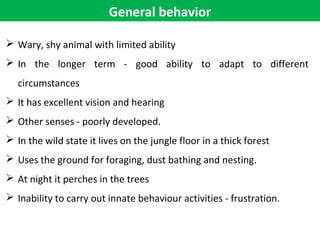

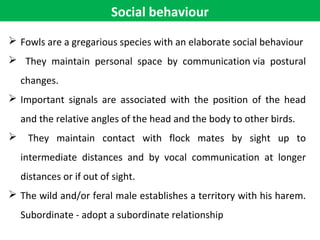

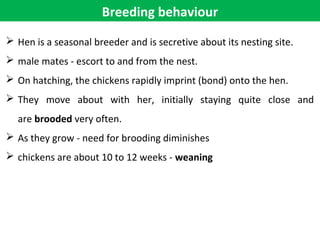

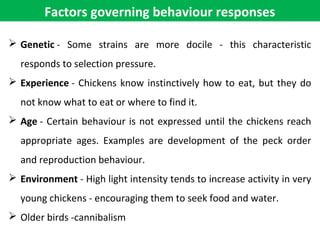

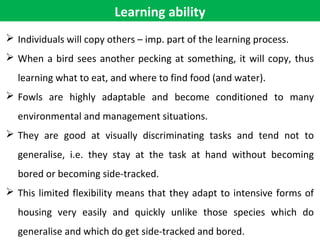

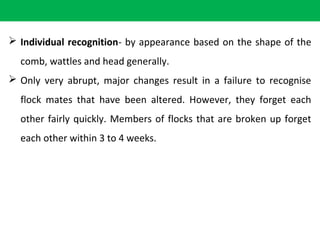

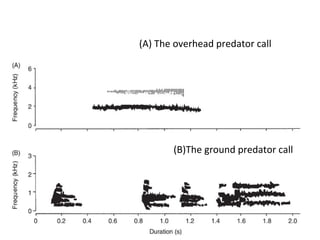

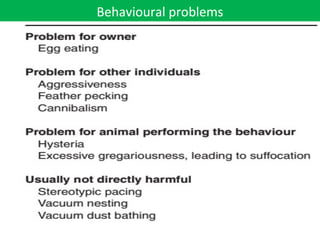

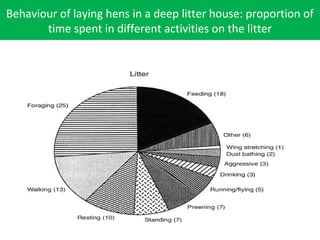

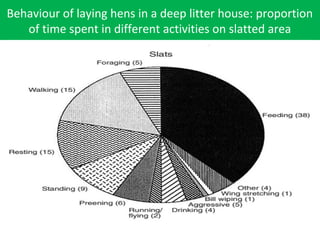

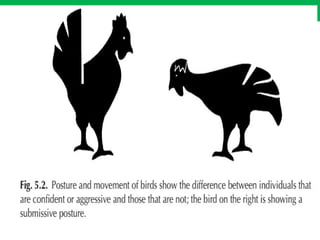

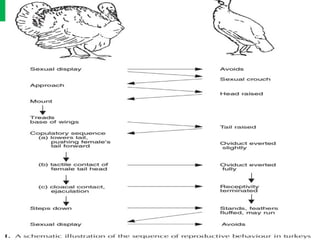

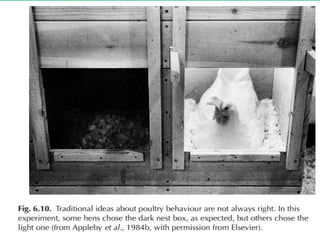

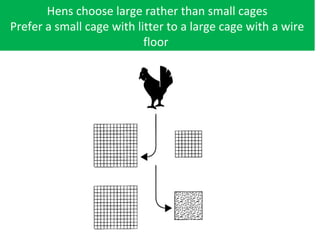

Poultry exhibit complex social behaviors including establishing hierarchies, communicating through sounds and displays, and reproducing. Their behaviors are influenced by genetic, environmental, and experiential factors. Key behaviors include foraging, dust bathing, nesting, roosting, and responding fearfully to unfamiliar stimuli like humans due to their wary nature. Poultry learn from each other and adapt well to different housing situations through visual learning and conditioning.