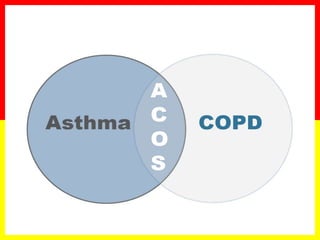

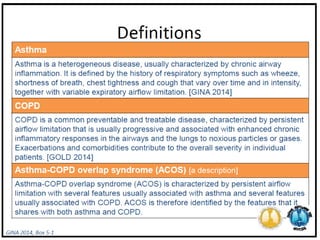

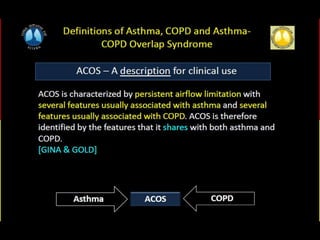

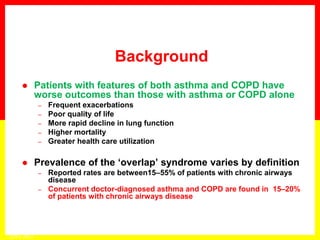

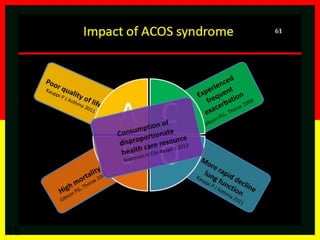

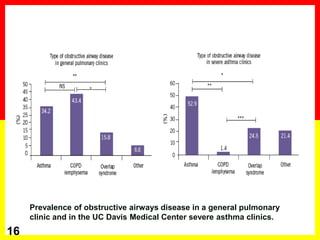

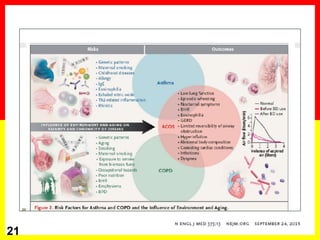

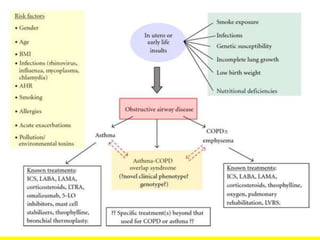

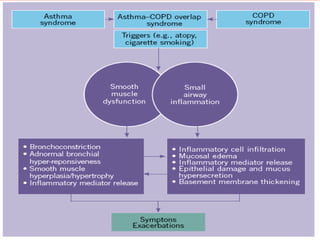

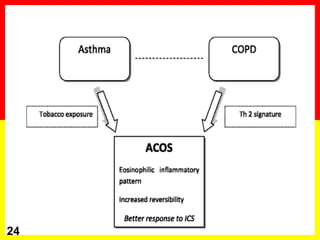

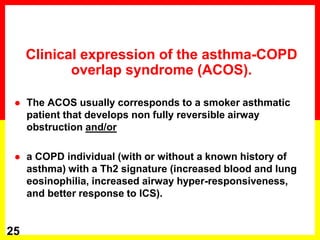

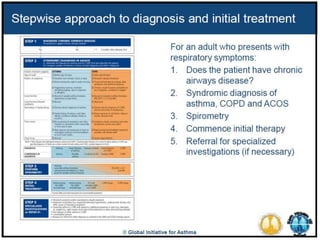

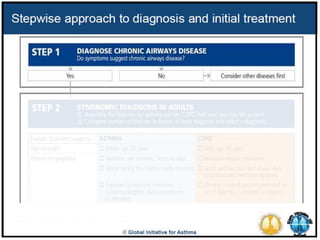

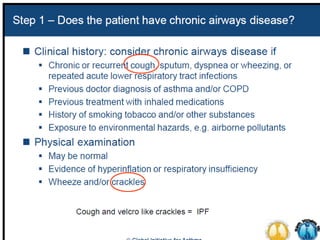

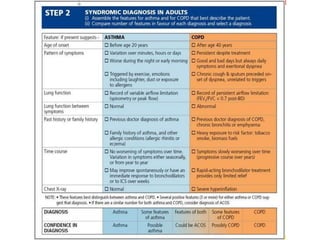

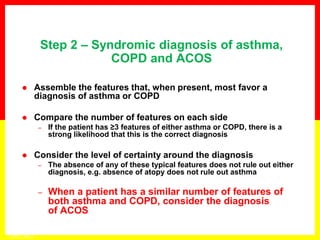

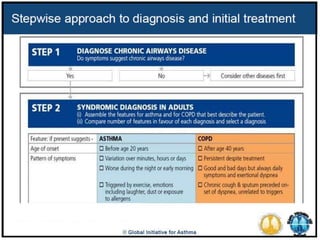

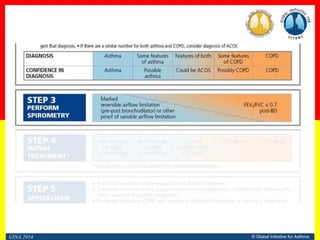

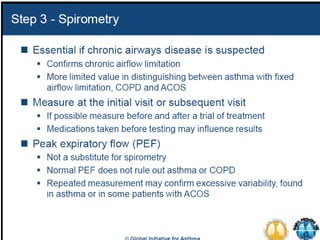

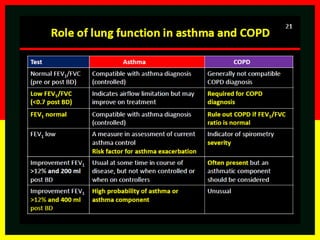

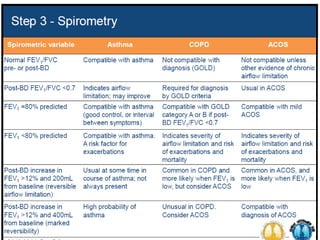

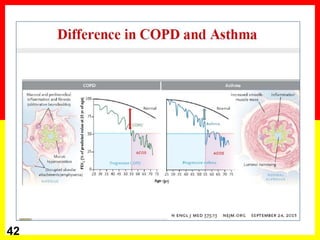

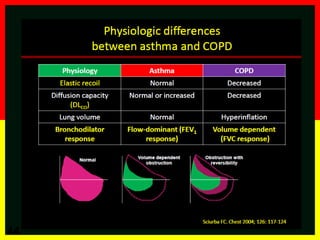

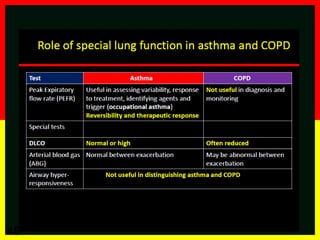

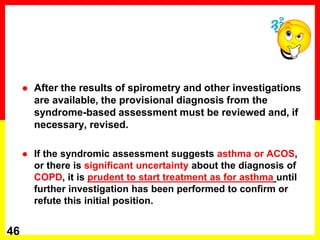

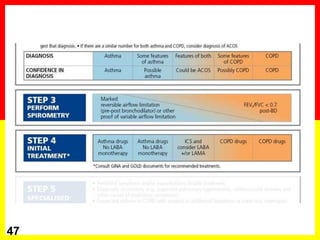

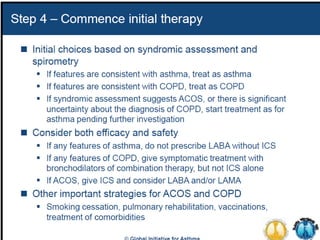

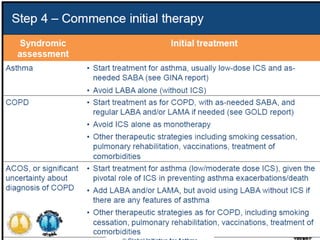

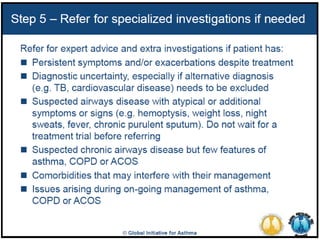

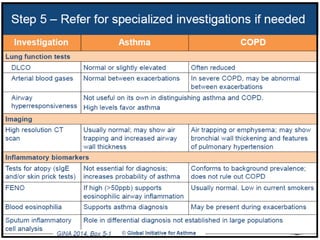

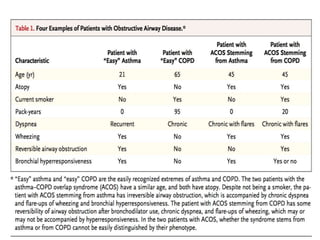

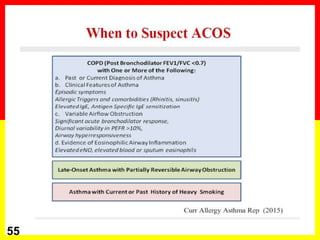

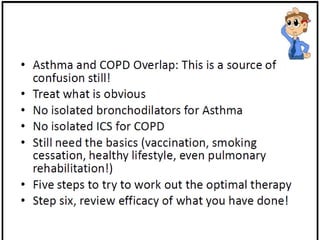

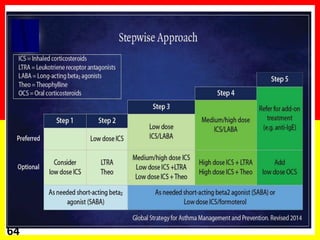

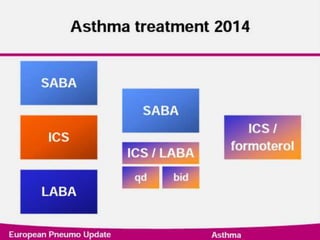

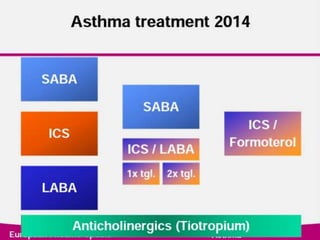

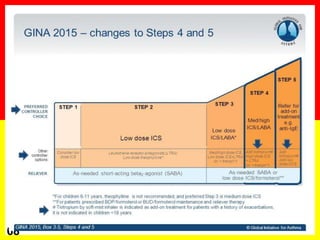

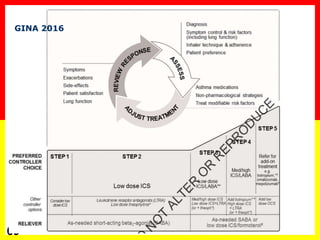

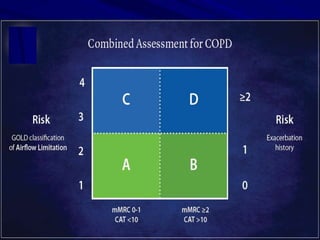

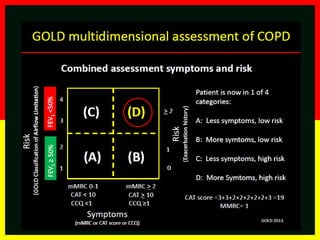

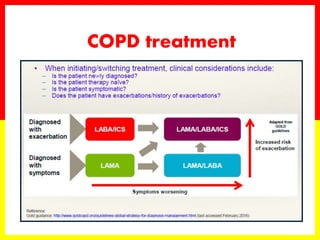

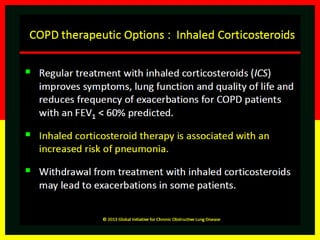

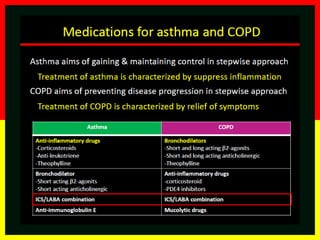

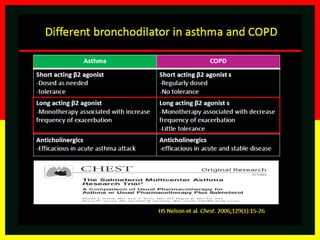

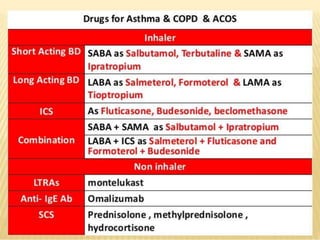

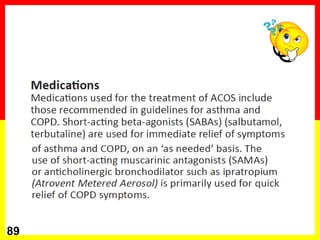

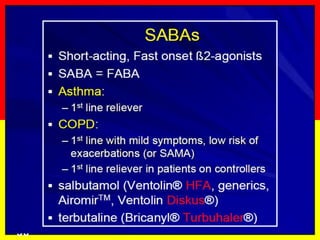

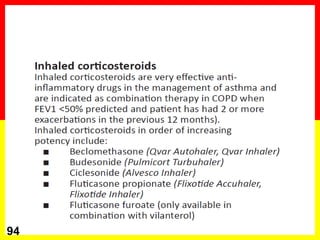

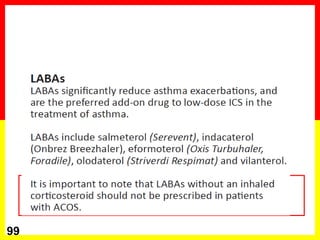

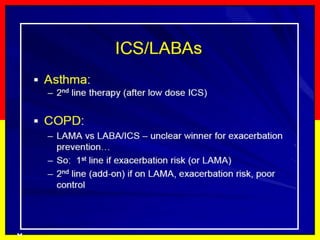

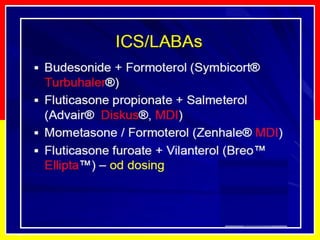

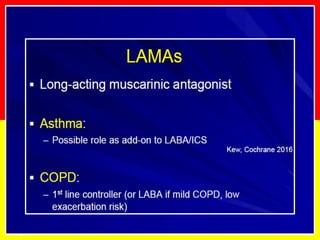

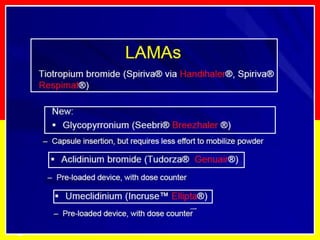

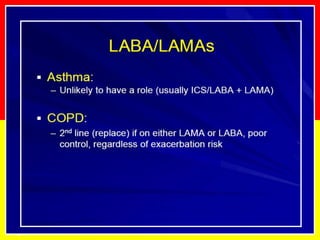

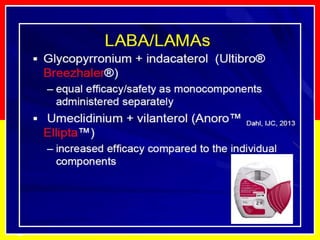

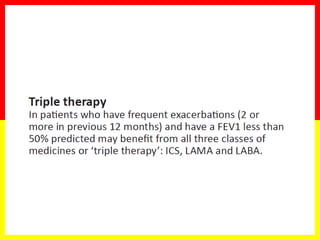

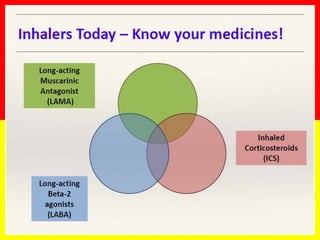

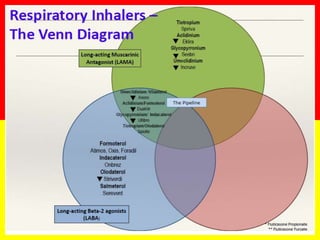

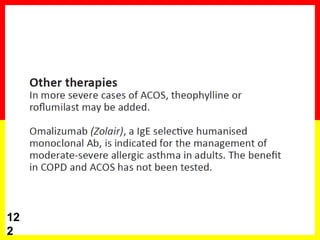

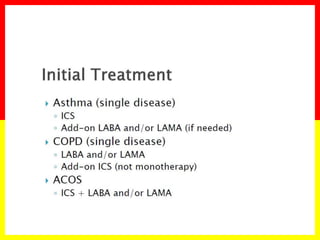

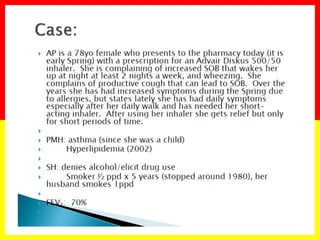

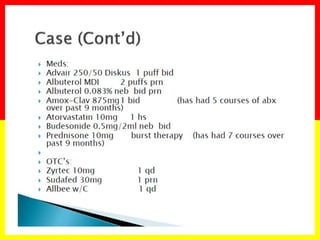

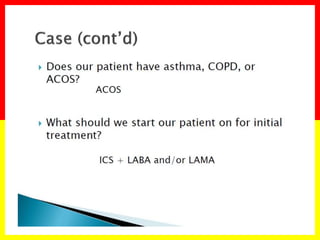

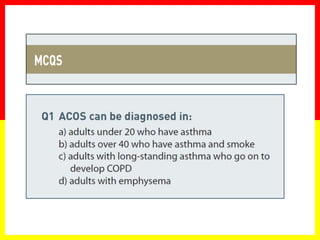

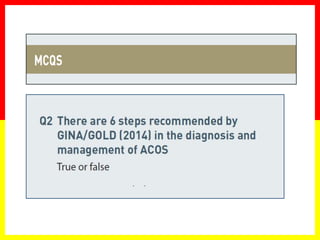

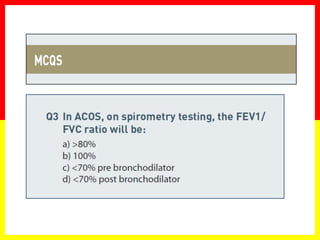

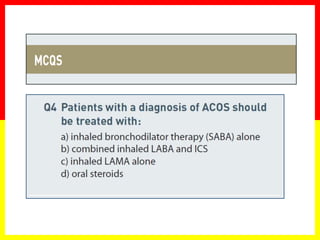

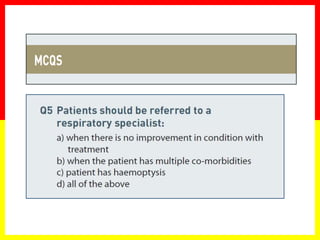

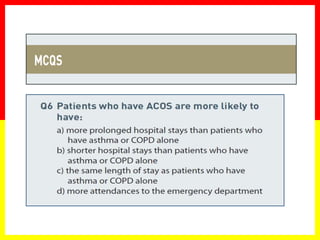

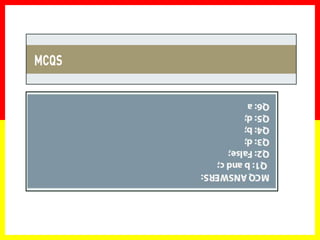

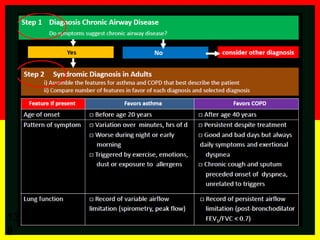

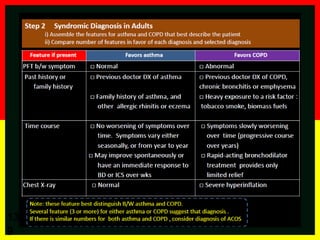

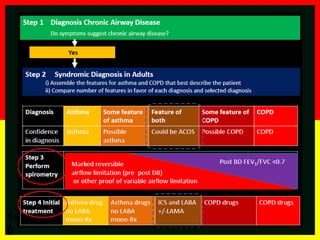

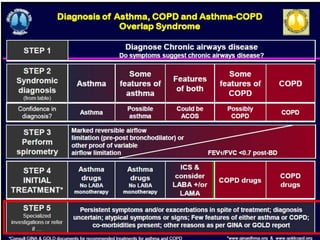

This document provides an overview of asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS). It discusses how asthma and COPD were traditionally viewed as distinct conditions but some patients exhibit features of both. Patients with ACOS have worse health outcomes than those with asthma or COPD alone. The document reviews clinical features of ACOS and provides guidance on diagnosing patients based on their symptoms, lung function tests, and other features. It also discusses treatment approaches for ACOS.