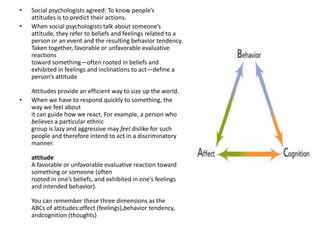

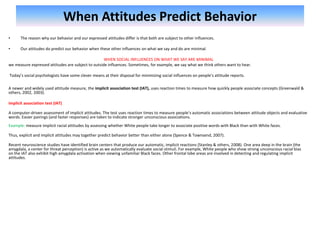

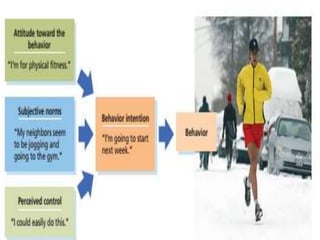

This document discusses attitudes and their relationship to behavior. It notes that social psychologists have found attitudes can predict actions, as attitudes incorporate beliefs, feelings, and behavioral tendencies. However, research by Allan Wicker found that expressed attitudes often did not closely predict actual behaviors in many situations, such as attitudes toward cheating not matching cheating behaviors. The document explains that attitudes better predict behavior when other social influences are minimized and when the measured attitude closely matches the specific behavior examined. Implicit association tests can better capture unconscious attitudes that may predict behavior along with explicit attitudes.