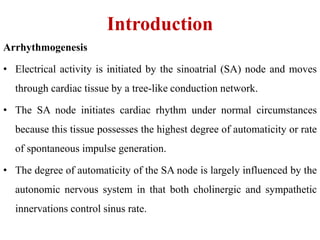

The document outlines the mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis within the cardiovascular system, detailing the roles of the sinoatrial node and conduction pathways. It describes different types of arrhythmias stemming from abnormalities in impulse formation and propagation, including triggered activity and re-entry. The pathophysiology of various arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia, is also explained along with their associated risks and potential treatments.

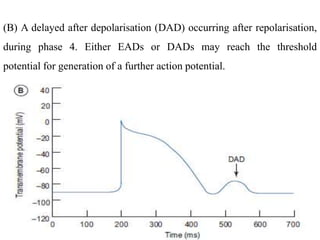

![• It occurs most commonly in acute myocardial infarction (MI); other

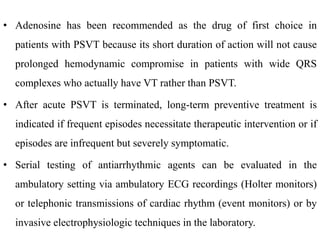

causes are severe electrolyte abnormalities (e.g., hypokalemia),

hypoxemia, and digitalis toxicity.

• The chronic recurrent form is almost always associated with

underlying organic heart disease (e.g., idiopathic dilated

cardiomyopathy or remote MI with left ventricular [LV] aneurysm).

• Sustained VT is that which requires therapeutic intervention to restore

a stable rhythm or that lasts a relatively long time (usually longer than

30 seconds).

• Non sustained VT self-terminates after a brief duration (usually less

than 30 seconds).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/6barrhythmia-211001171240/85/6b-arrhythmia-36-320.jpg)

![• Incessant VT refers to VT occurring more frequently than sinus

rhythm, so that VT becomes the dominant rhythm.

• Monomorphic VT has a consistent QRS configuration, whereas

polymorphic VT has varying QRS complexes.

• Torsade de pointes (TdP) is a polymorphic VT in which the QRS

complexes appear to undulate around a central axis.

3. Ventricular Proarrhythmia

• Proarrhythmia refers to development of a significant new arrhythmia

(such as VT, ventricular fibrillation [VF], or TdP) or worsening of an

existing arrhythmia.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/6barrhythmia-211001171240/85/6b-arrhythmia-37-320.jpg)

![4. Ventricular Fibrillation

• VF is electrical anarchy of the ventricle resulting in no cardiac output

and cardiovascular collapse.

• Sudden cardiac death occurs most commonly in patients with

ischemic heart disease and primary myocardial disease associated

with LV dysfunction.

• VF associated with acute MI may be classified as either

• (1) primary (an uncomplicated MI not associated with heart failure

[HF]) or (2) secondary or complicated (an MI complicated by HF).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/6barrhythmia-211001171240/85/6b-arrhythmia-39-320.jpg)

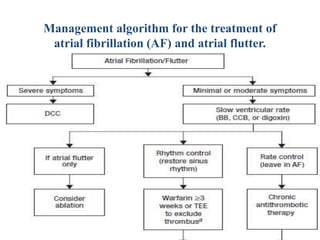

![• If sinus rhythm is to be restored, anticoagulation should be initiated

prior to cardioversion because return of atrial contraction increases

risk of thromboembolism.

• Patients with AF for longer than 48 hours or an unknown duration

should receive warfarin (target international normalized ratio [INR] 2

to 3) for at least 3 weeks prior to cardioversion and continuing for at

least 4 weeks after effective cardioversion and return of normal sinus

rhythm.

• Patients with AF less than 48 hours in duration do not requir warfarin,

but it is recommended that these patients receive either IV

unfractionated heparin or a low-molecular-weight heparin

(subcutaneously at treatment doses) at presentation prior to

cardioversion.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/6barrhythmia-211001171240/85/6b-arrhythmia-69-320.jpg)

![a) If AF <48 hours, anticoagulation prior to cardioversion is

unnecessary; may consider transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) if

patient has risk factors for stroke.

b) Ablation may be considered for patients who fail or do not tolerate

on antiarrhythmic drug (AAD).

c) Chronic antithrombotic therapy should be considered

in all patients with AF and risk factors for stroke regardless of

whether or not they remain in sinus rhythm. (BB, β-blocker; CCB,

calcium channel blocker [i.e., verapamil or diltiazem]; DCC, direct-

current cardioversion.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/6barrhythmia-211001171240/85/6b-arrhythmia-74-320.jpg)