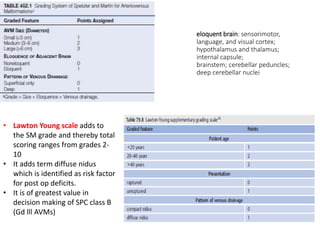

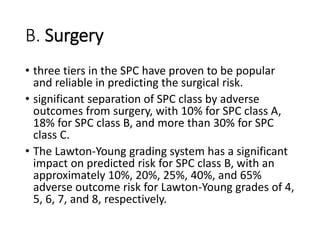

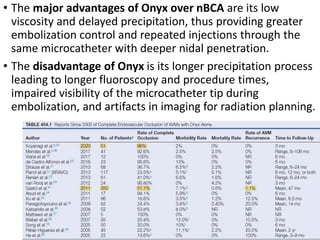

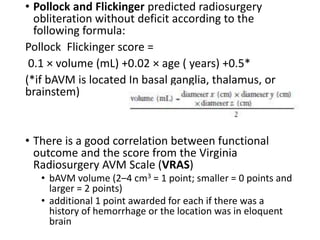

The document discusses the management of brain arteriovenous malformations (BAVMs), which are abnormal connections between cerebral arteries and veins leading to potential hemorrhaging. It highlights various grading systems used to predict treatment outcomes and treatment strategies, including surgery, endovascular methods, and radiosurgery, considering factors like AVM size and location. Recent studies, such as the ARUBA trial, emphasize cautious approaches to treatment, especially for unruptured AVMs, where conservative management may often yield better outcomes.