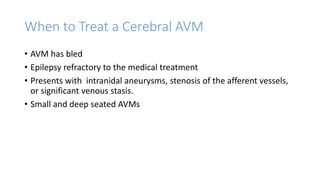

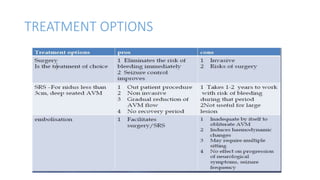

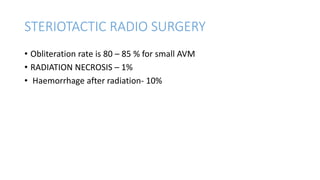

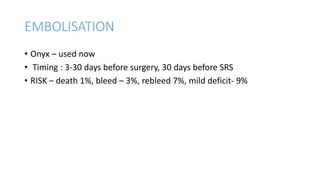

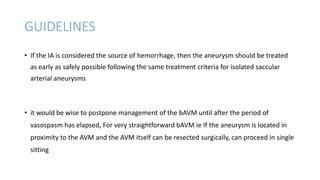

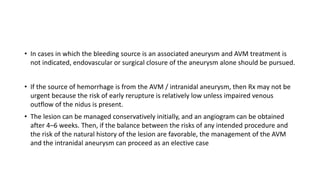

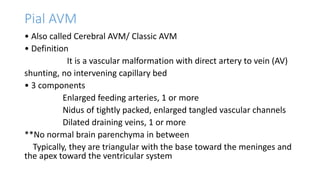

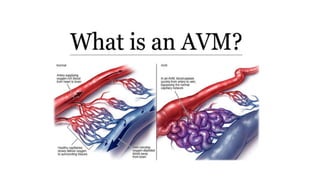

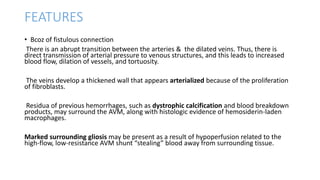

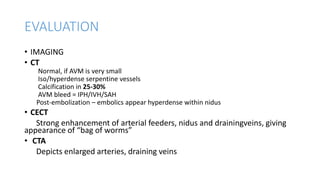

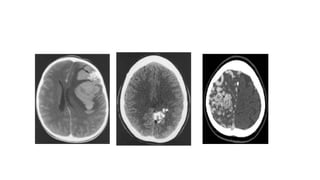

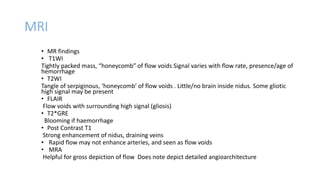

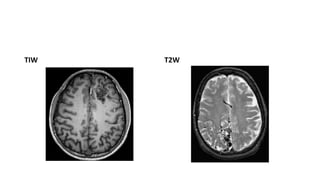

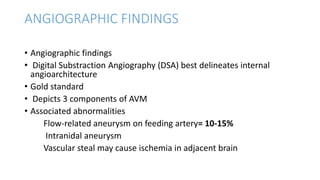

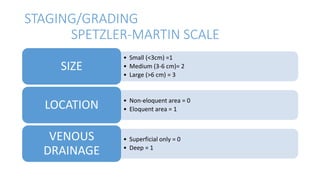

This document provides an overview of cerebral arteriovenous malformations (AVMs). It defines a cerebral AVM as a vascular malformation with direct connections between arteries and veins, without an intervening capillary bed. The key characteristics of AVMs are described, including their demographics, clinical presentations such as hemorrhage and seizures, evaluation with imaging and angiography, grading systems like the Spetzler-Martin scale, and treatment options including surgery, embolization, and radiosurgery. Guidelines for treatment are outlined based on the grade of the AVM, with lower grade AVMs more amenable to aggressive treatment aiming for cure.

![CUMULATIVE RISK

expected years of remaining life

• Risk of bleeding [ atleast once] =1-(annual risk of not bleeding)

• annual risk of not bleeding is = 1 – the annual risk of bleeding.

• OR Risk of bleeding = 105 – age (in years)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/avmnew-190301194350/85/CEREBRAL-ARTERIO-VENOUS-MALFORMATIONS-18-320.jpg)

![• Grade = total points 1-5

• Grade 6 –inoperable or not

amenable to any treatment

modality

• Good surgical outcome with

respect to SM grading [heros et

al]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/avmnew-190301194350/85/CEREBRAL-ARTERIO-VENOUS-MALFORMATIONS-28-320.jpg)