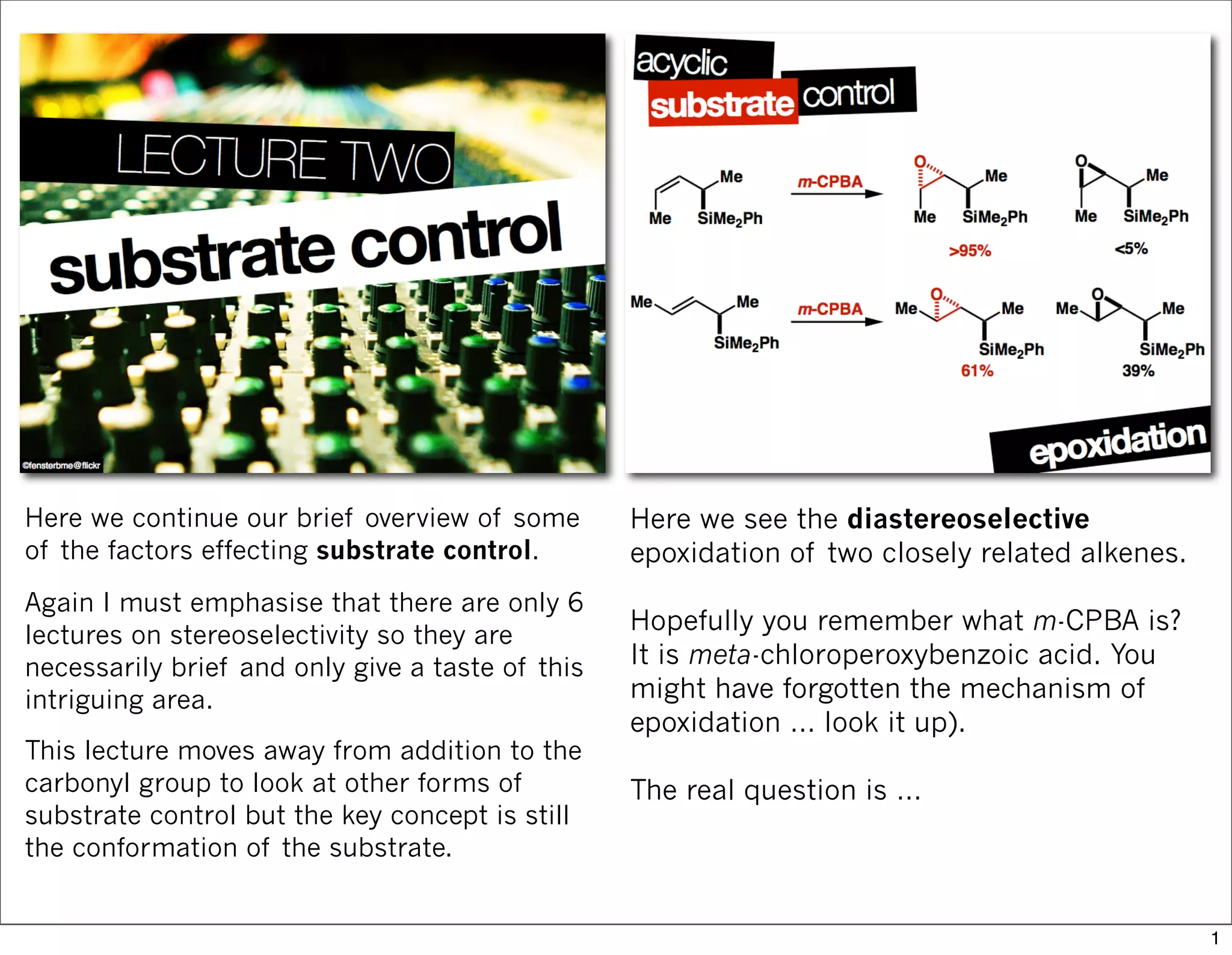

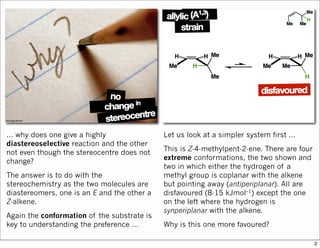

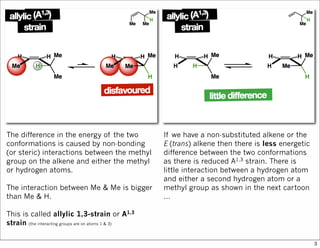

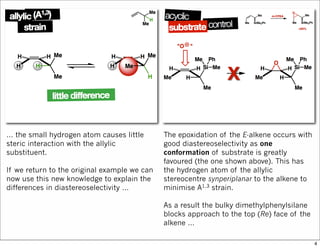

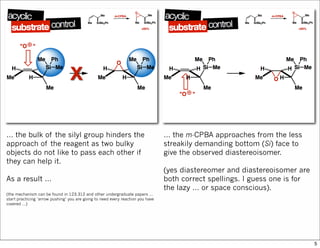

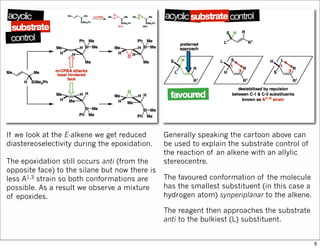

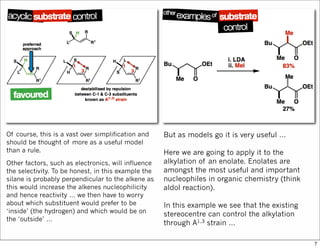

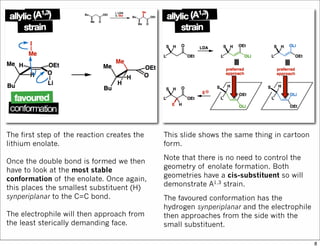

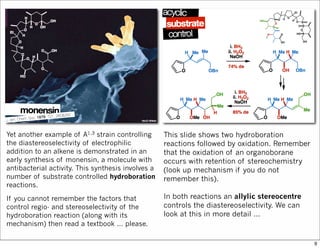

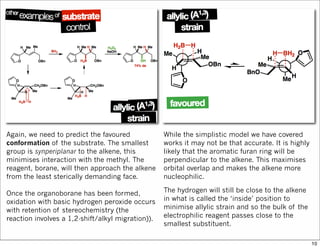

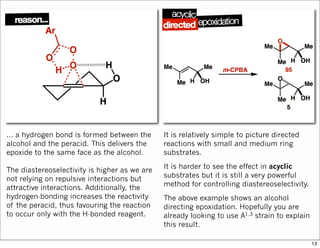

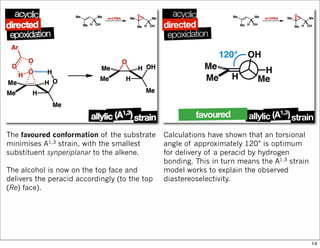

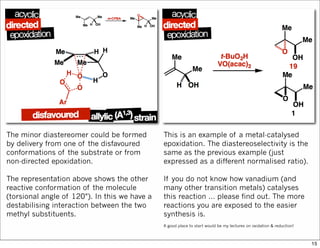

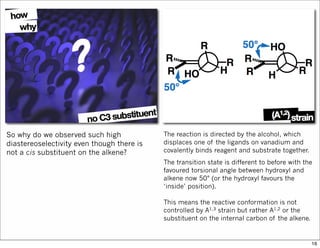

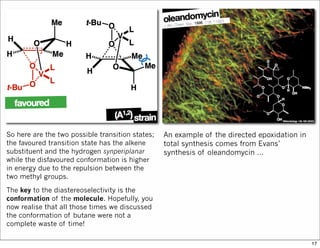

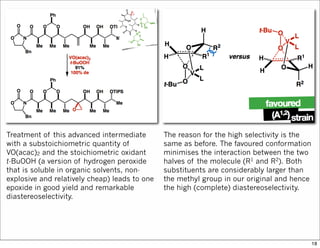

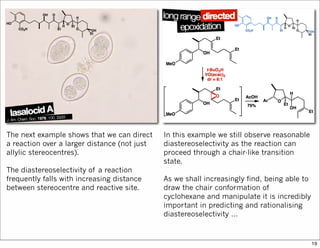

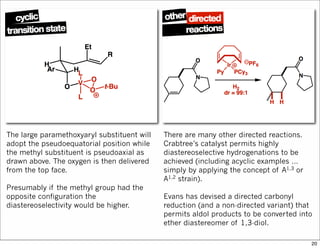

1) The document discusses various methods of substrate control in organic reactions, focusing on how substrate conformation can influence diastereoselectivity. Allylic 1,3-strain (A1,3 strain), where substituents on the first and third carbons interact sterically, is a key concept.

2) Reactions like epoxidation and hydroboration are often highly diastereoselective when the substrate adopts a conformation that positions the smallest substituent syn to the reactive double bond to minimize A1,3 strain. The reagent then approaches from the least hindered face.

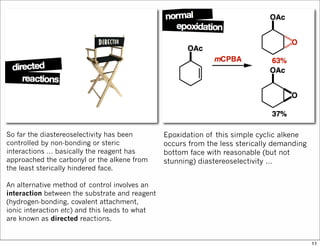

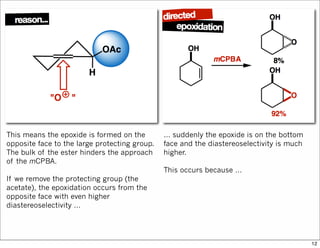

3) Directed reactions use hydrogen bonding or coordination to deliver the reagent to one