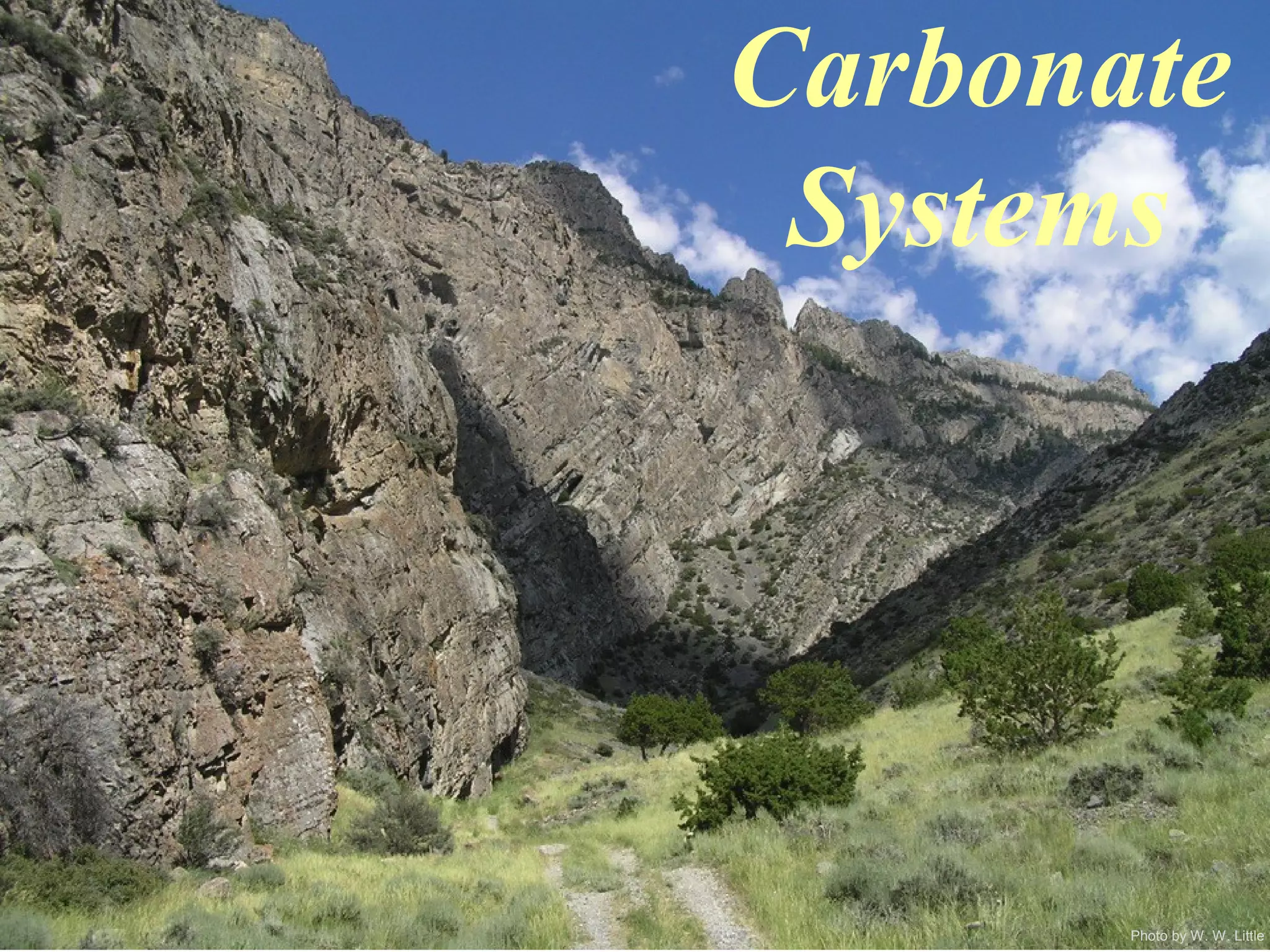

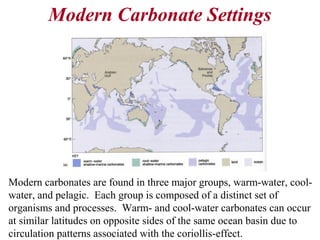

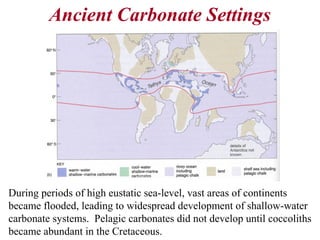

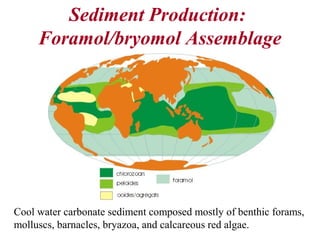

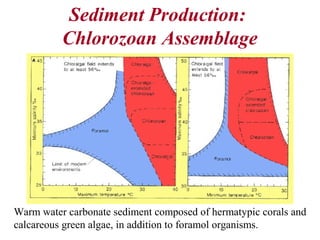

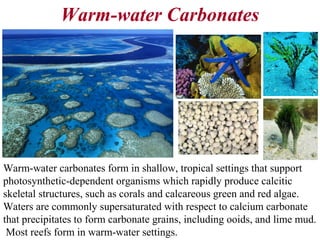

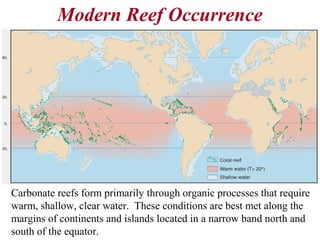

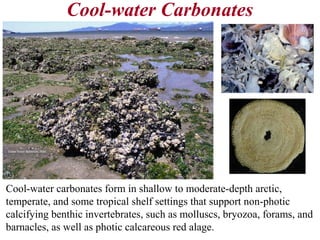

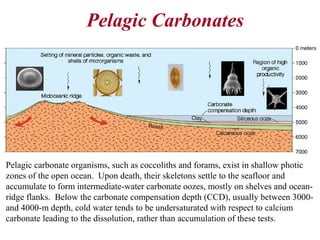

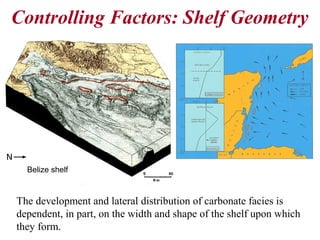

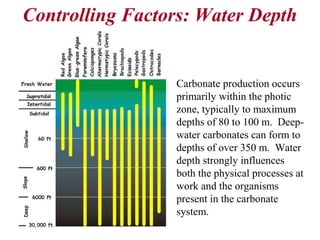

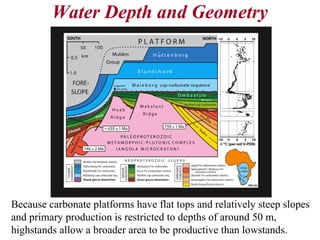

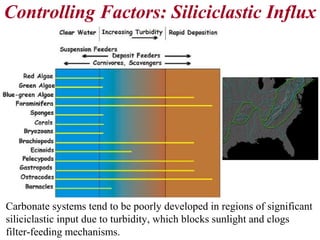

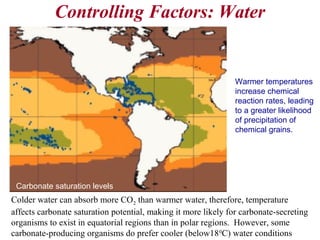

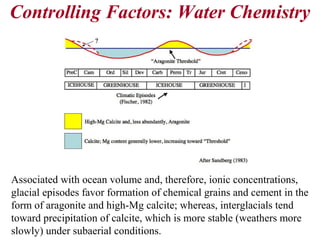

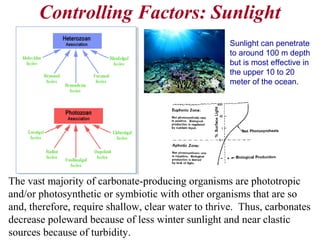

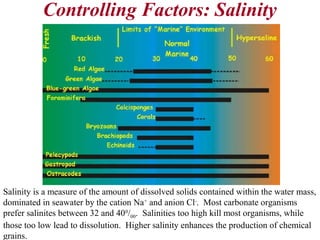

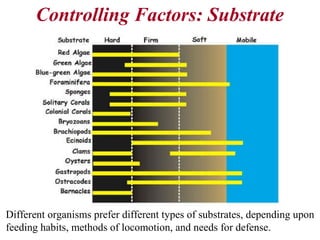

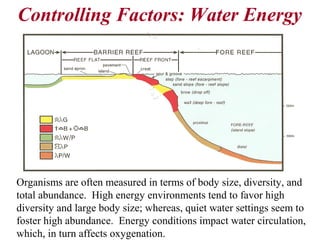

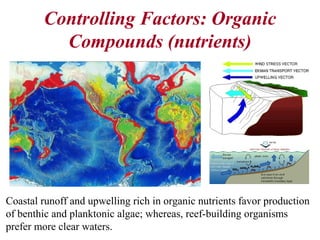

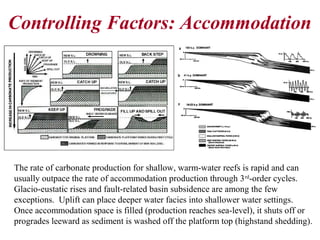

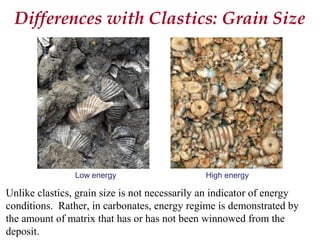

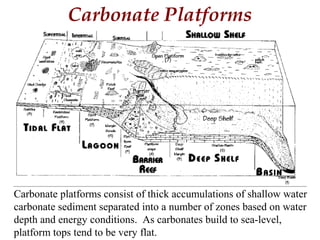

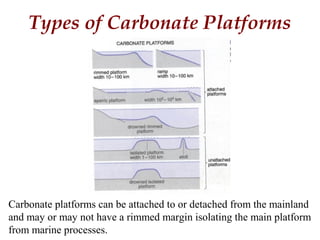

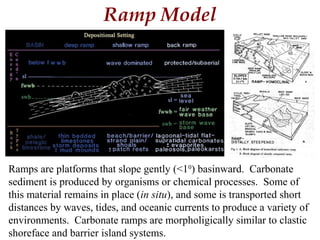

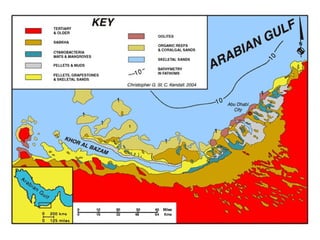

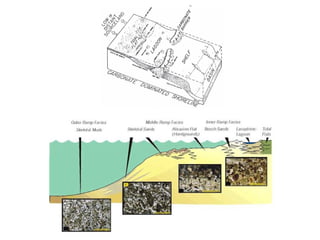

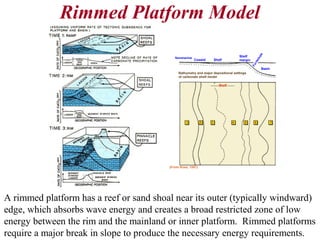

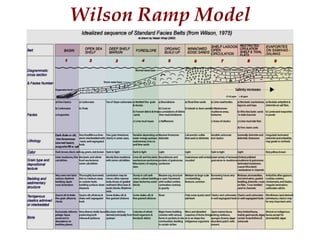

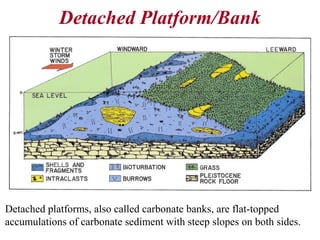

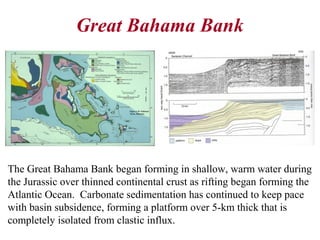

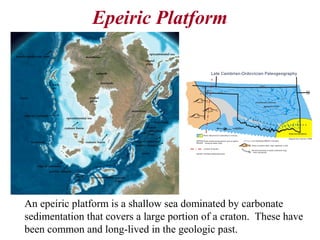

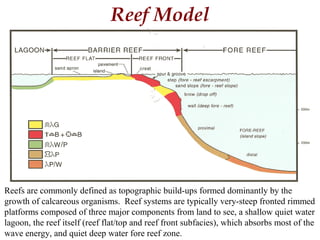

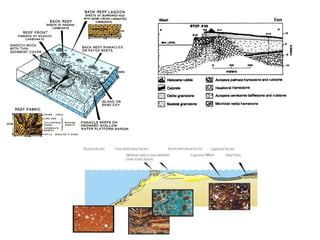

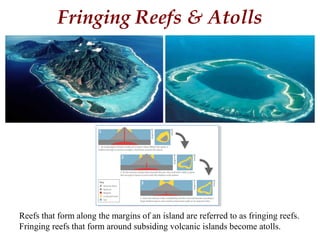

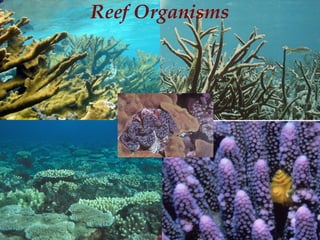

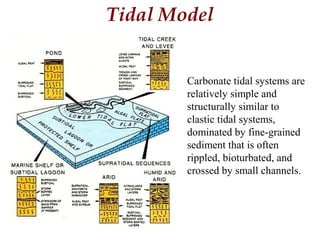

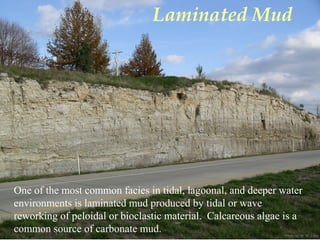

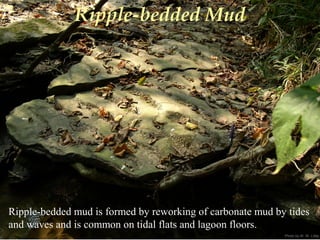

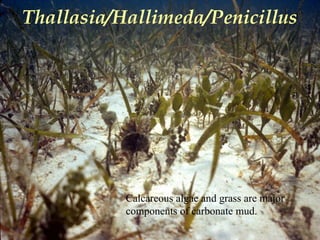

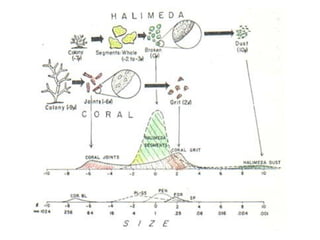

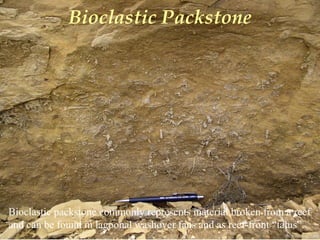

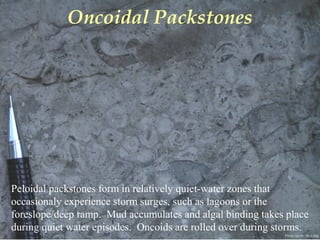

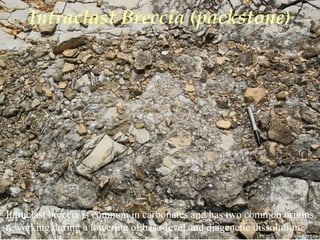

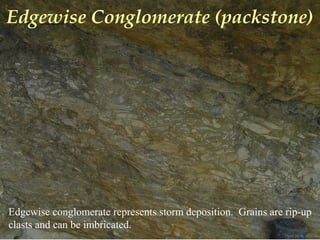

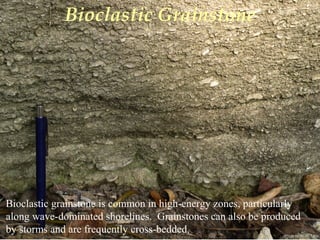

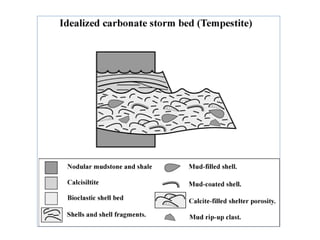

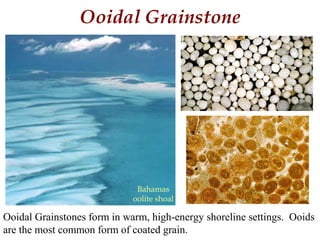

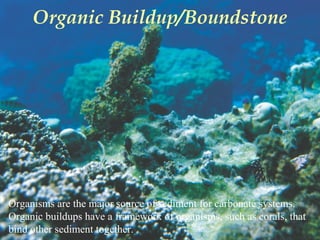

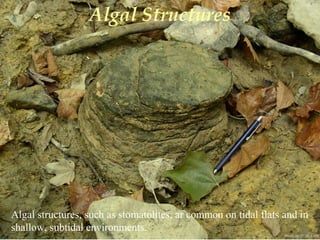

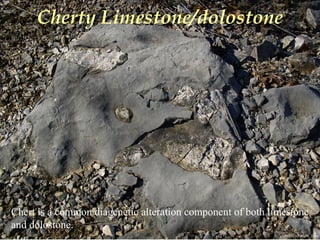

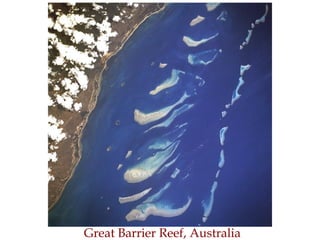

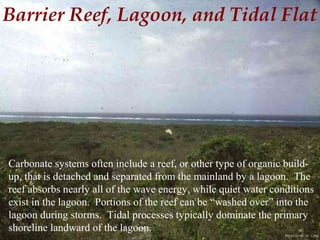

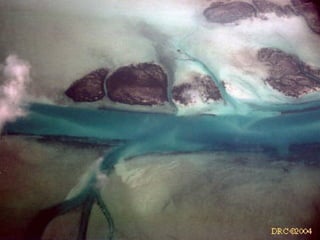

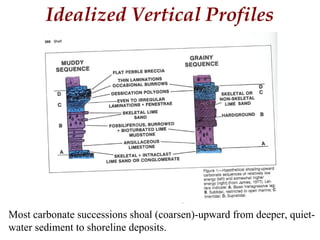

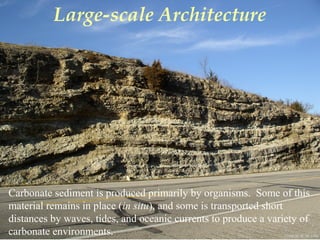

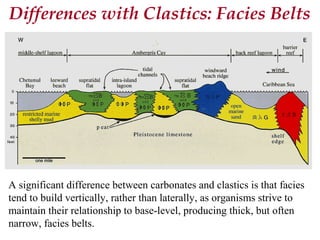

This document provides information on carbonate systems, including their formation processes, modern and ancient settings, controlling factors, and sedimentary facies. Carbonate sediment is formed through biological processes controlled by factors like temperature, salinity, and clastic sediment influx. Modern carbonates are found in warm-water, cool-water, and pelagic settings. Ancient carbonates developed on flooded continental shelves during high sea levels. Carbonate platforms, ramps, reefs, and other depositional environments are described.