The document discusses how our sense of self is shaped by our social world through three main points:

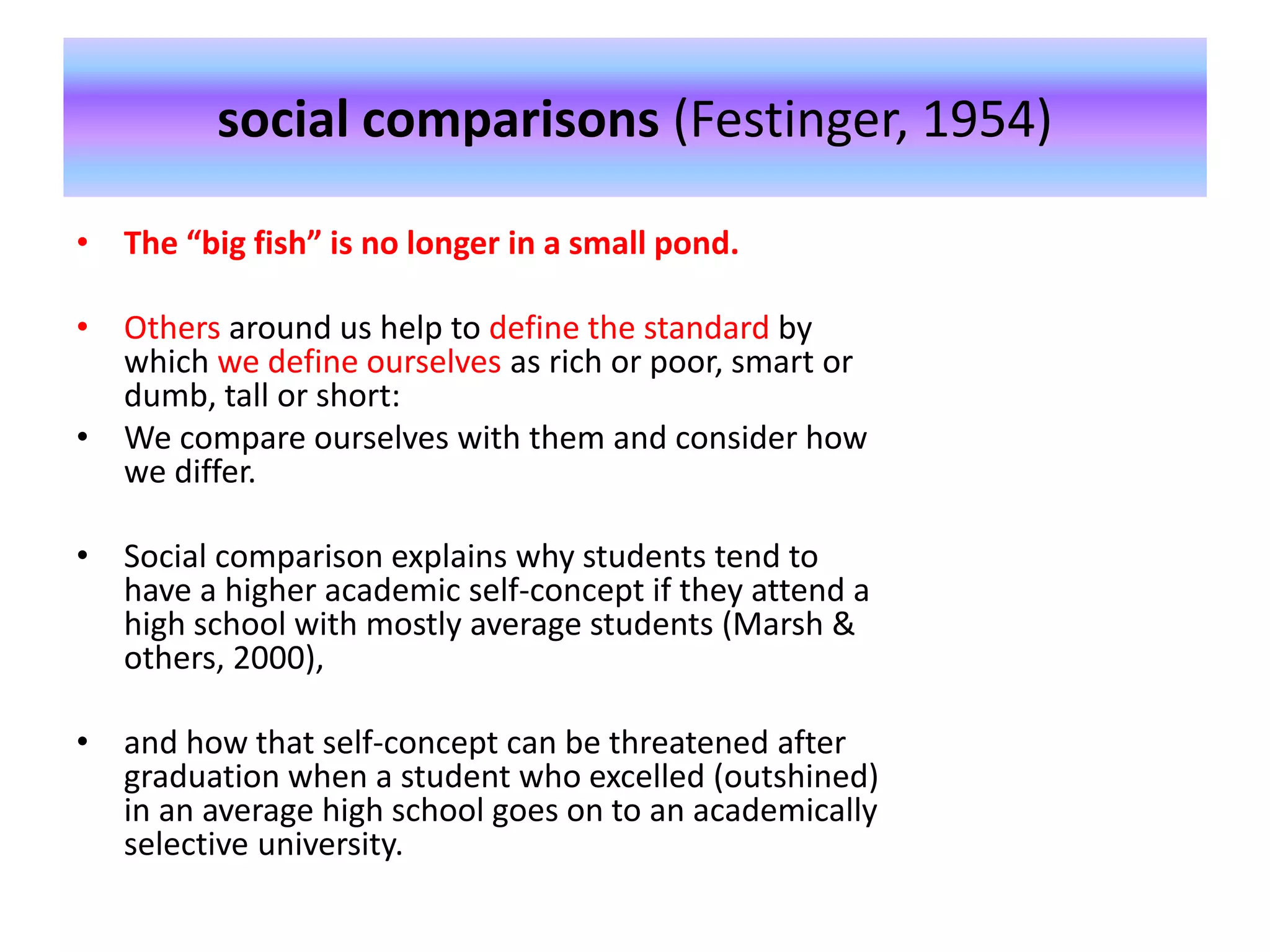

1. Our social surroundings, such as the roles we play and social comparisons we make, influence how we develop our self-concept and see ourselves. Playing new roles can change how we think about ourselves, and comparing ourselves to others helps define our self-image.

2. Our experiences of success, failure, and how others judge us also impact our self-concept. Succeeding at challenges boosts our self-esteem while failures can diminish it. Others' positive views of us can help us see ourselves positively as well.

3. Culture provides social identities and expectations that shape our understanding of