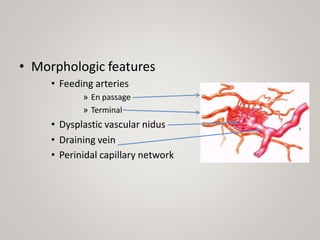

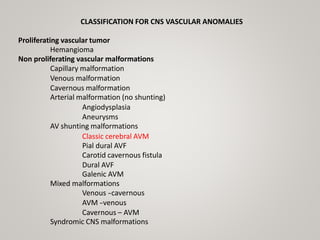

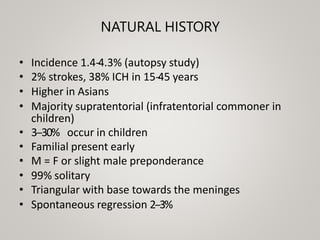

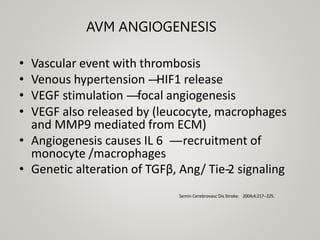

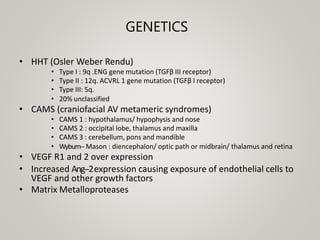

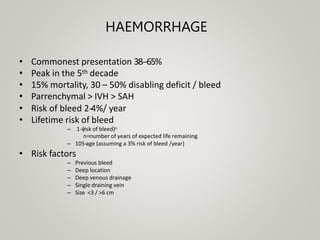

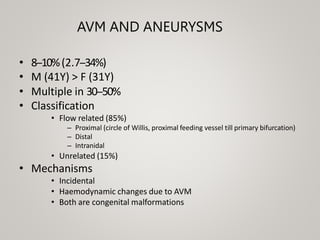

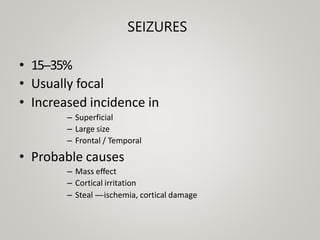

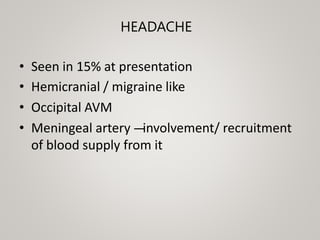

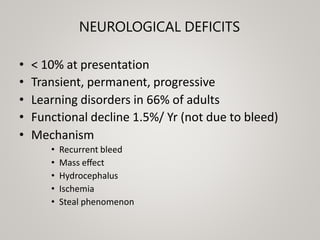

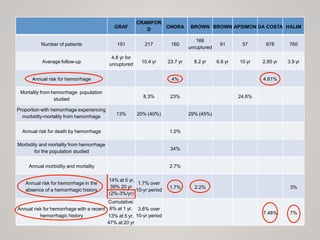

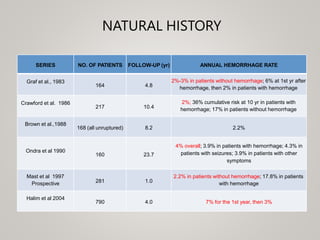

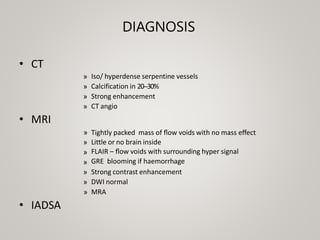

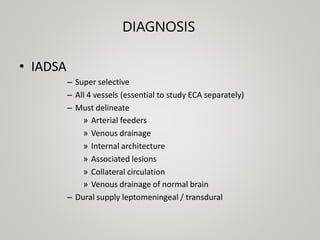

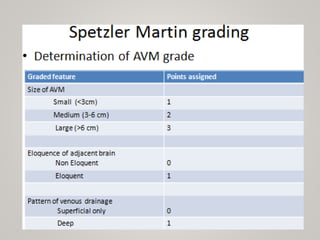

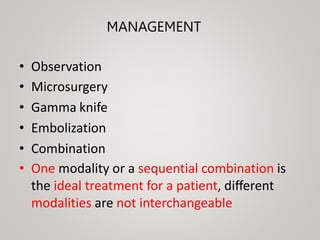

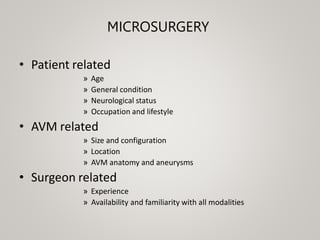

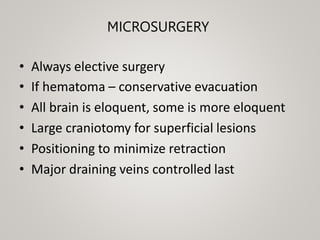

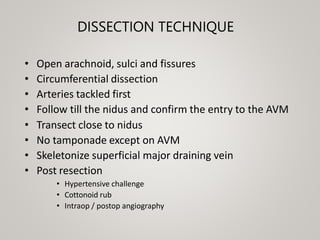

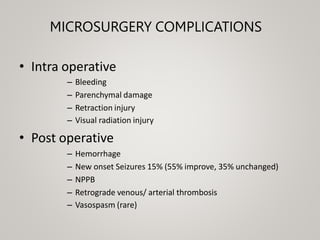

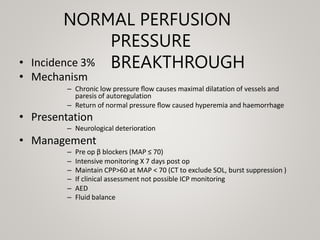

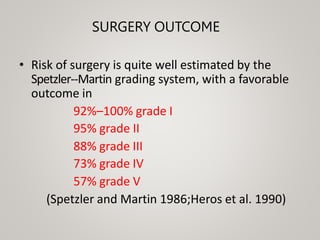

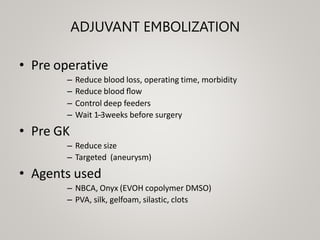

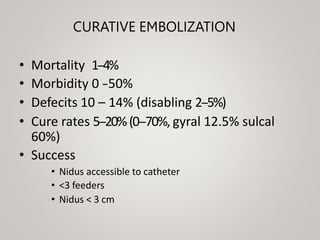

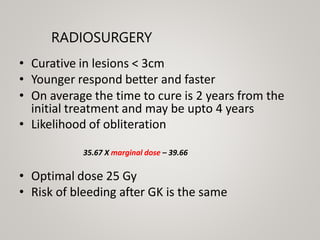

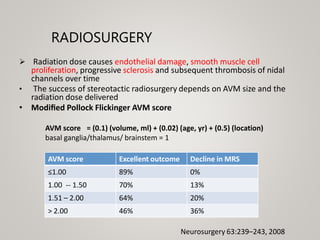

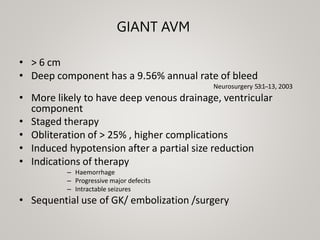

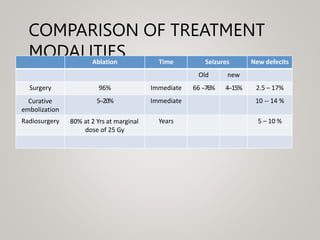

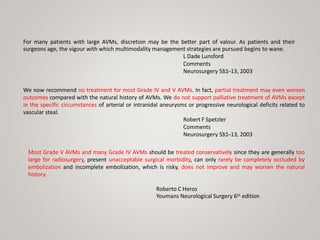

This document discusses cranial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), including their classification, natural history, diagnosis, and management. It notes that AVMs are congenital vascular lesions with high blood flow that can present with hemorrhage, seizures, headaches or neurological deficits. Treatment options include observation, microsurgery, radiosurgery, embolization, or combinations depending on the patient and AVM characteristics. Surgical resection and radiosurgery can cure AVMs but risks depend on their size, location and complexity as defined by scales like the Spetzler-Martin grading system.