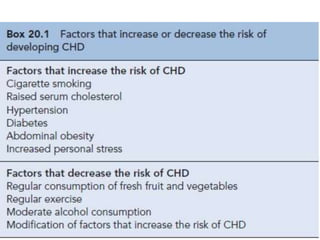

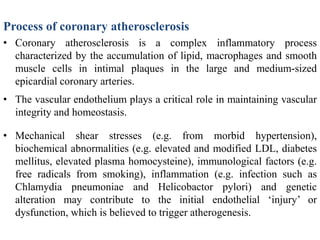

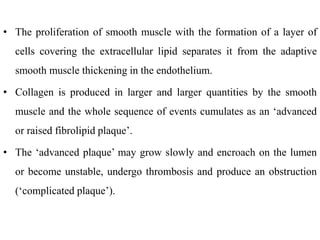

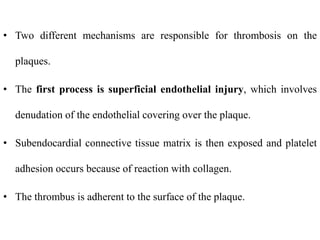

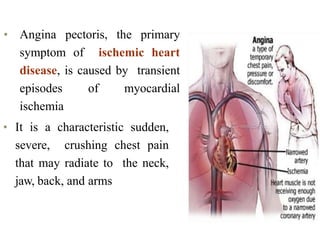

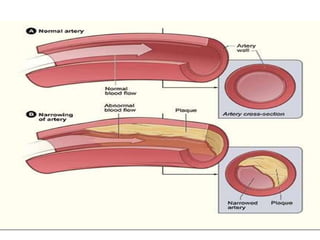

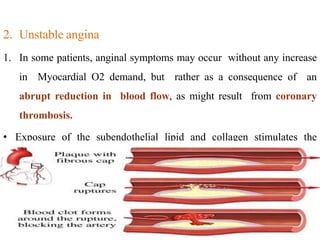

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a condition characterized by impaired blood supply to the heart due to factors like atheroma and thrombosis, leading to myocardial ischemia and potential heart muscle damage. Epidemiological data indicate that CHD is a leading cause of death, particularly in developed countries, with risk factors including hypertension, smoking, diabetes, and psychological stress. The disease presents in various forms, including stable and unstable angina, and its underlying pathology involves progressive atherosclerosis and potential plaque rupture, necessitating clinical attention and management strategies.

![• Ischemic heart disease (IHD) is defined as a lack of oxygen and

decreased or no blood flow to the myocardium resulting from

coronary artery narrowing or obstruction.

• IHD may present as an acute coronary syndrome (ACS, which

includes unstable angina and non–ST-segment elevation or ST-

segment elevation myocardial infarction [MI]), chronic stable

exertional angina, ischemia without symptoms, or ischemia due to

coronary artery vasospasm (variant or Prinzmetal angina).

• The primary clinical manifestation of CHD is chest pain.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3anginapectoris-211001170802/85/3-angina-pectoris-30-320.jpg)

![• Pharmacokinetic characteristics common to nitrates include a large

first pass effect of hepatic metabolism, short to very short half-lives

(except for isosorbide mononitrate [ISMN]), large volumes of

distribution, high clearance rates, and large interindividual variations

in plasma or blood concentrations.

• The half-life of nitroglycerin is 1 to 5 minutes regardless of the route,

hence the potential advantage of sustained-release and transdermal

products.

• Isosorbide dinitrate (ISDN) is metabolized to ISMN.

• ISMN has a half-life of about 5 hours and may be given once or twice

daily, depending on the product chosen.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3anginapectoris-211001170802/85/3-angina-pectoris-73-320.jpg)