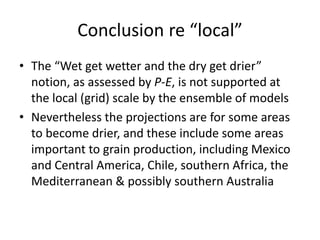

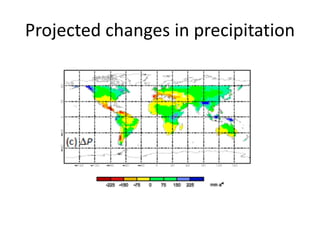

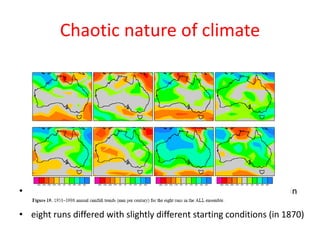

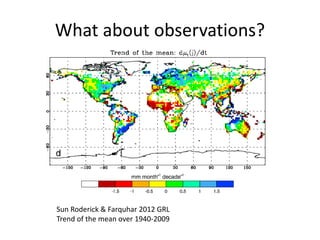

The document discusses the impact of climate change on wheat production, focusing on changes in precipitation and evaporation patterns due to rising temperatures. It highlights the variability of predicted climate outcomes at local scales, contrasting the 'wet get wetter and dry get drier' theory with observed trends. It emphasizes the need for further research on water-use efficiency and the effects of elevated CO2 levels on plant growth and yields while considering the chaotic nature of climate systems.

![Effects of [CO2] and T on growth &

yield

• To what extent can we use responses to today’s

variations in temperature to learn about future

changes in T?

• Effects of T on assimilation rate are different at

different [CO2]

• In the short term there are interfering

correlations with less rainfall

• Effects on sterility or abortion-poorly understood

(see Poster 132)

• Photothermal quotient](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-140408141608-phpapp02/85/Wheat-and-climate-change-20-320.jpg)

![How does CO2 concentration affect the

water requirements of plant growth?

• At the leaf level doubling the [CO2] is

effectively like almost doubling the rainfall. cf

Wong, Cowan & Farquhar Nature 1979

• So when the [CO2] was only half its present

value, say 20,000 years ago, the rainfall would

only have been about half as effective as that

rainfall would be today.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-140408141608-phpapp02/85/Wheat-and-climate-change-21-320.jpg)

![Impact of CO2 fertilization on maximum foliage

cover across the globe’s warm, arid environments

Randall J. Donohue, Michael L. Roderick, Tim R.

McVicar, and Graham D. Farquhar

GRL 2013

From 1982 to 2010 [CO2] increased 14% and the

responsiveness of foliage cover to precipitation increased

11% in the driest regions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-140408141608-phpapp02/85/Wheat-and-climate-change-23-320.jpg)

![Four Summary Messages

3. Research on water-use efficiency (which should

increase in rain-fed environments under

increasing [CO2]) and drought tolerance, for

present-day problems, will be vital for future

climates, particularly in the context of increased

demand for water, just as will research on

improvement of yield potential.

4. There could be surprises and an understanding

of [CO2] effects on e.g. photosynthesis,

flowering and plant water relations in an

ecological context would be insurance.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-140408141608-phpapp02/85/Wheat-and-climate-change-25-320.jpg)