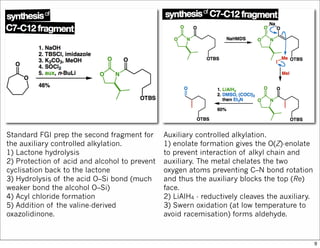

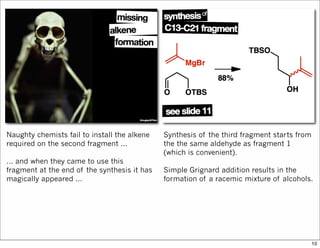

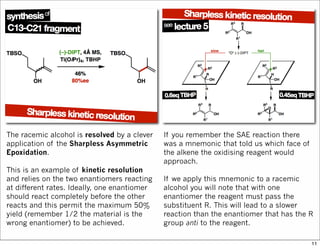

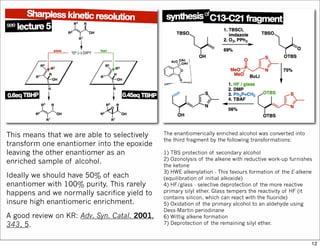

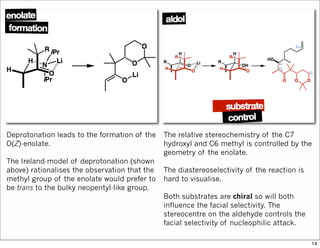

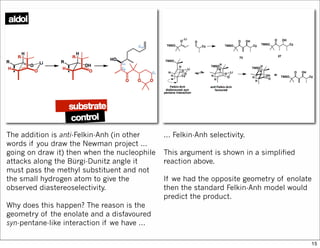

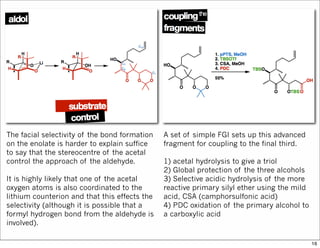

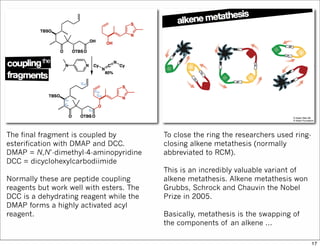

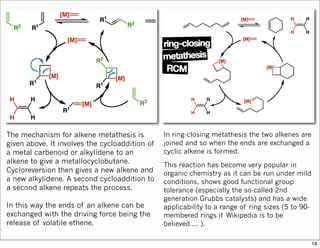

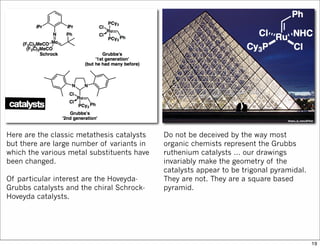

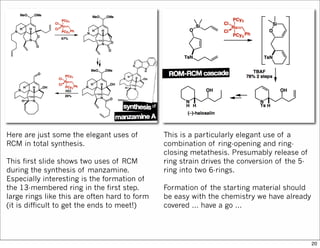

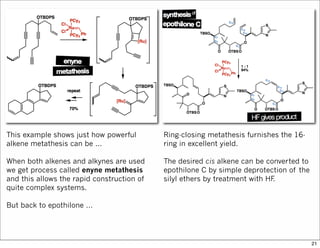

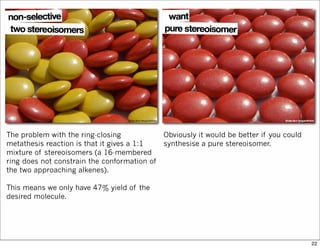

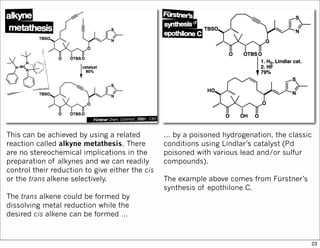

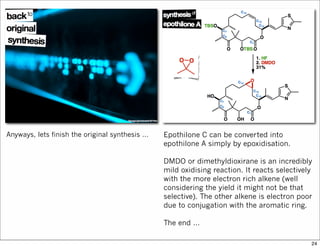

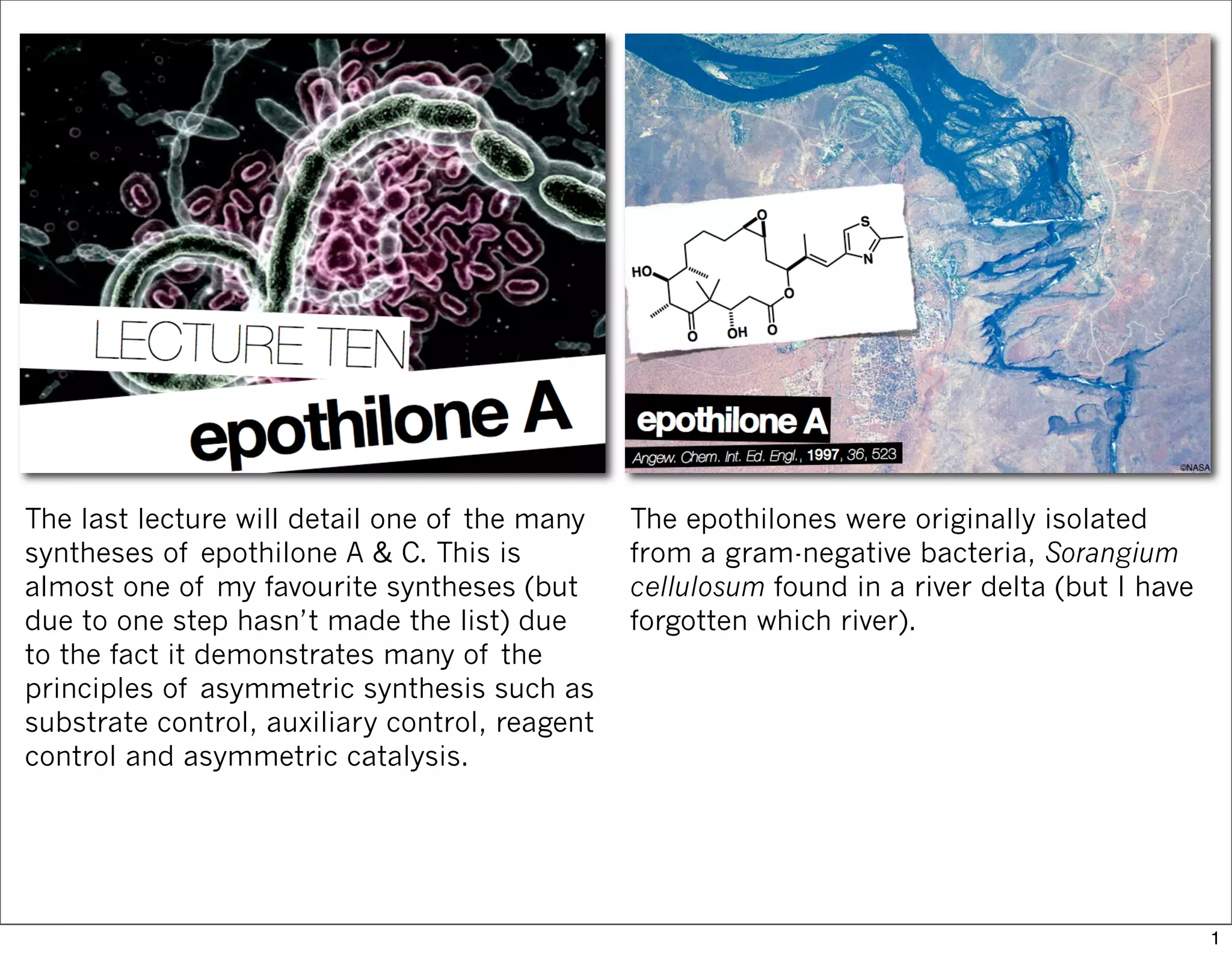

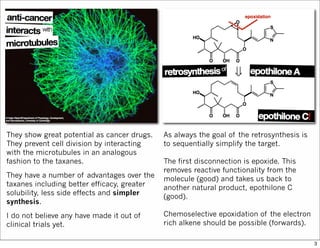

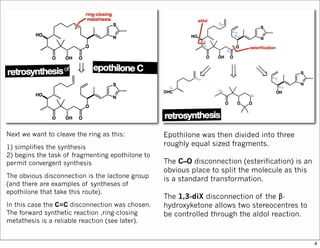

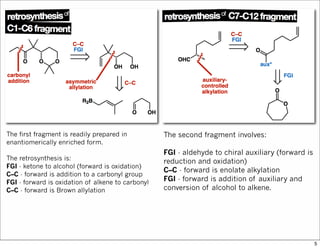

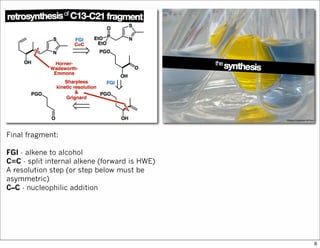

The document outlines a synthesis of epothilone A and C, emphasizing the principles of asymmetric synthesis and their potential as cancer drugs. It details the retrosynthetic analysis, fragmentation, and various synthetic steps involved, including reactive transformations and selective reactions. The concluding discussion highlights the use of ring-closing metathesis and the challenges related to stereochemistry in achieving desired yields.

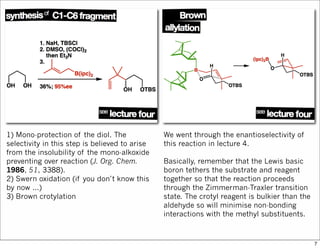

![1) Acetal formation - the reaction

conditions are sufficiently acidic to

promote deprotection of the primary silyl

ether (TBS = tert-butyldimethylsilyl).

2) Oxidative cleavage of the alkene. This

employs a substoichiometric quantity of

OsO4 and stoichiometric NaIO4. The OsO4

mediates dihydroxylation while the NaIO4

re-oxidises the osmium and cleaves the

diol. This is analogous to ozonolysis.

1) Addition of a Grignard reagent. We do

not care if the reaction is diastereoselective

or not because ...

2) Oxidises the alcohol to the ketone. TPAP

(tetrapropylammonium perruthenate [Pr4N]

[RuO4]) is a catalytic oxidant while NMO (N-

methylmorpholine N-oxide) is the

stoichiometric oxidant (it oxidises the

ruthenium).

That finishes the first fragment.

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/123713ablecture10-161118000039/85/123713AB-lecture10-8-320.jpg)