This document provides an overview of wildlife and protected area management topics covered in the PWM 703 course. It includes 7 units that cover introductions to biodiversity concepts and status, policies and legislation, wildlife and habitat management, monitoring biodiversity, and protected area planning and management. The document was compiled by Namrata Khatri and Abiral Acharya for their Masters in Forestry program at IOF, TU in Nepal.

![Compiled By Namrata Khatri and Abiral Acharya

73

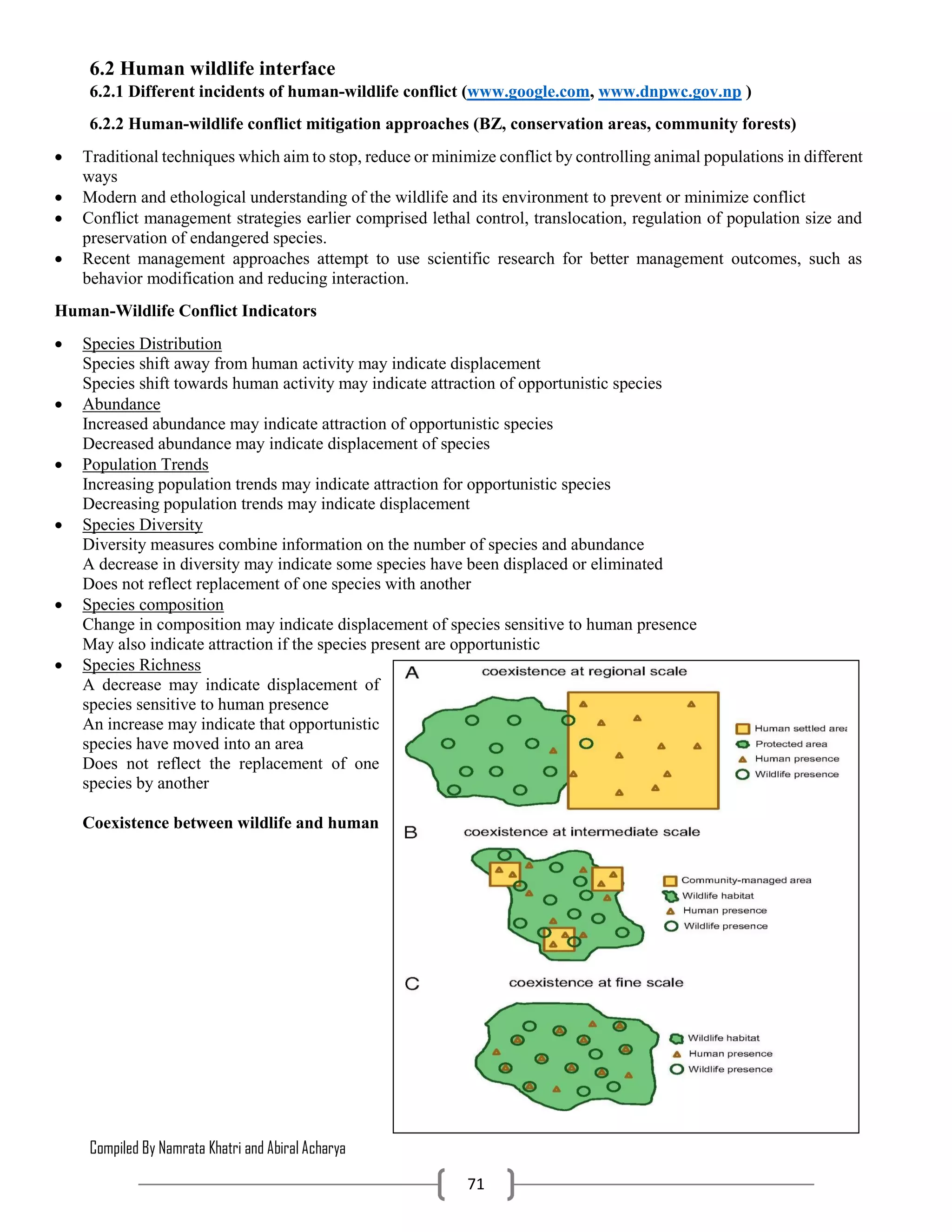

to protected areas, on which land is partially restricted to give an added layer of protection area itself while

providing valued benefits to neighboring rural communities‖

where restrictions are placed upon resource use or special development measures are undertaken to enhance

conservation value of the area‖ .

nature, ignorance to traditional use rights as well as social and economic interests of local people and lack of local

involvement in decision making activities (Paudel, 2002).

protected area as well as to bridge the gap between the immediate needs of local people and the long-term objective

of protected area system (Aryal, 2008).

political, economic, social, cultural, ecological and intrinsic value of resources.

Major project interventions- short term, mid- term and long term

• Handing over and management of buffer zone community forests

• Capacity building linking to income generation and conservation efforts

• HWC mitigating tools and mechanisms such as Machans, electric fences, trenches, improved corals in the

mountains, non -edible plants introduction etc

• Community capital mobilization

• Compensation of 30-50% to the buffer zone by the government

• Conservation awareness and orientation

• Community based antipoaching teams formation

• Infrastructure built

• Ecotourism benefits

• Habitat management for example water holes, grass land management

• Relief distribution to the wildlife victims

• Initiate community participation and ownership of management

• Adoption of Human Wildlife Conflict mitigation policies and compensation policesRahat Nirdesika 069

10 2.doc

• Problem Animal Control units (PAC units)

• Record keeping and database

• Problem mitigation strategies- dfgj jGohGt' åGb Go"gLs/0f, 3fOt] tyf ;d:ofu|:t jGohGt'sf] p4f/ ;DaGwL sfo{x? ug]{ .

• Problem Animal Control units (PAC units)

• Species status surveys

• Landuse planning

• Long term planning….

• Capacity building

• Scholarship to the victims kids

Buffer zone HWC mitigation commitments](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wildlifeandpamgmt-iofpokhara-200202091021/75/Wildlife-and-Protected-Area-Management-74-2048.jpg)