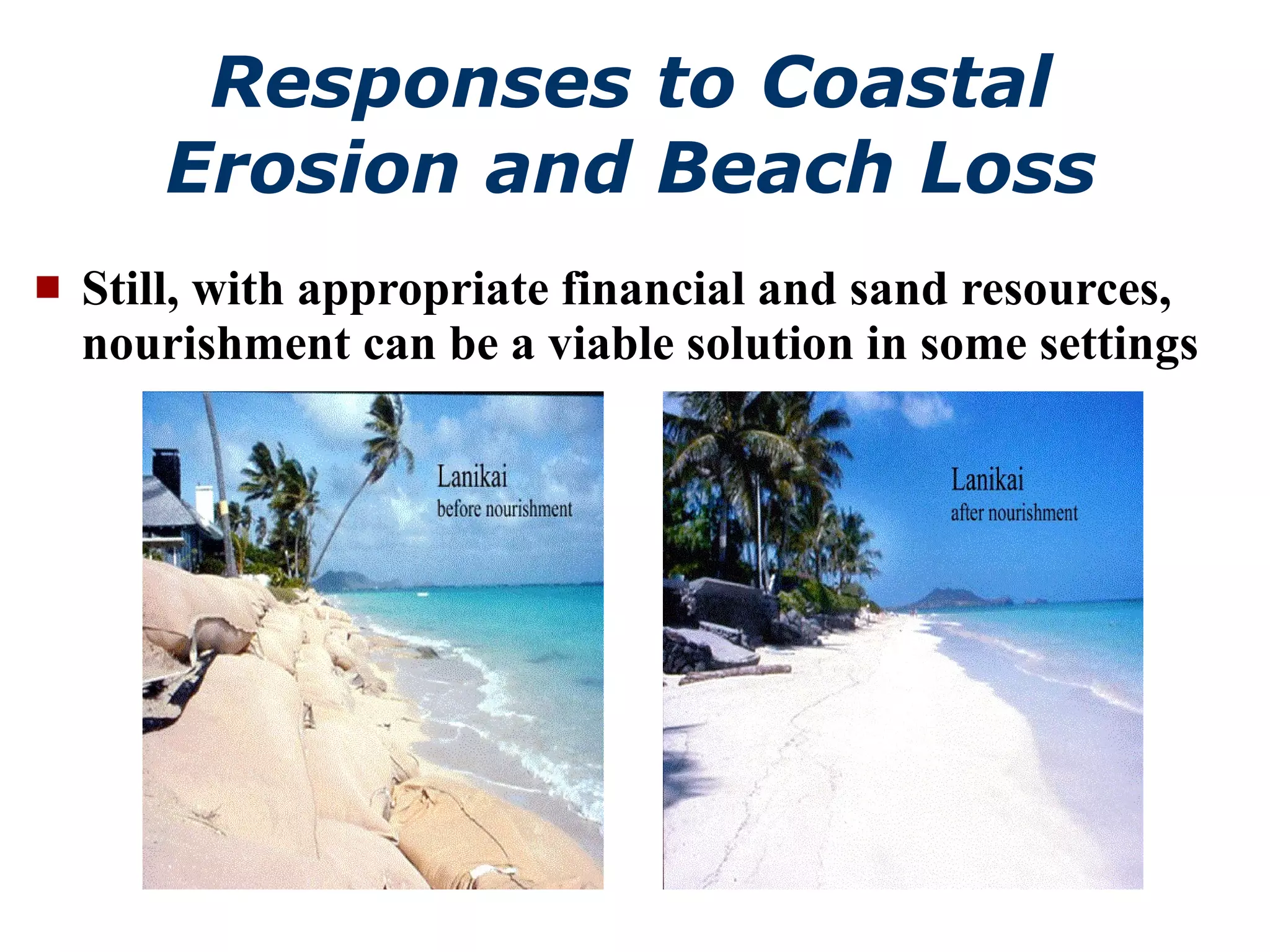

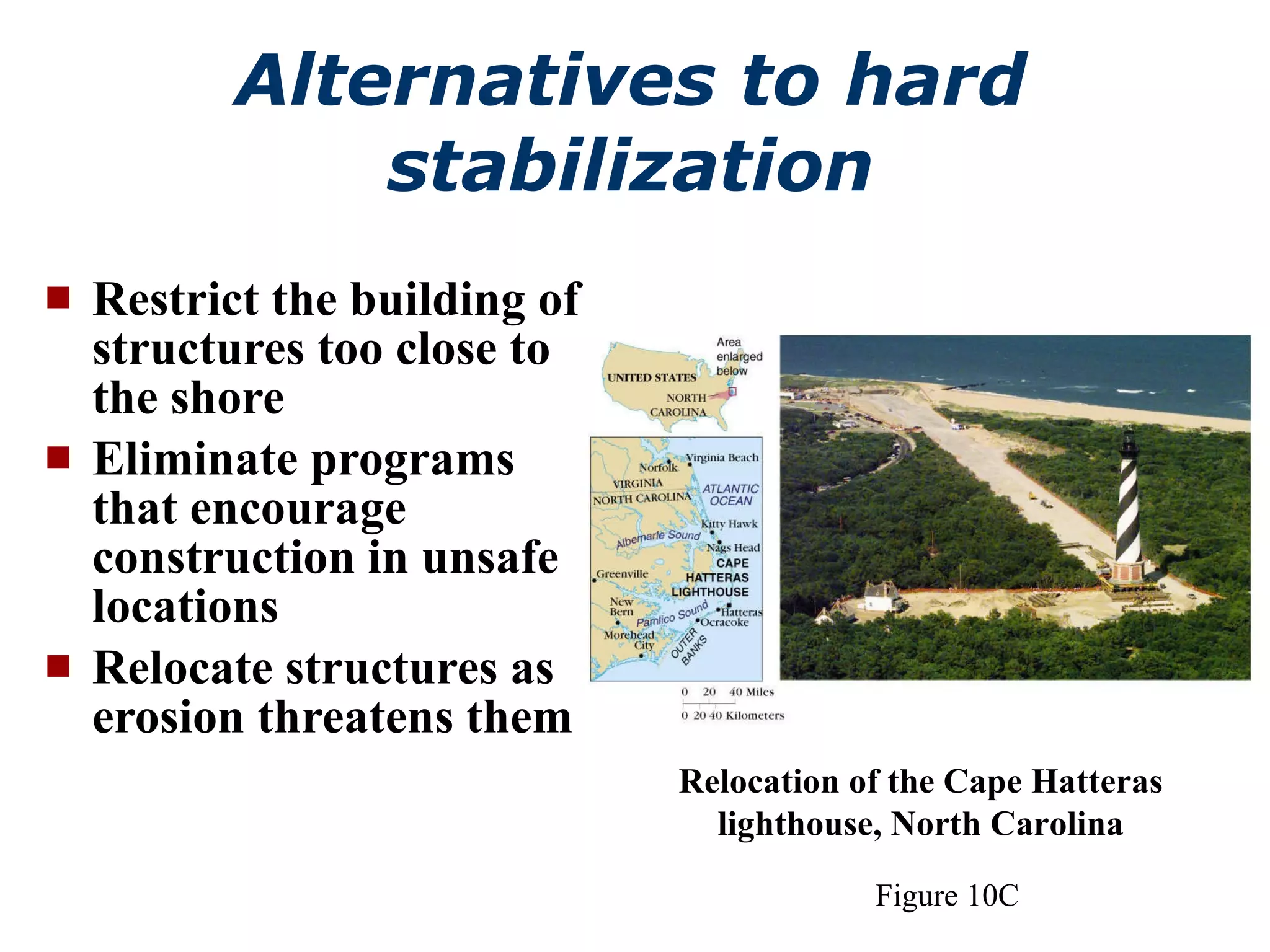

Coastal systems can be divided into erosional shorelines and depositional shorelines based on dominant long-term processes. Erosional shorelines are dominated by erosive forces and typically have high-relief rocky coasts, while depositional shorelines are dominated by depositional processes and include environments like deltas, barrier islands, and reef coasts. Coasts experience various erosive and depositional processes from waves, such as refraction, longshore drift, and swash/backwash, which shape the shoreline over time. Stabilizing eroding coasts involves hard structures, beach nourishment, or relocation, but these approaches have limitations and tradeoffs.