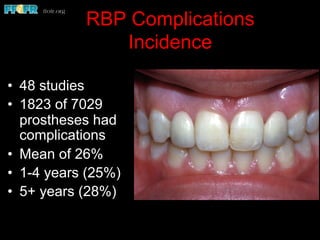

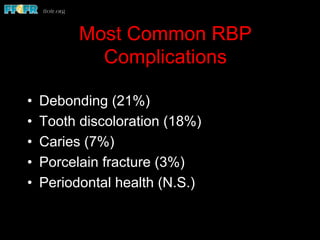

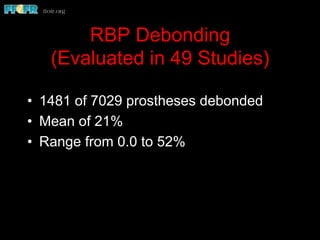

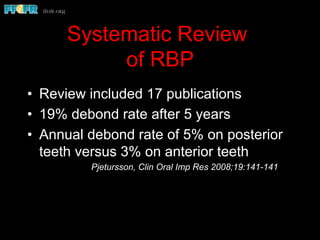

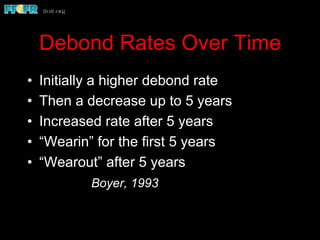

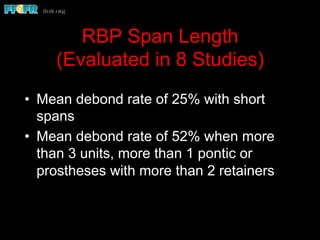

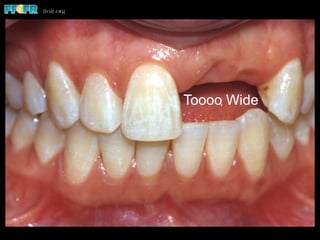

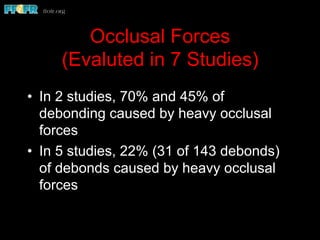

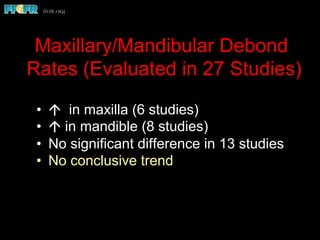

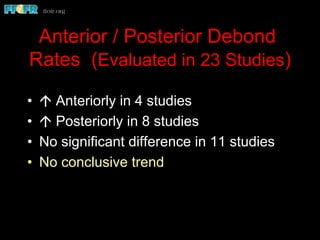

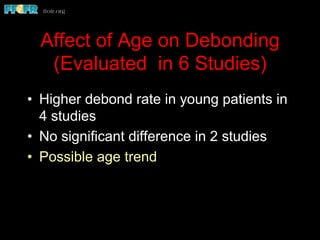

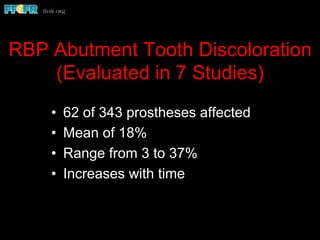

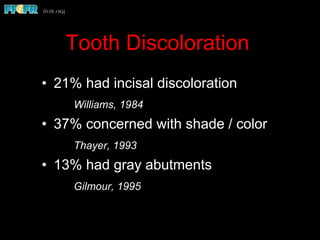

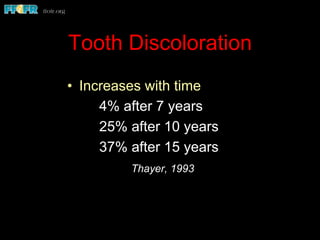

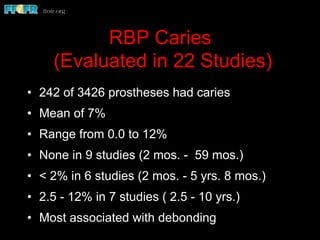

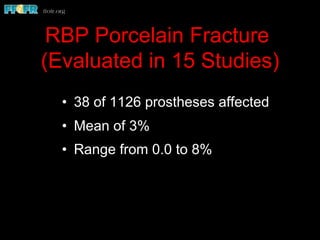

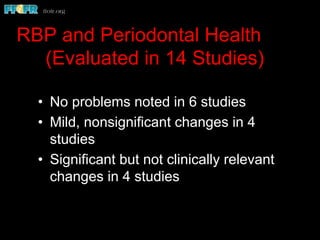

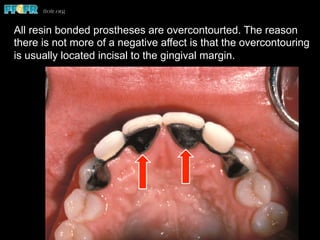

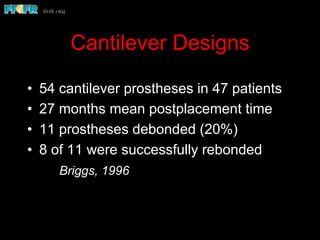

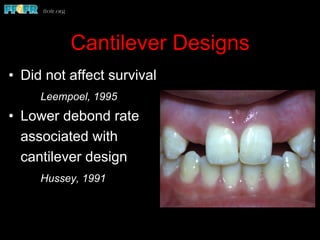

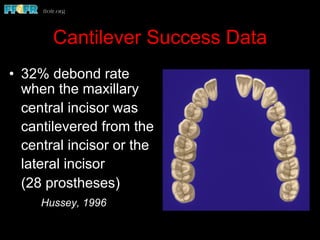

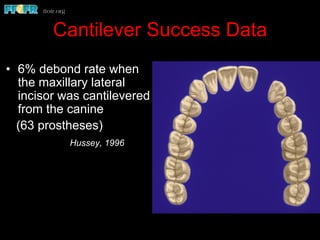

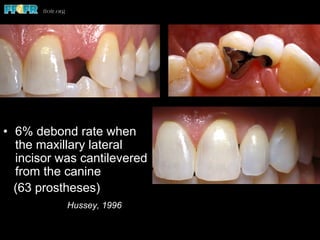

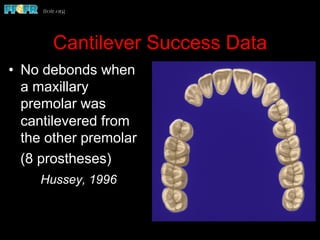

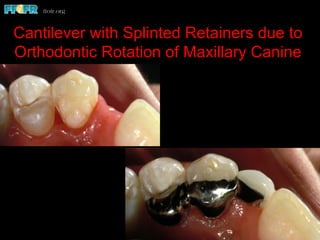

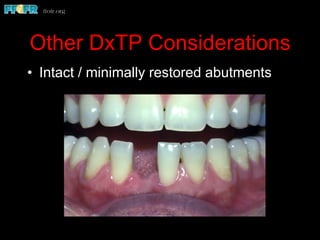

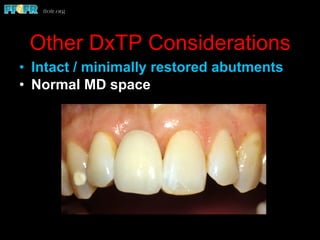

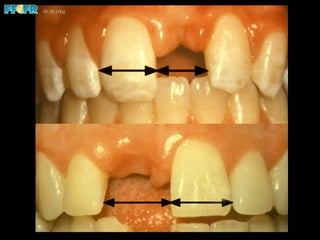

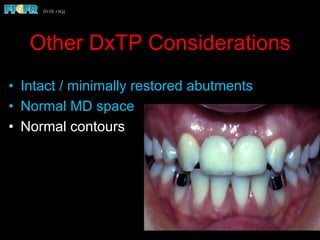

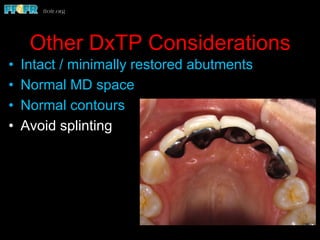

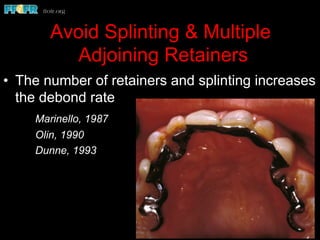

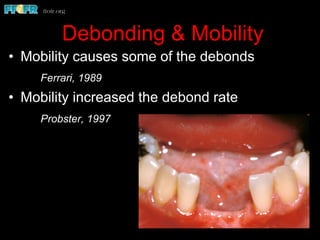

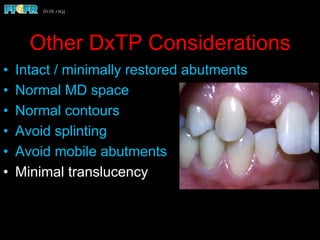

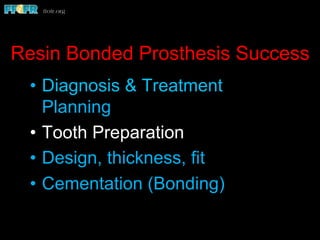

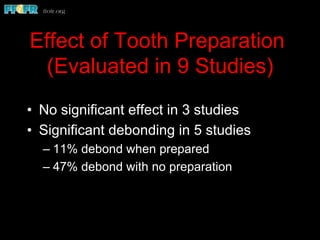

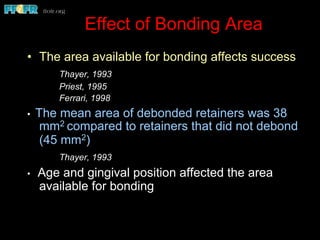

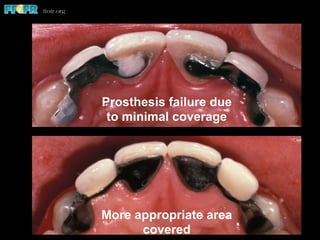

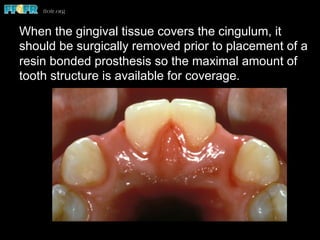

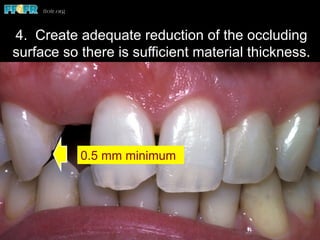

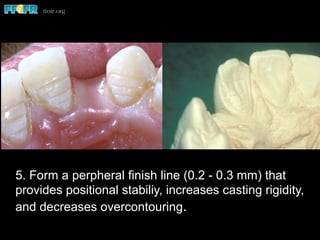

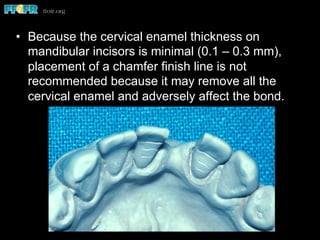

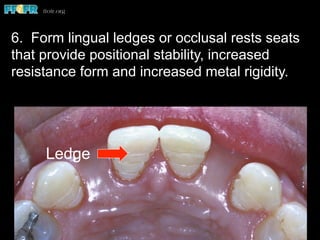

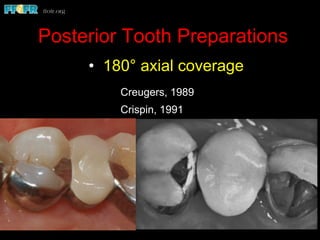

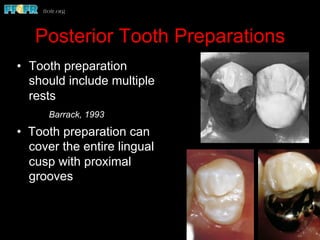

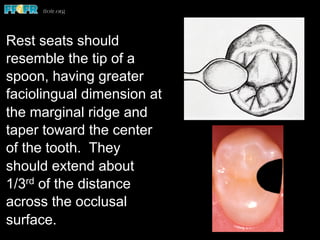

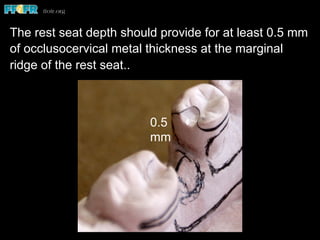

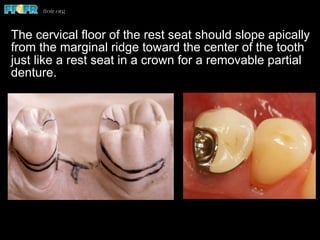

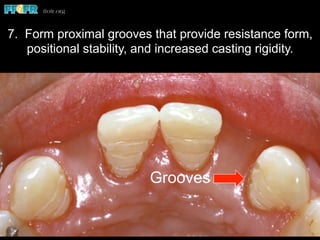

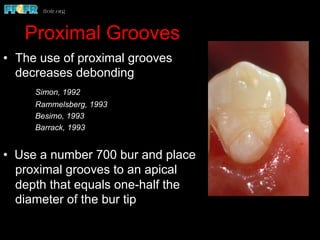

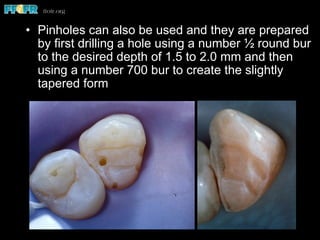

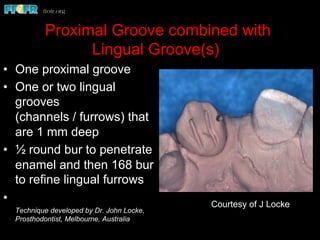

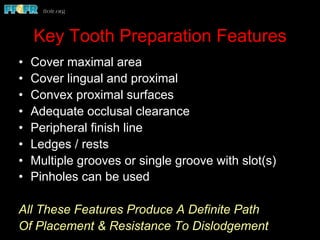

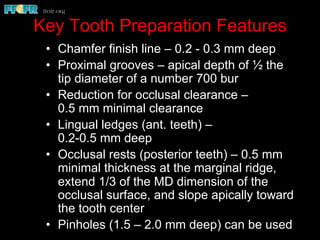

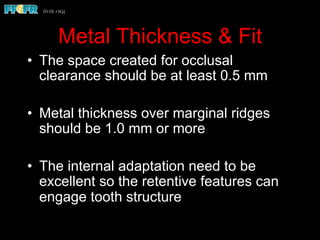

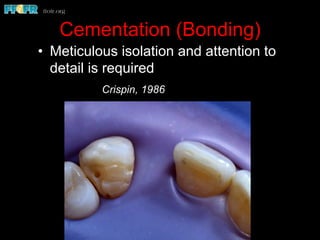

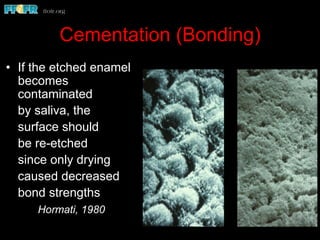

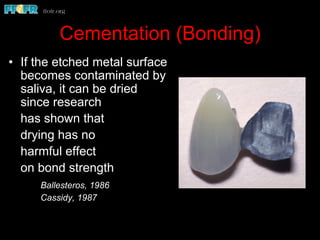

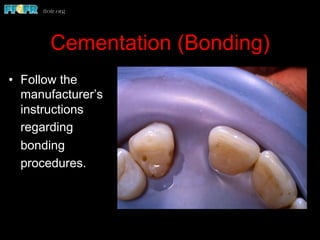

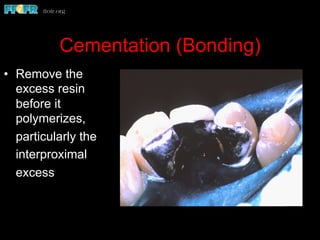

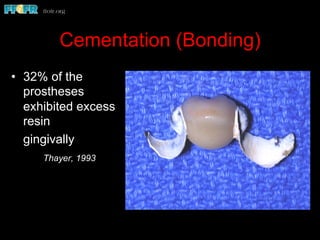

This document summarizes research on the success rates and complications of resin bonded prostheses (RBPs). It finds that on average, 26% of RBPs experience complications within 4 years, increasing to 28% after 5 years, with debonding being the most common at 21%. Debonding rates are higher for posterior teeth, longer spans, and cantilever designs. Tooth preparation techniques like covering lingual and proximal surfaces, adding proximal grooves or pinholes, and occlusal rests can reduce debonding. Maintaining a minimum of 0.5mm occlusal clearance and 1mm metal thickness also impacts success. Proper diagnosis, treatment planning and cementation techniques are keys to optimizing longevity