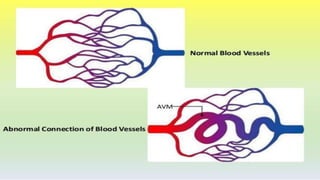

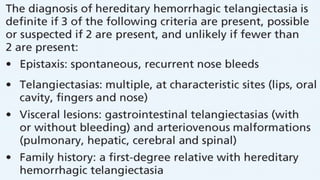

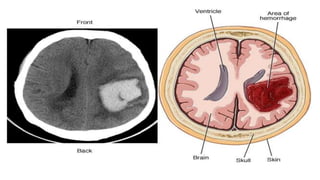

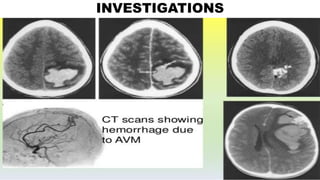

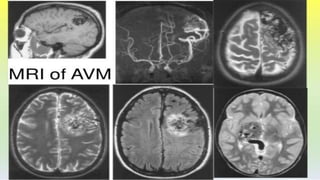

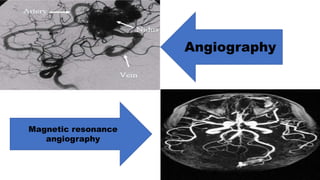

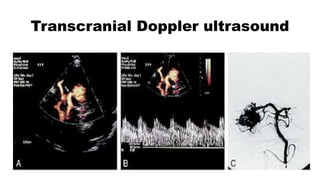

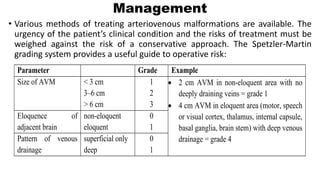

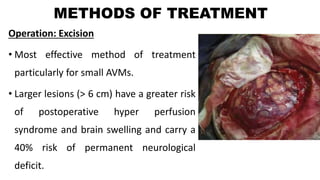

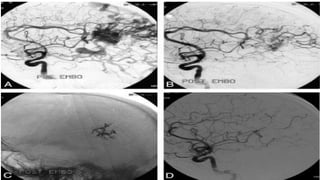

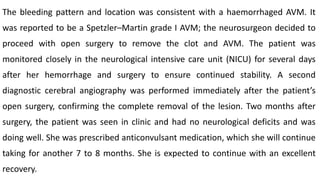

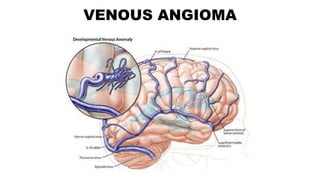

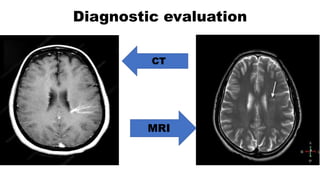

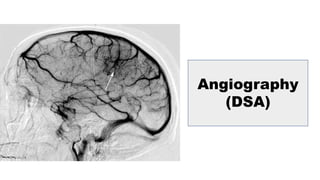

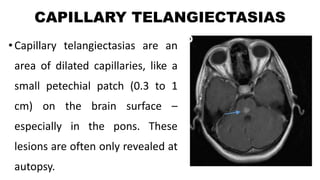

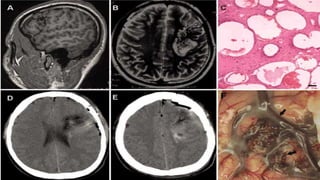

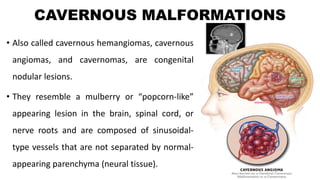

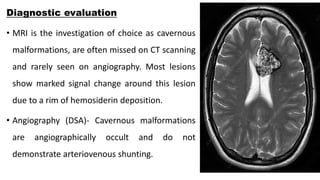

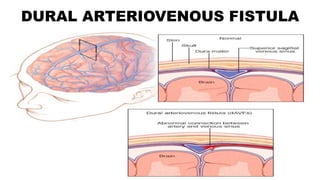

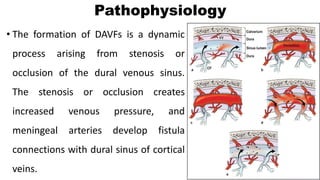

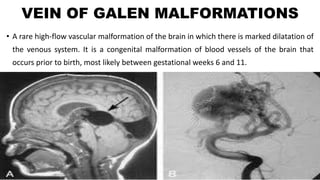

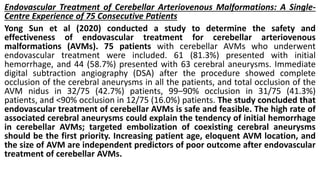

The document discusses cerebrovascular anomalies or malformations, which are conditions characterized by malformed blood vessels that can lead to hemorrhages, stroke, blood clots, and other complications. It covers the classification, epidemiology, clinical presentation, investigations, management, and treatment of various types of cerebrovascular anomalies, including arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), venous angiomas, and cavernous malformations. It also presents a case study example of a patient who experienced bleeding from a left parietal AVM and was treated surgically.