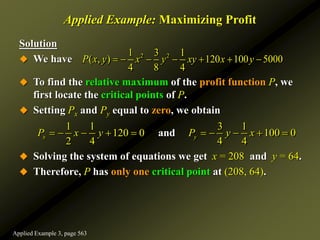

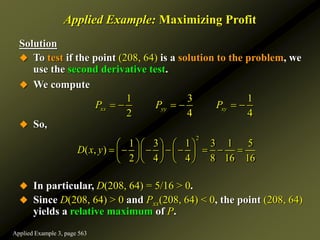

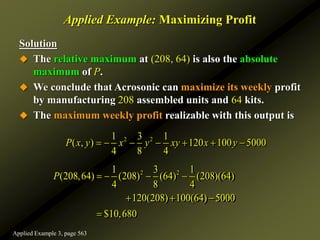

This document discusses several topics in calculus of several variables:

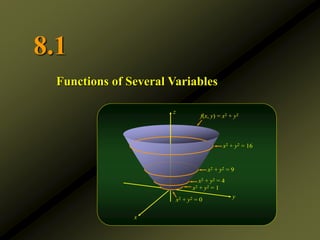

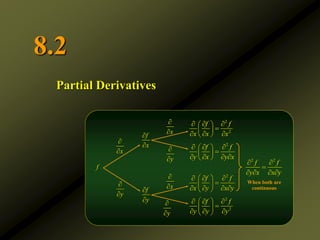

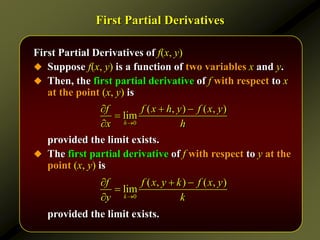

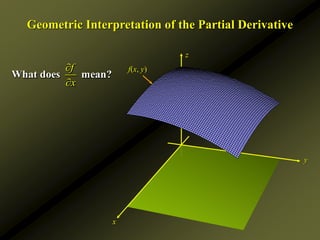

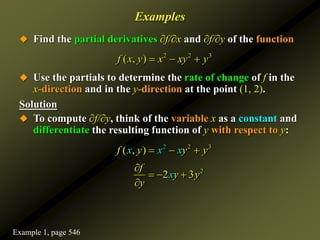

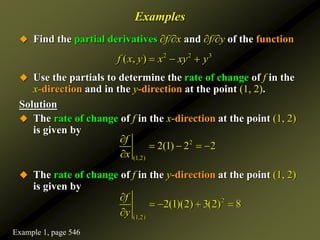

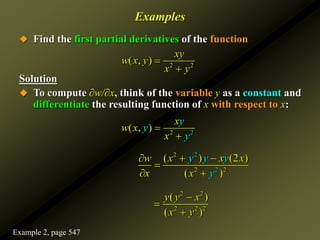

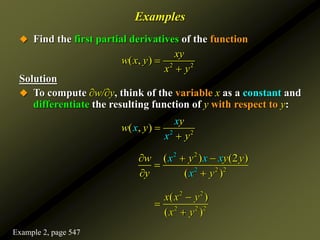

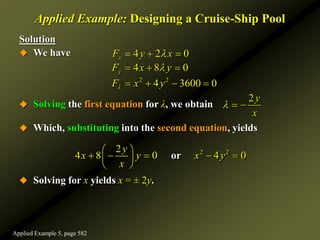

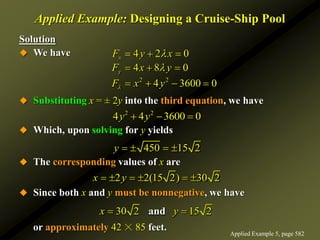

- Functions of several variables and their partial derivatives

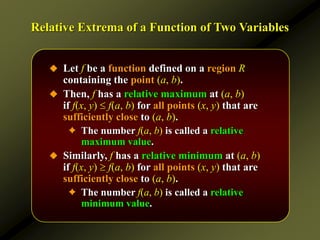

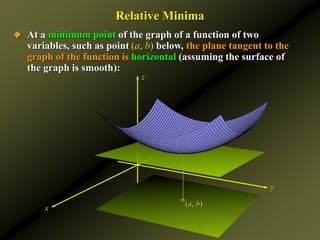

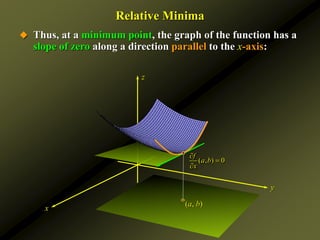

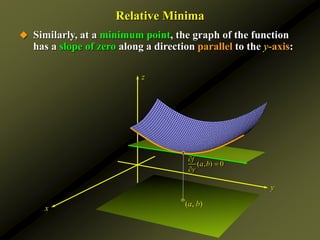

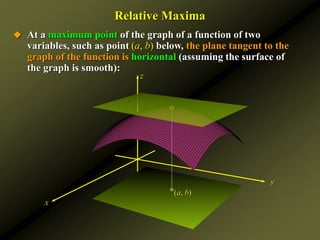

- Maxima and minima of functions of several variables

- Double integrals and constrained maxima/minima using Lagrange multipliers

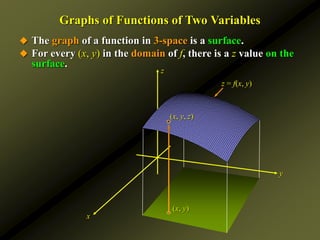

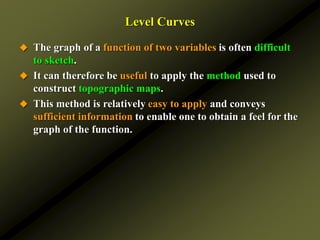

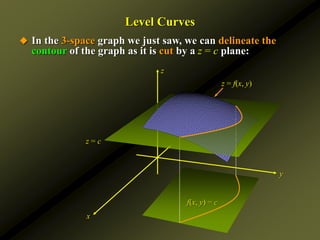

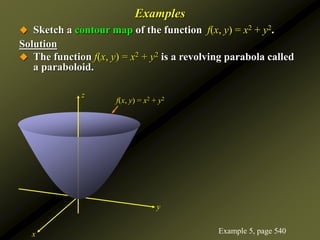

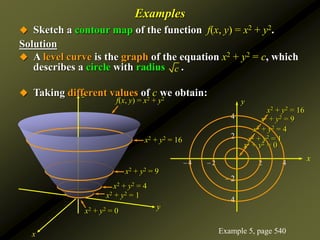

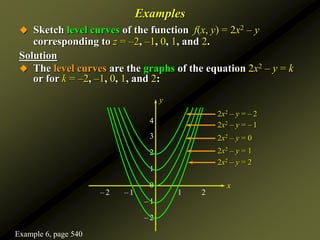

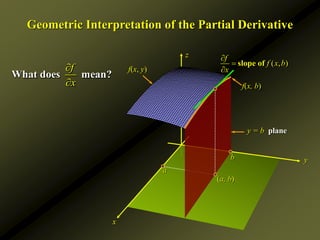

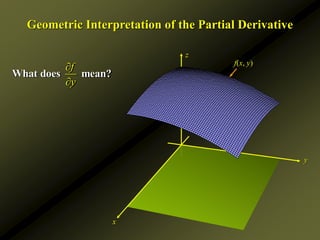

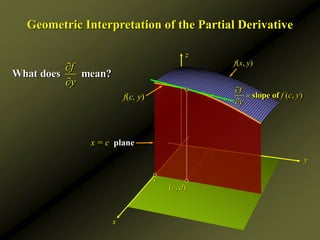

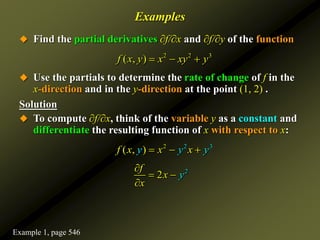

It provides examples of computing partial derivatives of functions, interpreting them geometrically, and using partial derivatives to determine rates of change. Level curves are also discussed as a way to sketch graphs of functions of two variables.

![Examples

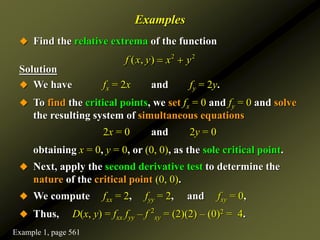

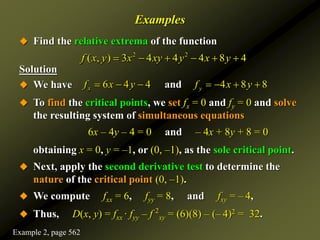

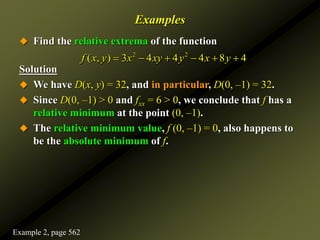

Find the relative extrema of the function

Solution

Apply the second derivative test to the critical point (0, –1):

We have D(x, y) = 48(y – 1).

In particular, D(0, –1) = 48[(–1) – 1] = – 96.

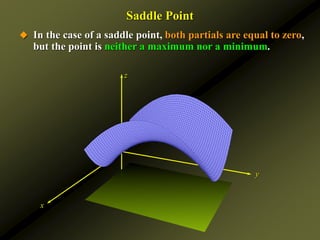

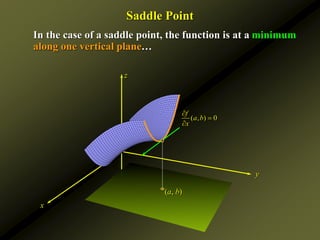

Since D(0, –1) = – 96 < 0 we conclude that f has a saddle

point at (0, –1).

The saddle point value is f (0, –1) = 22, so there is a saddle

point at (0, –1, 22).

3 2 2

( , ) 4 12 36 2

f x y y x y y

Example 3, page 562](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pubch08-221128235749-85e3f6de/85/Calculusseveralvariables-ppt-77-320.jpg)

![Examples

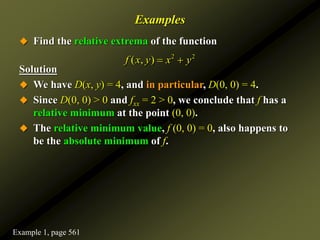

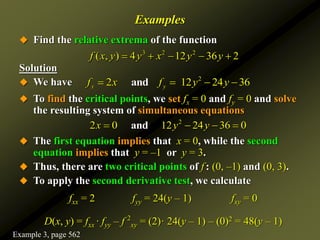

Find the relative extrema of the function

Solution

Apply the second derivative test to the critical point (0, 3):

We have D(x, y) = 48(y – 1).

In particular, D(0, 3) = 48[(3) – 1] = 96.

Since D(0, –1) = 96 > 0 and fxx (0, 3) = 2 > 0, we conclude that

f has a relative minimum at the point (0, 3).

The relative minimum value, f (0, 3) = –106, so there is a

relative minimum at (0, 3, –106).

3 2 2

( , ) 4 12 36 2

f x y y x y y

Example 3, page 562](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pubch08-221128235749-85e3f6de/85/Calculusseveralvariables-ppt-78-320.jpg)

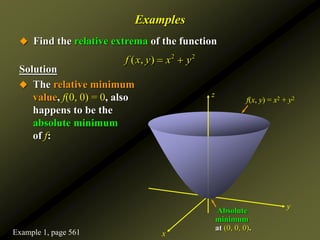

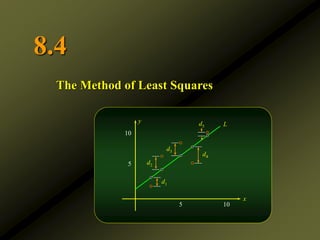

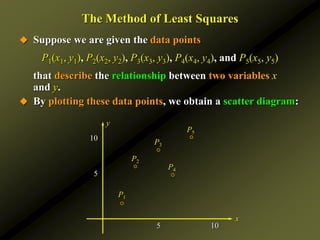

![The Method of Least Squares

Observe that

This may be viewed as a function of two variables m and b.

Thus, the least-squares criterion is equivalent to minimizing

the function

2 2 2 2 2

1 2 3 4 5

d d d d d

2 2 2

1 1 2 2 3 3

2 2

4 4 5 5

[ ( ) ] [ ( ) ] [ ( ) ]

[ ( ) ] [ ( ) ]

f x y f x y f x y

f x y f x y

2 2 2

1 1 2 2 3 3

2 2

4 4 5 5

[ ] [ ] [ ]

[ ] [ ]

mx b y mx b y mx b y

mx b y mx b y

2 2 2

1 1 2 2 3 3

2 2

4 4 5 5

( , ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( )

f m b mx b y mx b y mx b y

mx b y mx b y

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pubch08-221128235749-85e3f6de/85/Calculusseveralvariables-ppt-89-320.jpg)

![The Method of Least Squares

We want to minimize

We first find the partial derivative with respect to m:

1 1 1 2 2 2 3 3 3

4 4 4 5 5 5

2( ) 2( ) 2( )

2( ) 2( )

f

mx b y x mx b y x mx b y x

m

mx b y x mx b y x

2 2 2

1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3

2 2

4 4 4 4 5 5 5 5

2[

]

mx bx y x mx bx y x mx bx y x

mx bx y x mx bx y x

2 2 2 2 2

1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5

2[( ) ( )

( )]

x x x x x m x x x x x b

y x y x y x y x y x

2 2 2

1 1 2 2 3 3

2 2

4 4 5 5

( , ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( )

f m b mx b y mx b y mx b y

mx b y mx b y

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pubch08-221128235749-85e3f6de/85/Calculusseveralvariables-ppt-90-320.jpg)

![The Method of Least Squares

We want to minimize

We now find the partial derivative with respect to b:

1 1 2 2 3 3

4 4 5 5

2( ) 2( ) 2( )

2( ) 2( )

f

mx b y mx b y mx b y

b

mx b y mx b y

1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5

2[( ) 5 ( )]

x x x x x m b y y y y y

2 2 2

1 1 2 2 3 3

2 2

4 4 5 5

( , ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( )

f m b mx b y mx b y mx b y

mx b y mx b y

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pubch08-221128235749-85e3f6de/85/Calculusseveralvariables-ppt-91-320.jpg)

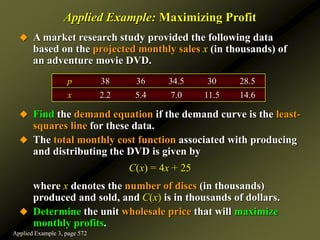

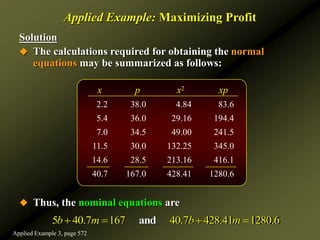

![Solution

To find the absolute maximum of P(x) over the closed

interval [0, 49.37], we compute

Since P(x) = 0 , we find that x ≈ 22.22 as the only critical

point of P.

Finally, from the table

we see that the optimal wholesale price is

or $21.99 per disc.

Applied Example: Maximizing Profit

( ) 1.62 35.99

P x x

x 0 22.22 49.37

P(x) –25 374.78 – 222.47

0.81(22.22) 39.99 21.99

p

Applied Example 3, page 572](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pubch08-221128235749-85e3f6de/85/Calculusseveralvariables-ppt-103-320.jpg)

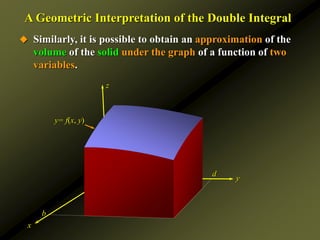

![ You may recall that we can do a Riemann sum to

approximate the area under the graph of a function of one

variable by adding the areas of the rectangles that form

below the graph resulting from small increments of x (x)

within a given interval [a, b]:

x

y

A Geometric Interpretation of the Double Integral

y= f(x)

a b

x](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pubch08-221128235749-85e3f6de/85/Calculusseveralvariables-ppt-120-320.jpg)

![Theorem 1

Evaluating a Double Integral Over a Plane Region

a. Suppose g1(x) and g2(x) are continuous functions on [a, b] and

the region R is defined by R = {(x, y)| g1(x) y g2(x); a x b}.

Then,

2

1

( )

( )

( , ) ( , )

b g x

R a g x

f x y dA f x y dy dx

x

y

a b

y = g1(x)

y = g2(x)

R](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pubch08-221128235749-85e3f6de/85/Calculusseveralvariables-ppt-126-320.jpg)

![Theorem 1

Evaluating a Double Integral Over a Plane Region

b. Suppose h1(y) and h2(y) are continuous functions on [c, d] and

the region R is defined by R = {(x, y)| h1(y) x h2(y); c y d}.

Then,

2

1

( )

( )

( , ) ( , )

d h y

R c h y

f x y dA f x y dx dy

x

y

c

d

x = h1(y) x = h2(y)

R](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pubch08-221128235749-85e3f6de/85/Calculusseveralvariables-ppt-127-320.jpg)