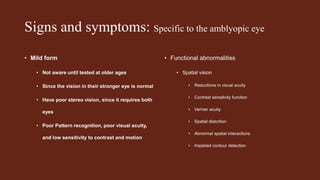

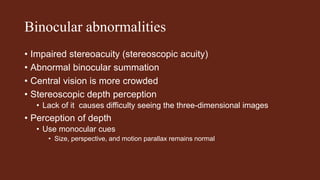

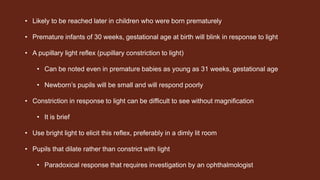

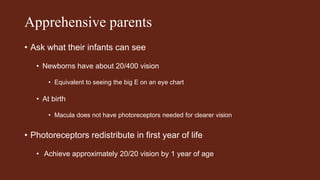

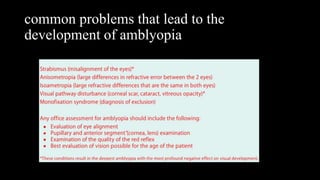

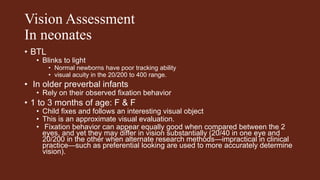

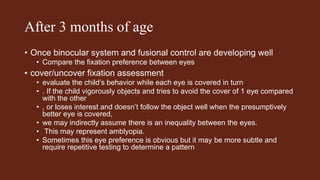

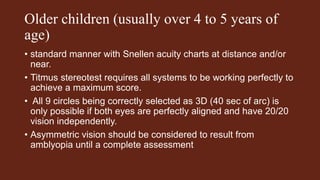

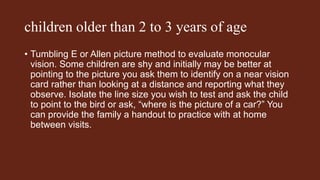

Amblyopia is a developmental problem in the brain caused by inadequate visual stimulation early in life, typically due to strabismus, high refractive error, or deprivation of vision. It results in reduced visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and stereoacuity in the affected eye. Early diagnosis is important to prevent amblyopia, as treatment success declines after age 5. Screening exams for infants and children include assessing eye alignment, eye movements, pupil light reflexes, visual acuity, and stereoacuity to detect common causes of amblyopia such as strabismus.