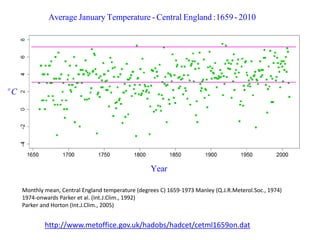

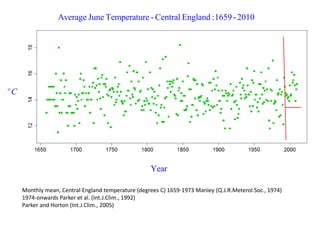

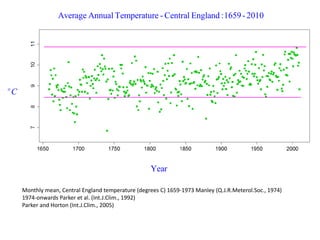

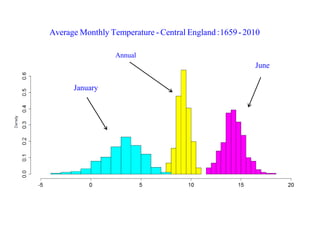

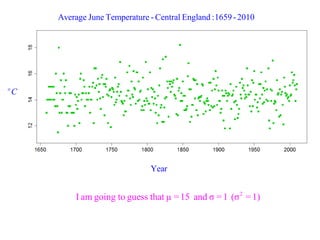

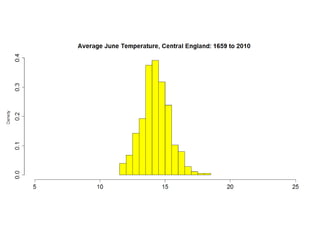

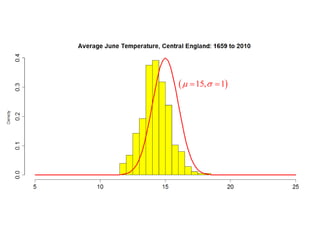

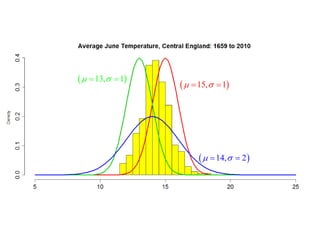

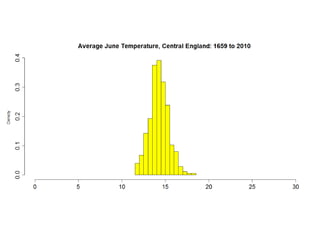

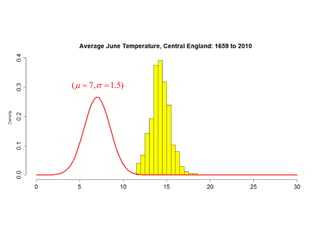

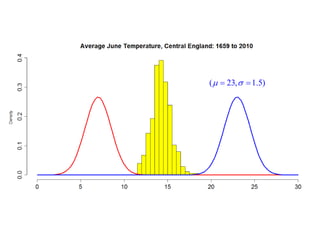

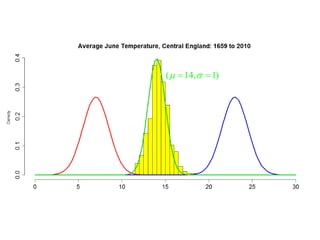

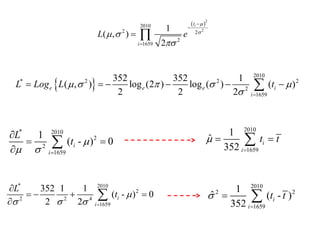

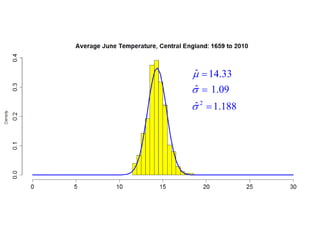

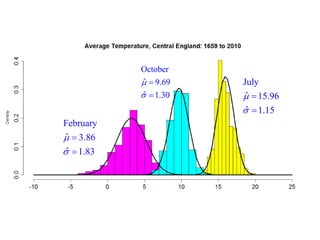

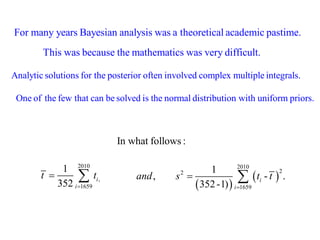

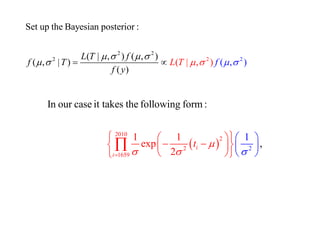

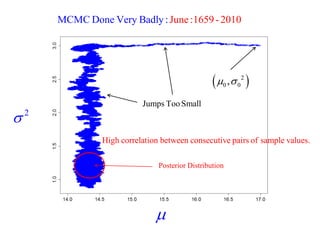

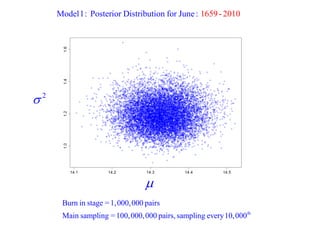

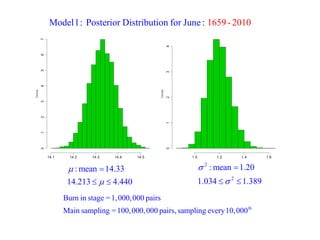

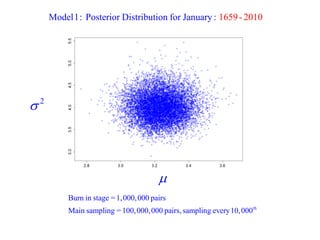

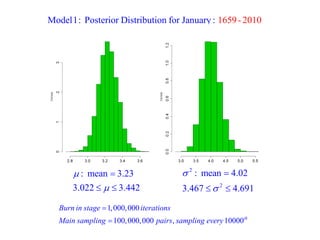

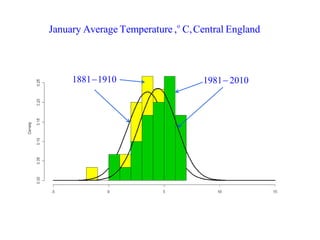

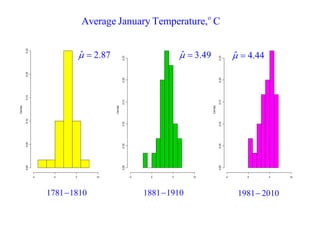

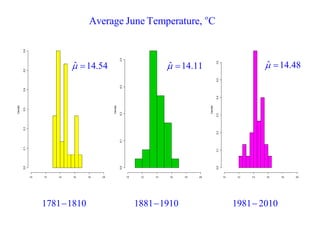

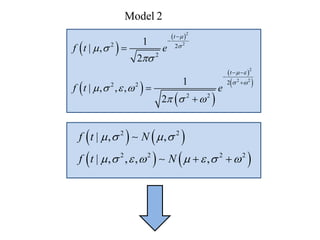

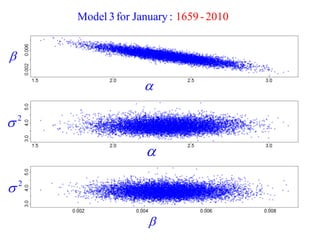

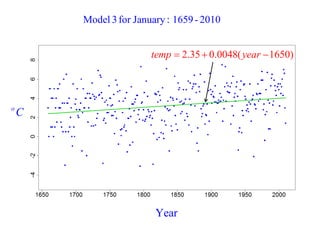

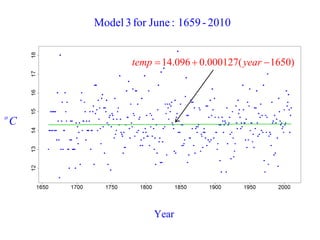

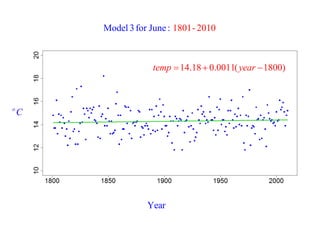

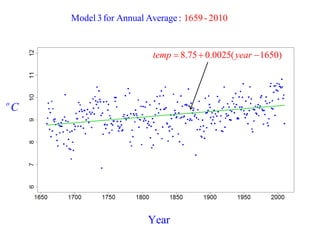

This document summarizes Peter Chapman's presentation on Bayesian inference to the Wokingham U3A Maths Group. It provides biographical details on Peter Chapman, including his educational and professional background. It then explains that the motivation for the presentation was to share his new learning about Bayesian methods and the software R with the group, after taking on a contract requiring him to use these. The presentation uses temperature data from Central England between 1659-2010 to illustrate Bayesian methodology, but is not about climate change specifically.