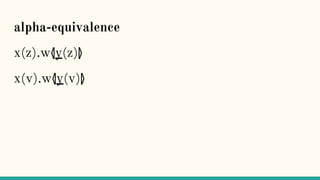

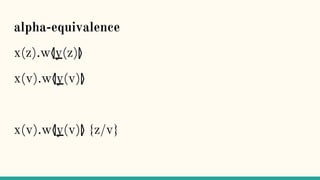

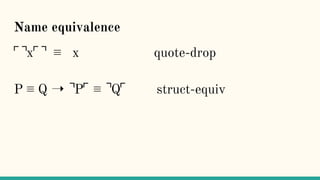

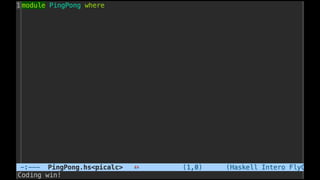

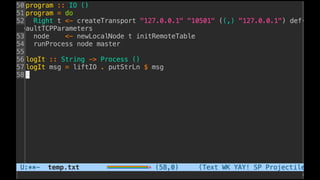

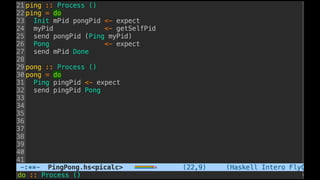

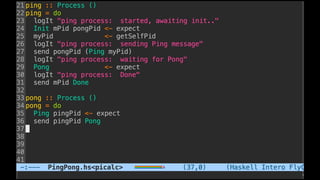

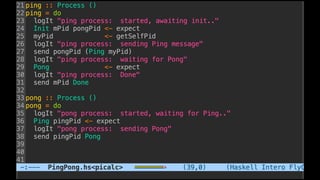

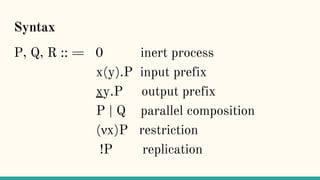

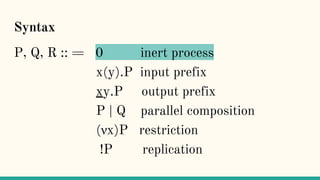

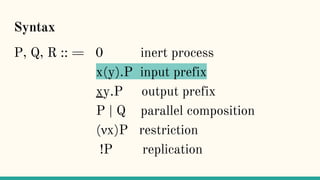

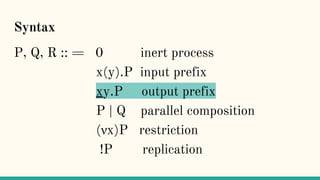

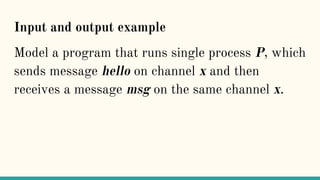

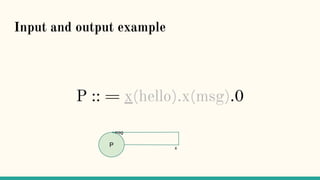

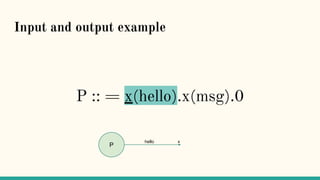

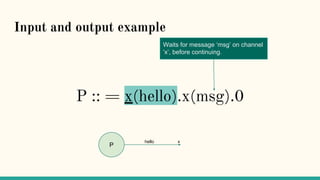

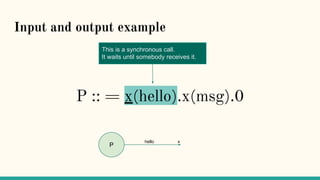

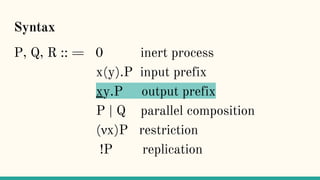

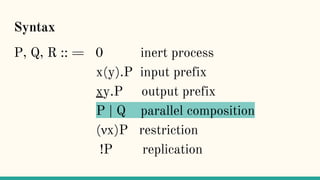

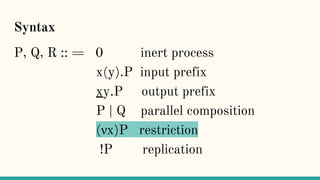

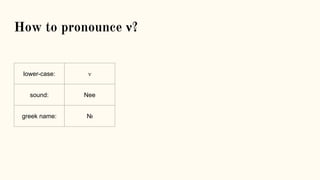

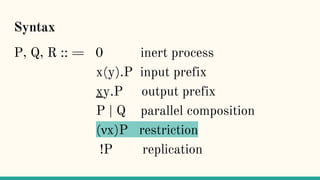

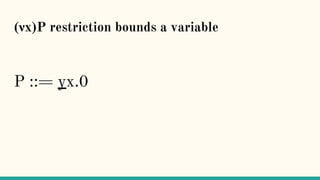

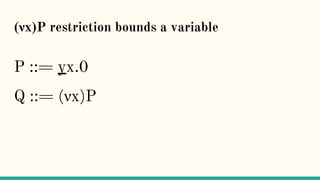

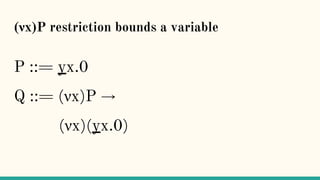

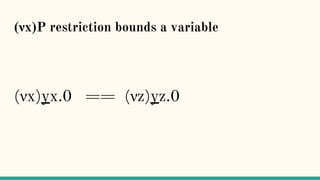

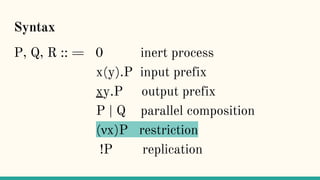

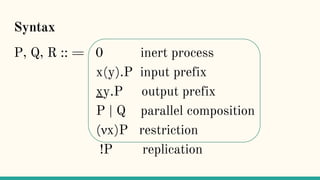

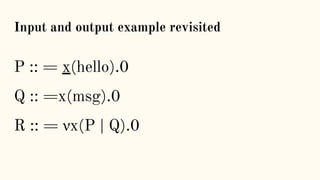

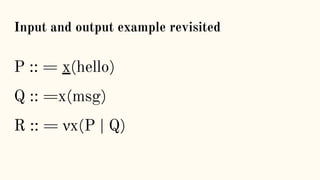

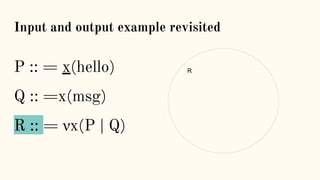

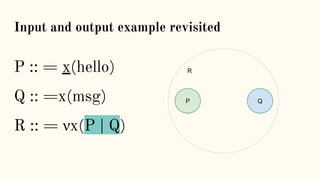

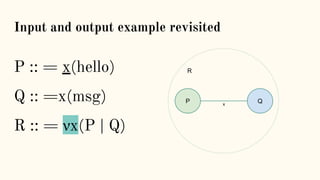

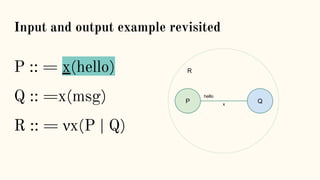

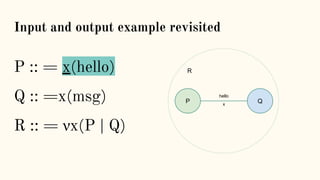

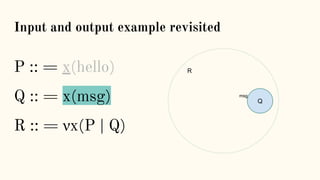

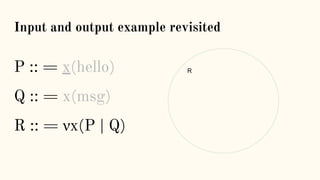

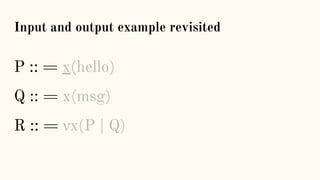

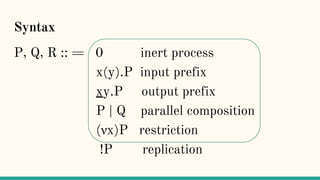

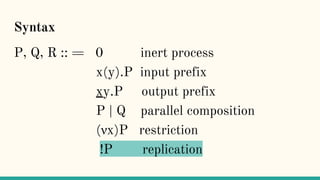

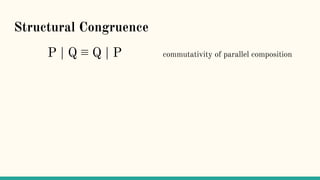

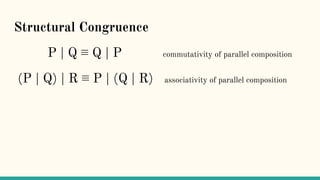

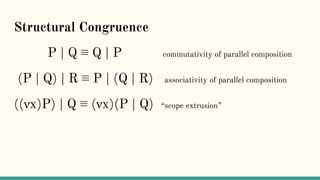

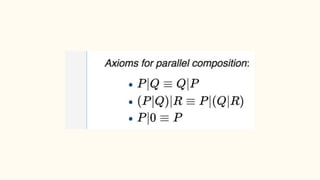

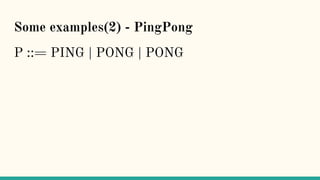

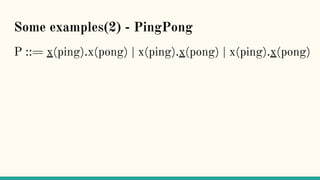

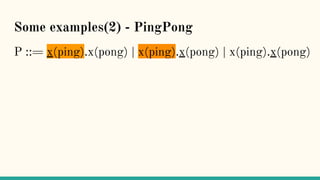

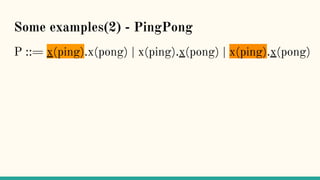

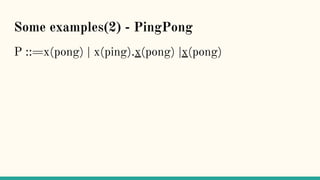

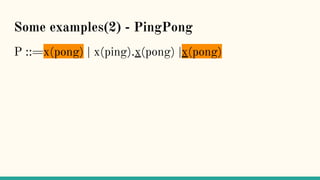

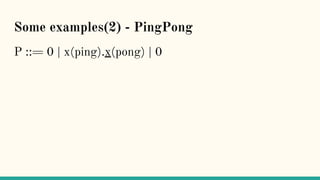

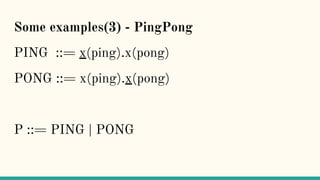

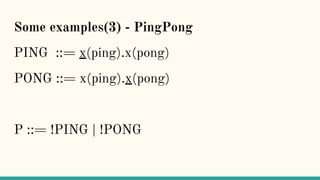

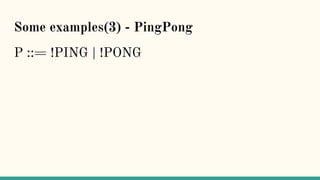

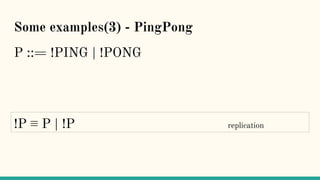

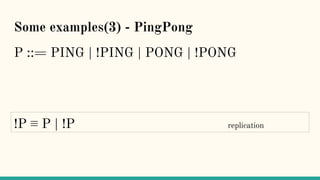

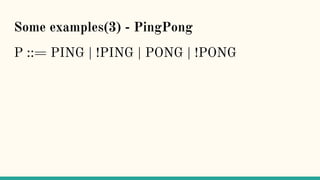

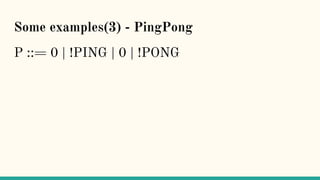

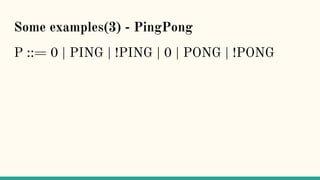

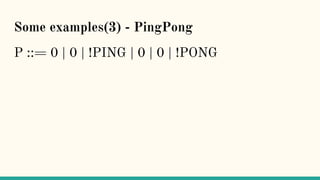

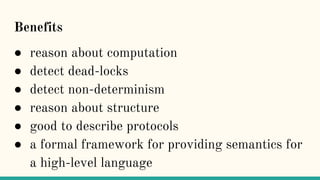

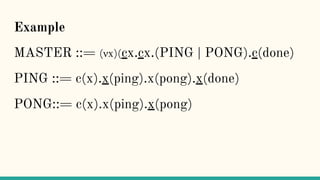

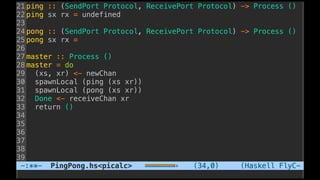

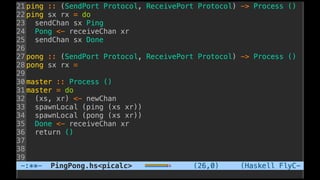

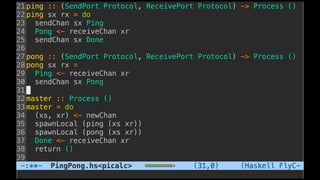

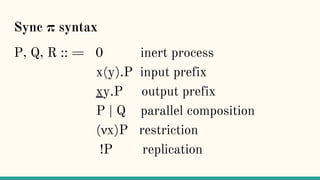

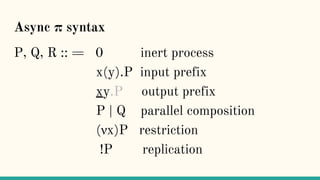

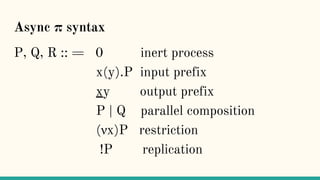

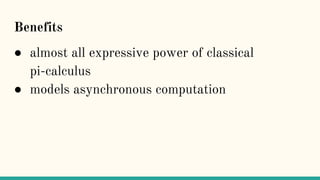

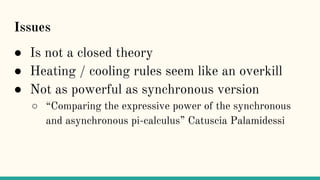

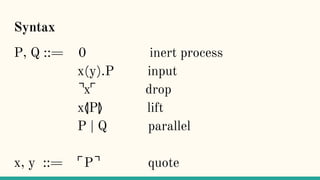

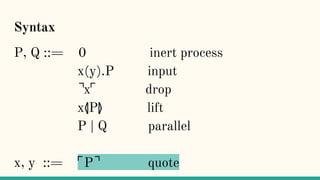

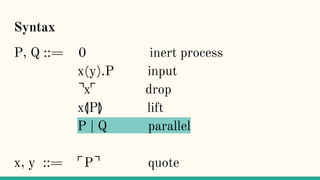

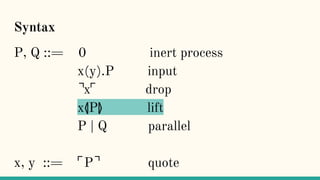

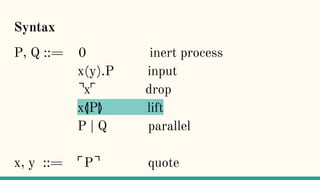

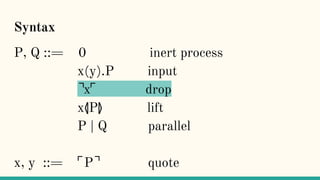

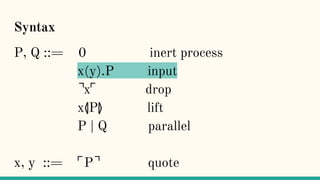

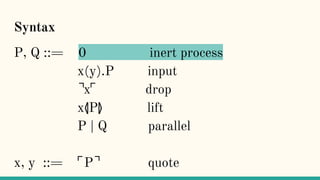

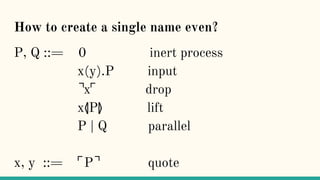

The document discusses distributed calculi and the pi-calculus in particular. It begins with an overview of the pi-calculus syntax including processes, input/output prefixes, parallel composition, restriction and replication. Examples are given to demonstrate communication between processes using input/output prefixes. Structural congruence and reduction rules are also covered. The document concludes with an example of modeling a simple ping-pong protocol in pi-calculus.

![Is there a calculus for distributed computing?

“The inevitability of the lambda-calculus arises

from the fact that the only way to observe a

functional computation is to watch which output

values it yields when presented with different

input values” [1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-97-320.jpg)

![Is there a calculus for distributed computing?

“Unfortunately, the world of concurrent

computation is not so orderly. Different notions of

what can be observed may be appropriate in

different circumstances, giving rise to different

definitions of when two concurrent systems have

‘the same behavior’ ” [1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-98-320.jpg)

![CCS & CSP

CCS - Calculus of Communicating Systems [3]

CSP - Communicating Sequential Processes [4]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-100-320.jpg)

![What is π-calculus

“π -calculus is a model of computation for

concurrent systems.” [2]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-102-320.jpg)

![What is π-calculus

“In lambda-calculus everything is a function (...)

In the pi-calculus every expression denotes a

process - a free-standing computational activity,

running in parallel with other process.” [1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-103-320.jpg)

![What is π-calculus

“Two processes can interact by exchanging a

message on a channel” [1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-104-320.jpg)

![What is π-calculus

“It lets you represent processes, parallel

composition of processes, synchronous

communication between processes through

channels, creation of fresh channels, replication of

processes, and nondeterminism.” [2]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-105-320.jpg)

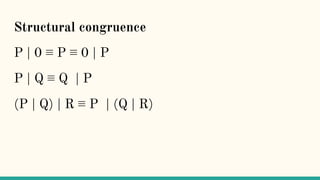

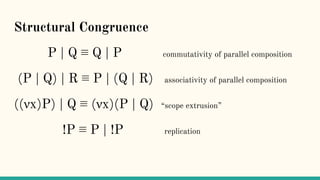

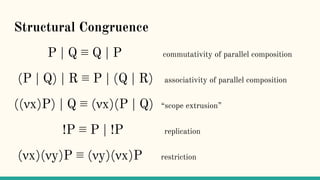

![Structural Congruence

“Two processes are structurally congruent, if they

are identical up to structure.” [5]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-148-320.jpg)

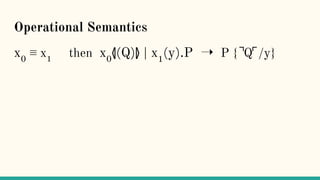

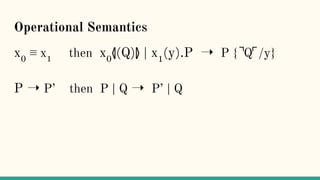

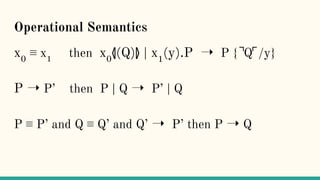

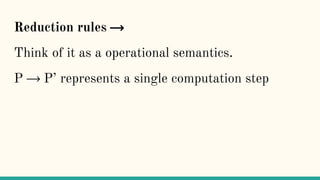

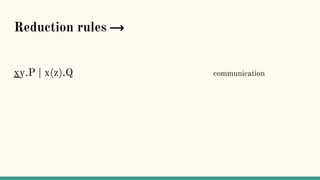

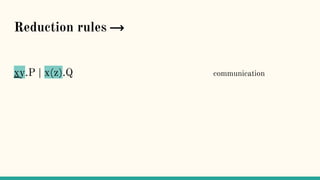

![Reduction rules ⟶

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-157-320.jpg)

![Reduction rules ⟶

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication

P | R → if P → Q reduction under |](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-158-320.jpg)

![Reduction rules ⟶

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication

P | R → Q | R if P → Q reduction under |](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-159-320.jpg)

![Reduction rules ⟶

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication

P | R → Q | R if P → Q reduction under |

(νx)P → if P → Q reduction under ν](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-160-320.jpg)

![Reduction rules ⟶

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication

P | R → Q | R if P → Q reduction under |

(νx)P → (νx)Q if P → Q reduction under ν](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-161-320.jpg)

![Reduction rules ⟶

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication

P | R → Q | R if P → Q reduction under |

(νx)P → (νx)Q if P → Q reduction under ν

P → if P ≡ P’ Q’ ≡ Q structural congruence](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-162-320.jpg)

![Reduction rules ⟶

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication

P | R → Q | R if P → Q reduction under |

(νx)P → (νx)Q if P → Q reduction under ν

P → if P ≡ P’ → Q’ ≡ Q structural congruence](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-163-320.jpg)

![Reduction rules ⟶

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication

P | R → Q | R if P → Q reduction under |

(νx)P → (νx)Q if P → Q reduction under ν

P → Q if P ≡ P’ → Q’ ≡ Q structural congruence](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-164-320.jpg)

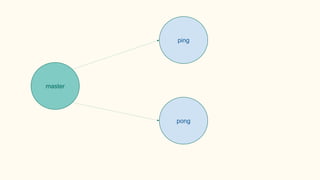

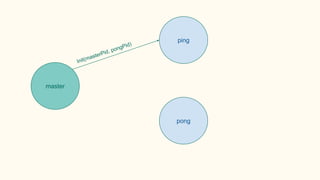

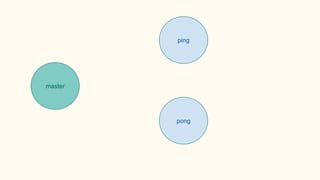

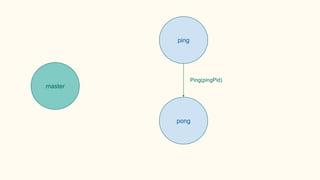

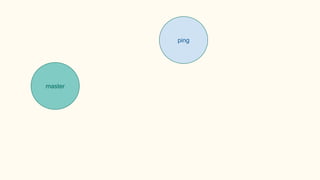

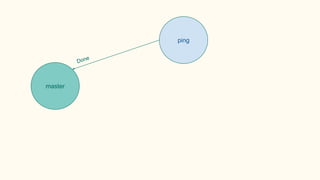

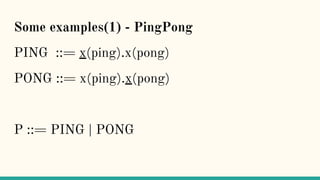

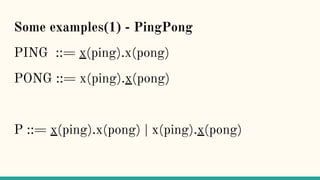

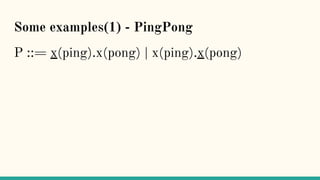

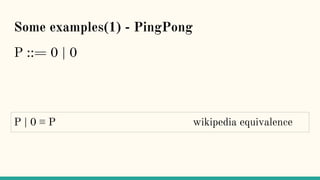

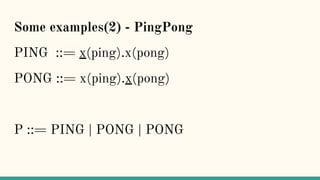

![Some examples(1) - PingPong

P ::= x(ping).x(pong) | x(ping).x(pong)

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-168-320.jpg)

![Some examples(1) - PingPong

P ::= x(ping).x(pong) | x(ping).x(pong)

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-169-320.jpg)

![Some examples(1) - PingPong

P ::= x(ping).x(pong) | x(ping).x(pong)

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-170-320.jpg)

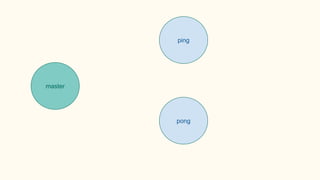

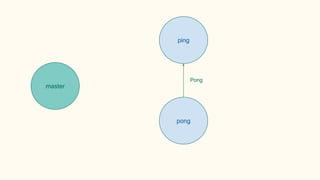

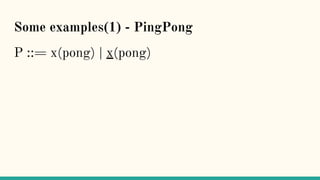

![Some examples(1) - PingPong

P ::= x(pong) | x(pong)

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-171-320.jpg)

![Some examples(1) - PingPong

P ::= x(pong) | x(pong)

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-173-320.jpg)

![Some examples(1) - PingPong

P ::= x(pong) | x(pong)

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-174-320.jpg)

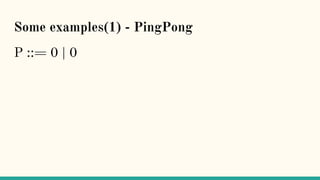

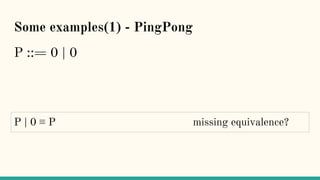

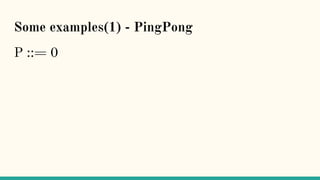

![Some examples(1) - PingPong

P ::= 0 | 0

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-175-320.jpg)

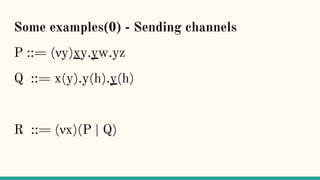

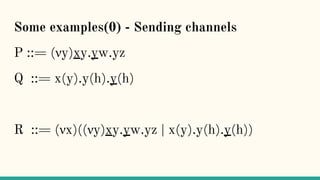

![Some examples(0) - Sending channels

P ::= (νy)xy.yw.yz

Q ::= x(y).y(h).y(h)

R ::= (νx)((νy)xy.yw.yz | x(y).y(h).y(h))

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-184-320.jpg)

![Some examples(0) - Sending channels

P ::= (νy)xy.yw.yz

Q ::= x(y).y(h).y(h)

R ::= (νx)((νy)xy.yw.yz | x(y).y(h).y(h))

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-185-320.jpg)

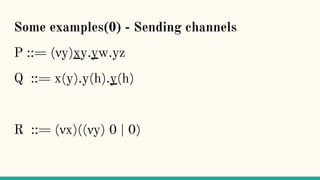

![Some examples(0) - Sending channels

P ::= (νy)xy.yw.yz

Q ::= x(y).y(h).y(h)

R ::= (νx)((νy)yw.yz | y(h).y(h))

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-186-320.jpg)

![Some examples(0) - Sending channels

P ::= (νy)xy.yw.yz

Q ::= x(y).y(h).y(h)

R ::= (νx)((νy)yw.yz | y(h).y(h))

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-187-320.jpg)

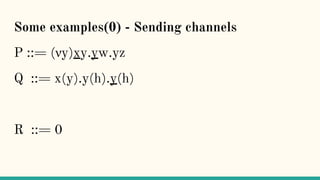

![Some examples(0) - Sending channels

P ::= (νy)xy.yw.yz

Q ::= x(y).y(h).y(h)

R ::= (νx)((νy)yz | y(h))

xy.P | x(z).Q → P | [y/z]Q communication](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-188-320.jpg)

![Two processes P and Q are bisimilar if ...

“Two processes P and Q are bisimilar if every

action of one can be matched by a corresponding

action of the other to reach bisimilar state” [1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-215-320.jpg)

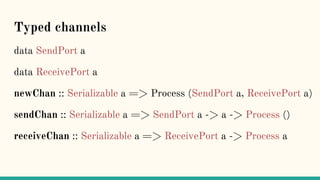

![Implementation issue...

“This seems quite natural.(...).But there’s a big problem here.

ReceivePorts are not Serializable, which prevents us passing

the ReceivePort r1 to the spawned process. GHC will reject the

program with a type error.” [8]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-225-320.jpg)

![Implementation issue...

“Why are ReceivePorts not Serializable? If you think about it a

bit, this makes a lot of sense. If a process were allowed to send

a ReceivePort somewhere else, the implementation would have

to deal with two things: routing messages to the correct desti‐

nation when a ReceivePort has been forwarded (possibly

multiple times), and routing messages to multiple destinations,

because sending a ReceivePort would create a new copy.” [8]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-226-320.jpg)

![Implementation issue...

“This would introduce a vast amount of complexity to the

implementation, and it is not at all clear that it is a good feature

to allow. So the remote framework explicitly disallows it,

which fortunately can be done using Haskell’s type system.”

[8]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-227-320.jpg)

![ρ-calculus

“The π-calculus is not a closed theory, but rather

a theory dependent upon some theory of names.

(...) names may be tcp/ip ports or urls or object

references, etc. But, foundationally, one might ask

if there is a closed theory of processes, i.e. one in

which the theory of names arises from and is

wholly determined by the theory of processes.” [7]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-241-320.jpg)

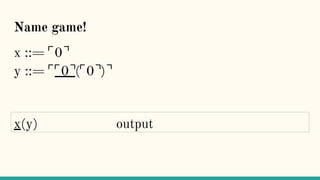

![Quoting

“Here we present a theory of an asynchronous

message-passing calculus built on a notion of

quoting. Names are quoted processes, and as such

represent the code of a process.(...) Name-passing,

then becomes a way of passing the code of a

process as a message.” [7]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-242-320.jpg)

![x⦉P⦊

“Process P will be packaged up as its code, ⌜P⌝,

and ultimately made available as an output at the

port x” [7]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-247-320.jpg)

![x⦉P⦊

“Process P will be packaged up as its code, ⌜P⌝,

and ultimately made available as an output at the

port x” [7]

“The lift operator turns out to play a role

analogous to (νx)”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-248-320.jpg)

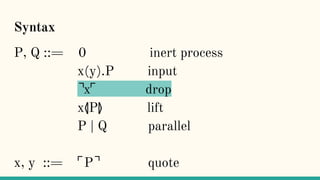

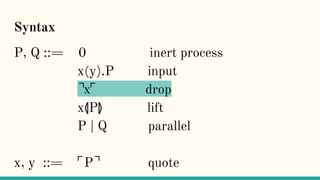

![⌝x⌜

“The ⌝x⌜ operator (...) eventually extracts the

process from a name. We say ‘eventually’ because

this extraction only happens when quoted process

is substituted into this expression.” [7]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-251-320.jpg)

![⌝x⌜

“A consequence of this behaviour is that the ⌝x⌜ is

inert, except under an input prefix” [7]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-252-320.jpg)

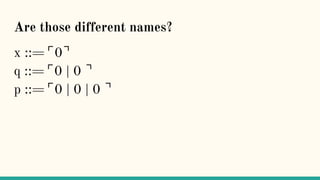

![Are those different names?

“This question leads to several intriguing and

apparently fundamental questions. Firstly, if

names have structure, what is a reasonable notion

of equality on names? How much computation, and

of what kind, should go into ascertaining equality

on names?” [7]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingdistributedcalculiinhaskell-180304222304/85/Understanding-distributed-calculi-in-Haskell-269-320.jpg)