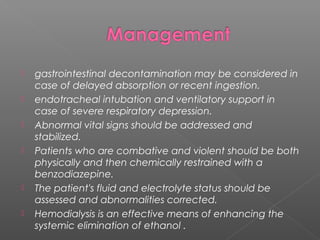

This document discusses the toxicity of ethanol. It is a colorless, volatile liquid that readily diffuses through membranes and is metabolized in the liver. Chronic ethanol consumption can lead to malnutrition, oxidative stress, production of toxic metabolites like acetaldehyde, and increased risk of cancer. Clinical effects include inebriation, respiratory depression, hypothermia, and dysrhythmias. Blood tests can assess electrolyte abnormalities. Treatment involves stabilization, fluid/electrolyte correction, and occasionally hemodialysis. Ethanol metabolism can also cause hypoglycemia or alcoholic ketoacidosis in malnourished chronic drinkers.